An analysis written in the beginning of August just before the second crisis between Greece and Turkey is as relevant as ever. It was published in the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security by its Vice President Colonel (res.) Dr. Eran Lerman.

The Current Situation

The government-to-government meeting in Israel in which Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and some his key ministers joined their Israeli counterparts (June 16, 2020), was of strategic importance. Beyond questions of COVID-19 and tourism which dominated media coverage, the talks focused on responding to Turkish aggression in the eastern Mediterranean.

Ever since his ruling party was humiliated in municipal elections in the summer of 2019 (particularly in Istanbul), Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been busy promoting a nationalist-Islamist agenda. Among other targets, Erdogan aims at Israel, as indicated by many government statements which link the “Islamization” of the Aghia Sophia in Istanbul to the future “liberation” of al-Aqsa in Jerusalem.

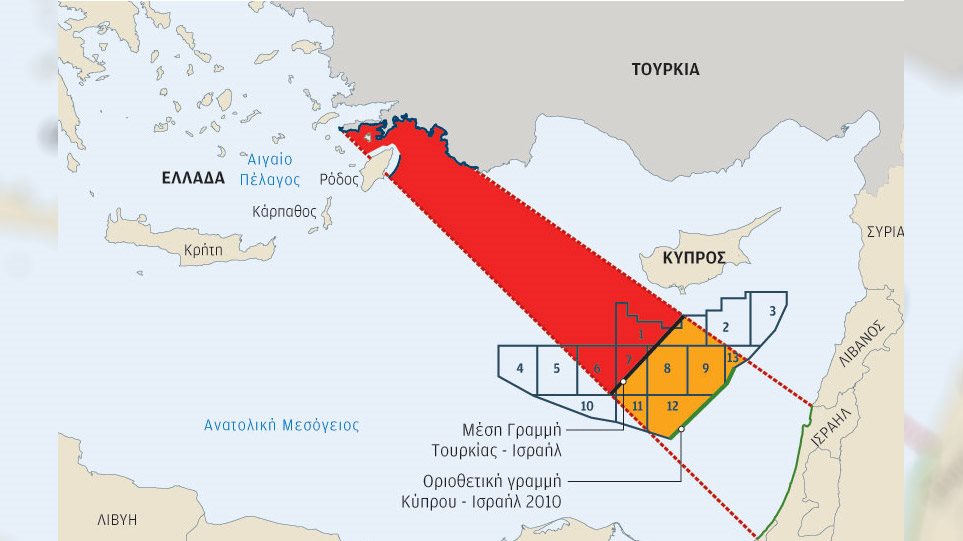

At the geo-strategic (and economic) level, the struggle is now focused upon the delineation of the Exclusive Economic Zone map in the eastern Mediterranean – an issue with significant consequences for Israel. This in turn is closely associated with the Turkish military intervention in Libya (and the possible Egyptian counter-intervention), as well as with Turkish prospecting for energy in Greek EEZ waters off Crete, and naval provocations near Rhodes.

For obvious reasons – above all, due to the dangers posed by Iran, and the resulting tensions in the north – Israel is reluctant to be an active partner in preparing possible war scenarios alongside Greece (or Egypt). It can and should, however, help by broadening the scope of intelligence cooperation; by working together on military acquisition projects, such as the joint development of naval assets; and in particular, by focusing attention on the “Archimedean point” in Washington. It will be the US position – Administration and Congress – which will to a large extent influence Erdogan’s level of strategic risk-taking and the scope of his “neo-Ottoman” ambitions.

The G-to-G Meeting in Context

On May 21, Israel and Greece marked the 30th anniversary of establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries. There was a celebratory joint statement of President Reuven Rivlin and his Greek counterpart Katerina Sakellaropoulou. (Their duties are largely symbolic in nature). Prime Ministers Binyamin Netanyahu and Kyriakos Mitsotakis shared a toast by Zoom.

Greek-Turkish crisis: Greek diplomatic counterattack on all fronts

Greeks and Armenians gathering at Evros borders in protest of Erdogan’s hostile policy

Their statements reflected the dramatic shift in relations between the two countries, compared with the early decades of Israel’s existence, when Greece gave clear priority to its interests in the Arab world, and even voted against the idea of a Jewish state at the UN General Assembly in 1947. This turn towards friendship has been cemented even during the rule of Alexis Tsipras and his distinctly left-wing party, Syriza (2015-2019); and now reaffirmed and strengthened with the center right Nea Demokratia (New Democracy) back in power.

In line with this transformation, and reflecting the growing intimacy in Israeli-Greek relations, the fourth government-to-government (G2G) meeting was held in Israel (on June 16, 2020), attended by Mitsotakis – who came with his wife and son – and six ministers of his government. They were Defense Minister Nikolaos Panagiotopoulos, Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias, Minster for the Environment and Energy Konstantinos (Kostis) Hatzidakis, Minister of Development and Investment Adonis Georgiadis, Minister of Tourism Haris Theocharis, and Minister of Digital Governance Kyriakos Pierrakakis.

As the joint statement indicates, the ministers discussed with their counterparts a broad range of cooperative projects now being established between the two countries (and in the Israeli-Greek-Cypriot triangle). These include projects in the fields of health policy; energy; environment; “smart cities;” agricultural development (with an emphasis of marine agriculture); investment, particularly in R&D; and cyber defense. This broad agenda is in line with the issues that have come up repeatedly in the tripartite summit meetings of Israeli, Greek and Cypriot leaders in recent years. (The Greek Minister of Health, Vassilis Kikilias, who is a staunch supporter of the alignment with Israel, did not attend the summit but he is scheduled to come on his own visit.)

Under the circumstances, media attention centered upon issues of tourism and civil aviation – given the eagerness of the Israeli public, in the Corona era, to be able to fly abroad. There was an announcement that Greece would enable the resumption of flights in early August 2020. Still, the actual text of the formal joint statement, which lists the full range of subjects under discussion, clearly indicates that at the strategic level, the G2G was mainly concerned with foreign policy and defense issues, and specifically, with aspects of the ever-growing challenge posed by the policies of Turkish president Erdogan.

Read more: jiss