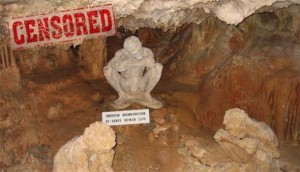

A shepherd stumbled across the Petralona skull in Chalkidiki, Northern Greece, thus kicking off one of Greece’s best-kept mysteries. The cave opening he discovered in 1959 led to a magnificent cave of stalactites, stalagmites and a human skull embedded in the wall as well as a huge number of fossils that appeared to belong to a pre-human species.

The skull, bones and fossils were given to the University of Thessaloniki in Greece for study, and the villagers who found them hoped that there would be research on the matter drawing the spotligh on Petralona and creating a museum. Instead, the story of the skull disappeared.

Dr. Aris Poulianos, a member of UNESCO’s IUAES (International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences) found the skull and began to research it a few years after it was found. Known as the ‘Petralona man’, the skull was estimated to be 700,000 years old. He ascertained that the skull belonged to the oldest human europeoid, that evolved separately in Europe and was not an ancestor of an African species of pre-humans.

Independent German researchers Breitinger and Sickenberg tried to dismiss the Greek doctor’s findings in 1964 by stating that the skull was only 50,000 years old and of African origin. Research in the prestigious US archeology magazine, however returned to Dr. Poulianos findings and believed that it may indeed have been 700,000 years old according to an analysis of the cave’s stratigraphy and the sediment in which the skull was independent. Later, they found isolated teeth and other pre-human skeletons in the cave that date back 800,000 years.

Research continued until 1983 before the government ordered excavations at the site to stop. Entrance was forbidden for all, including the original team. No reason was given and the case was taken to courts and access was allowed. Despite this, there have been battles by the Ministry of Culture to prevent research in the area and there is a group of academics that is concerned about the suppression of information.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions