A medieval parchment from a monastery in Egypt has yielded a surprising treasure. Hidden beneath Christian texts, scholars have discovered what seems to be part of the long-lost star catalogue of the astronomer Hipparchus — believed to be the earliest known attempt to map the entire sky.

Scholars have been searching for Hipparchus’s catalogue for centuries. James Evans, a historian of astronomy at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington, describes the find as “rare” and “remarkable”. The extract is published online this week in the Journal for the History of Astronomy1. Evans says it proves that Hipparchus, often considered the greatest astronomer of ancient Greece, really did map the heavens centuries before other known attempts. It also illuminates a crucial moment in the birth of science, when astronomers shifted from simply describing the patterns they saw in the sky to measuring and predicting them.

The manuscript came from the Greek Orthodox St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt, but most of its 146 leaves, or folios, are now owned by the Museum of the Bible in Washington DC. The pages contain the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a collection of Syriac texts written in the tenth or eleventh centuries. But the codex is a palimpsest: parchment that was scraped clean of older text by the scribe so that it could be reused.

The older writing was thought to contain further Christian texts and, in 2012, biblical scholar Peter Williams at the University of Cambridge, UK, asked his students to study the pages as a summer project. One of them, Jamie Klair, unexpectedly spotted a passage in Greek often attributed to the astronomer Eratosthenes. In 2017, the pages were re-analysed using state-of-the-art multispectral imaging. Researchers at the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library in Rolling Hills Estates, California, and the University of Rochester in New York took 42 photographs of each page in varying wavelengths of light, and used computer algorithms to search for combinations of frequencies that enhanced the hidden text.

Williams identified star coordinates in the text and proceeded to further analysis, in collaboration with science historian Victor Gieseberg of the French National Institute for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Emmanuel Xing of the Sorbonne University in Paris.

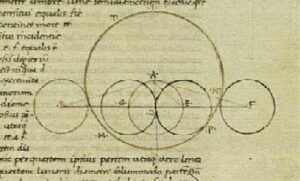

It was thus revealed that on at least one page of the parchment, precise coordinates were given for the stars at the four ends of the Corona Borealis constellation. Strong evidence has also been found that the source of these measurements was Hipparchus and that his calculations were made around 129 BC.

Until today, the only star catalogue that had survived from antiquity was that of the astronomer Ptolemy in Alexandria, Egypt in the 2nd century AD. His Almagest (or Mathematical Syntax) was one of the most influential scientific texts in history, presenting a geocentric mathematical model of the world that had been widely accepted for over 1,200 years. Ptolemy had, among other things, given the coordinates of more than 1,000 stars.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions