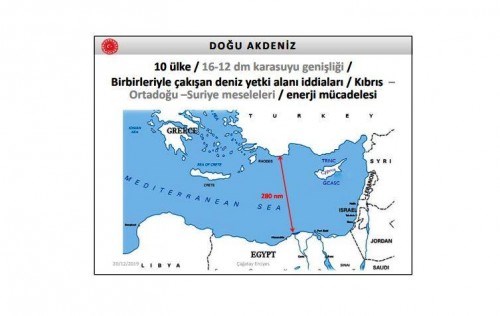

The recent naval incident in the Mediterranean between French and Turkish warships is another dramatic development in an already deteriorated situation involving a neo-Ottoman Turkey with growing geopolitical ambitions colliding with the core security interests of many European countries.

On 10 June, the merchant vessel Cirkin – sailing under the Tanzanian flag, escorted by Turkish warships and suspected of smuggling weapons into Libya in contravention of the UN Security Council Resolution 2473, imposing an arms embargo on all the protagonists in the Libyan war – was challenged by the French frigate Courbet, which was taking part in NATO’s Operation Sea Guardian, whose task is to work with the Mediterranean to maintain maritime situational awareness, as well as deter and counter terrorism. Earlier in the day, an unsuccessful challenge attempt on the Cirkin had been made by a Greek frigate. This frigate was part of the EU’s Operation Irini, whose purpose is to implement the UN-mandated arms embargo.

In reaction to the Courbet getting closer to the Cirkin, the Turkish warships flashed their fire-control radars with crews putting on bulletproof vests and standing behind their light weapons. Even by the standards of Cold War confrontations between Western navies and the then Soviet Navy’s so-called Mediterranean Eskadra, the Turkish Navy’s behaviour was extremely aggressive.

Immediately thereafter, France requested a NATO Council meeting to discuss the incident and asked for an official inquiry by the Alliance. Interestingly, whereas 10 NATO members supported France’s demand (Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and the UK), none of the Alliance’s eastern flank (Slovakia excepted) or Nordic members did.

The perspective of Turkey relenting on its longstanding opposition to approving NATO’s defence plans for Poland and the Baltic states may have played a role in those countries’ official silence, yet none of these considerations apply to the US’s astounding silence. It is notable, however, that all of NATO’s European Mediterranean countries (except Croatia and Albania) supported France’s request.

France also suspended its participation in Sea Guardian and asked for the Alliance to collectively adopt some measures, including:

- – An official reaffirmation by NATO of the respect of the embargo.

- – A clear rejection of the use of NATO call signs by Turkish ships if/when they do not comply with UNSCR 2473.

- – Reinforced cooperation between NATO and the EU in the Eastern Mediterranean.

- – The establishment of deconfliction procedures at sea.

Long-Term Implications

No one should underestimate the seriousness of the tactical standoff that occurred on 10 June, with its risks of escalation. But the growing strategic divide between NATO members that these events underline is even more concerning for the future of the Alliance.

The situation in 2020 can hardly be compared to the one of 1974, a year which saw Ankara invading the northern part of Cyprus and tensions with Greece spiraling dangerously. At that time, the lethal threat emanating from the Soviet Union was still providing the glue which bound the Allies together. Since then, however, circumstances have dramatically changed: a disastrous Trump presidency has hurt the credibility of the US as a guarantor of decent behaviour within the organization and has raised doubts about Washington’s commitment to action in the event of an attack against a NATO member. And notwithstanding NATO summit declarations and Moscow’s rogue international behaviour, it is a fact that the Russian threat is no longer perceived with similar intensity by all NATO members.

One NATO summit after another, the relevance of NATO’s added value on its southern flank is regularly questioned. Even though a paragraph of each official communiqué always religiously includes a nod to the issue by evoking NATO’s ‘360-degree approach to security’, the reality is that the slogan still lacks significant substance when one looks at NATO’s concrete added value in facing some important risks on its southern flank. Among the three core tasks of the 2010 Strategic Concept – collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security – crisis management is the weaker link, which in turn makes the common denominator of strategic interests more tenuous.

Read more: Rusi