A significant initiative by Greece to approve and submit its Maritime Spatial Plan (MSP) to the EU sets in motion the final charting, via maps, of the differing positions of Greece and Turkey on the delimitation of their maritime zones. Turkey is reportedly preparing to respond with its own map, which will reflect its known pursuits and claims to date.

Turkey’s map showcases unilateral claims in violation of international law.

The MSP is an important step in exercising Greece’s sovereign rights. However, it will be judged in practice, once its implementation begins in the field — especially in areas where Greece already holds established rights or seeks to exercise them, but Turkey openly disputes them.

After considerable delays, which even led to a condemnation by the European Court of Justice, the Greek government finally decided to approve the MSP. Beyond the ECJ’s deadline of April 27, there was a serious risk that, following the postponement of the Cyprus-Crete cable project, Greece might appear reluctant to assert its sovereign rights or even publicly define its maritime zone boundaries due to fear of Turkey.

A Significant Move

To regard this decision as merely a communication ploy to deflect concerns over the delayed undersea cable project between Crete and Cyprus would be unfair. This is a vital first step in asserting Greece’s sovereign rights. For the first time, Greece’s furthest maritime claims are recorded in an official public document, based on the Law of the Sea — now bearing a European endorsement through its submission to the EU.

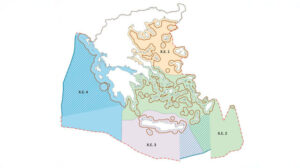

The government clarifies from the outset that the MSP does not proclaim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), nor does it grant sovereignty or sovereign rights. It reflects the currently existing maritime zones (e.g., EEZ based on agreements with Italy and Egypt), 6-nautical-mile territorial waters (with the reservation for future extension to 12 n.m., as allowed by the Law of the Sea), and the entire potential EEZ as defined by Law 4001/2011.

Under this law, in the absence of a delimitation agreement with neighboring or opposite states, Greece considers the median line, as calculated by Greece, to be the outer limit of its EEZ. Based on this, Greece has delineated plots south and southwest of Crete, which have even been granted to foreign companies for hydrocarbon exploration.

Missing Maritime Extension?

There are, however, questions about the absence of the potential 12-n.m. territorial waters in the map — as had appeared in the unofficial working map published by the European Commission, which triggered intense reactions from Turkey.

Since blocking Greece from expanding its territorial waters to 12 n.m. is a central Turkish goal, depicting the current 6 n.m. likely served as a calming gesture.

The map also reflects Greece’s concessions in the EEZ agreement with Egypt — deemed necessary at the time as a formal response to the Turkey-Libya memorandum.

Turkey’s Response

Turkey’s official response was couched in diplomatic terms, stating that Greece’s unilateral actions and claims violate Turkish maritime jurisdiction in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, and “have no legal consequence for Turkey.” Turkey warned it would submit its own MSP to UNESCO and relevant UN bodies, presenting itself as moderate. It emphasized that issues should be resolved via international law, equality, and good neighborliness — referring to the Athens Declaration.

Clearly, with two conflicting and overlapping MSPs in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, their credibility and viability will ultimately be tested on the ground.

The MSP itself does not automatically authorize specific activities, but provides the broader legal and regulatory framework. While Turkey’s current reaction is diplomatic, when it comes to implementing actual projects, each country will need to defend the sovereign rights asserted via their respective MSPs.

Cable Projects and Sea Parks

Among the MSP’s regulated activities is the placement of pipelines and cables, keeping the Cyprus–Crete power link a hot issue and a point of friction. Foreign Minister Giorgos Gerapetritis referred again to “appropriate timing” due to the complexity of the project but insisted all projects will proceed. Still, postponement of field exploration cannot continue indefinitely — and will serve as one of the first real-world tests of the MSP.

Another challenge will be the creation of Marine Parks in the Aegean — a move the Greek government promised to complete by the end of 2024, despite strong Turkish opposition, especially as they include activities on islets Turkey considers “gray zones.”

By adhering to the Law of the Sea and benefiting from EU legal backing, Greece’s MSP carries more international legitimacy than the Turkish version — which is based on legal gymnastics and lacks global recognition, even if Turkey files it unilaterally with UNESCO, as suggested by Turkish media.

Greek Diplomacy and Future Challenges

In a TV interview, Foreign Minister Gerapetritis suggested that the MSP makes it clear that any opposition should be addressed through dialogue and international legal mechanisms — including potentially a joint application to the Hague Court.

However, these maps, even with the Turkish version pending, will not alter the known differences in Greek-Turkish relations. Turkey is pushing for comprehensive bilateral negotiations that include all its unilateral claims, starting with talks.

For Athens, formally stating its claims over the potential continental shelf was a prerequisite for taking further steps — including submitting these coordinates to the UN, and advancing actions like closing bays and drawing baselines for calculations. There’s also the plan for gradual extension of territorial waters to 12 n.m. south of Crete, as previously announced.

Political Sensitivities

This was a bold and difficult step for the government. Adoption of the MSP map may falsely imply — to the public as well — that these maritime zones are already secured, which is inaccurate. Zones like the EEZ must be declared and, more importantly, delimited — either through bilateral agreements or adjudication at The Hague.

The issue of granting full effect to Kastellorizo, which provides Greece a maritime link to Cyprus and blocks Turkey’s intended maritime border with Egypt, will be decided either through agreement or The Hague. But due to the principle of proportionality, Greece’s chances are not strong.

This creates additional political pressure and responsibility for any future government negotiating with Turkey — not just regarding Kastellorizo, but all disputed maritime zones around Greek islands.

Ankara’s Preparation

Turkey was aware of the Greek MSP approval in advance, thanks to ECJ deadlines. Just before Greece’s announcement, Turkish paper Milliyet leaked a draft Turkish MSP and map — not an official document, but a study from Ankara University’s National Center for Maritime Law Research (DEHUKAM). The institute clarified it’s an academic study and not the official position of the Turkish Republic. Only the Presidency can issue the official MSP.

However, Turkey’s quick use of the map indicates that this study may form the basis for its forthcoming official MSP, likely to be fast-tracked as a response to Greece.

The Turkish study follows Ankara’s maximalist claims: drawing the median line between mainland coasts and ignoring Greek islands, shifting the line to the middle of the Aegean. It fully embraces Turkey’s unilateral submission to the UN (March 18, 2020 — A/74/757), the “Blue Homeland” doctrine, the Turkey-Libya Memorandum, and the illegal EEZ deal with the unrecognized TRNC.

It also refers to the Bern Protocol — considered void by Greece — through which Turkey insists that Greece must refrain from any activity outside its 6 n.m. territorial waters, even in clearly potential Greek maritime zones.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions