TANTA, Egypt—Like the Jews before them, Christians are fleeing the Middle East, emptying what was once one of the world’s most-diverse regions of its ancient religions.

They’re being driven away not only by Islamic State, but by governments the U.S. counts as allies in the fight against extremism.

When suicide bomb attacks ripped through two separate Palm Sunday services in Egypt last month, parishioners responded with rage at Islamic State, which claimed the blasts, and at Egyptian state security.

Government forces assigned to the Mar Girgis church in Tanta, north of Cairo, neglected to fix a faulty metal detector at the entrance after church guards found a bomb on the grounds just a week before. The double bombing killed at least 45 people, and came despite promises from the Egyptian government to protect its Christian minority.

As congregants of the Tanta church swept the grounds of debris and scrubbed blood from the walls, a parishioner waved his national identity card: “This ID says whether we are Muslim or Christian. So how did that suicide bomber get into my church? If this identification isn’t for my protection, it’s used for my discrimination.”

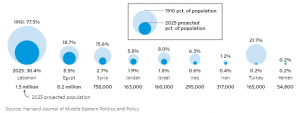

By 2025, Christians are expected to represent just over 3% of the Mideast’s population, down from 4.2% in 2010, according to Todd Johnson, director of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Hamilton, Mass. A century before, in 1910, the figure was 13.6%. The accelerating decline stems mostly from emigration, Mr. Johnson says, though higher Muslim birthrates also contribute.

The exodus leaves the Middle East overwhelmingly dominated by Islam, whose rival sects often clash, raising the prospect that radicalism in the region will deepen. Conflicts between Sunni and Shiite Muslims have erupted across the Middle East, squeezing out Christians in places such as Iraq and Syria and forcing them to carve out new lives abroad, in Europe, the U.S. and elsewhere.

“The disappearance of such minorities sets the stage for more radical groups to dominate in society,” said Mr. Johnson of the loss of Christians and Jews in the Middle East. “Religious minorities, at the very least, have a moderating effect.”

Ahmed Abu Zeid, Egypt’s foreign ministry spokesman, denied the government discriminates against Christians. “The presidency has been keen since day one to treat the Egyptian society as one nation, and one fabric,” he said, adding that the government is doing all it could to protect the minority and fight terror.

President Donald Trump expressed his confidence in President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi’s commitment to protecting his Egyptian population in a call between the leaders last month.

(Iraqis attend the Palm Sunday procession in the burned-out main church of the Christian city of Qaraqosh after Iraqi forces retook it from Islamic State militants)

Christian activists in Egypt say Washington’s ally in the war on terror has long discriminated against the minority, with recurring bouts of mob violence directed against Christians by their Muslim neighbors often leading to no arrests or charges in the courts. Christians have been barred from some government jobs, such as the state intelligence services, and laws make it virtually impossible to build or restore churches.

The exodus of Christians from the Mideast started about a century ago, with many heading to the U.S. for jobs as America opened its doors to migrants. Later waves stemmed from conflict, such as Lebanon’s civil war, and from fresh economic hardship, such as the U.S.-led sanctions in the 1990s that hobbled Iraq.

At the start of the 21st century, as wars waned, the oil business flourished in the Gulf region and a financial crisis hit the West, the Christian outflow ebbed.

Then in 2011, the outlook darkened dramatically. What started as hopeful revolutions across the Mideast largely degenerated into strife, civil war and the rise of extremist groups.

The outbreak of Syria’s multisided civil war in 2011 prompted about half of the country’s Christian population of 2.5 million to flee the country, according to Christian charities monitoring the flow. Many escaped to neighboring Lebanon, an anomaly in the region with Christians wielding political power and worshiping freely.

(Syrian Greek Catholics celebrate Palm Sunday at al-Zaitoun Church in downtown Damascus, Syria)

In Iraq, the instability that started in 2003, when a U.S. invasion toppled Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, deepened more than a decade later when Islamic State took over about one-quarter of the country. Iraqi church officials and the religion’s political representatives say only one-fifth of the country’s Christians remain of the approximately 1.5 million before 2003, according to estimates based on church attendance and voter rolls that identify religion.

Even though Iraqi forces have gained the upper hand over Islamic State, the country’s Christians show no sign of returning to homes they fled.

In northern Iraq, blue and white charter buses crisscross neighborhoods of recently liberated Mosul, returning Muslim families displaced by Islamic State. They drive through Christian areas without stopping. For the first time in nearly two millennia, Iraq’s second-largest city, once a melting pot of ancient religions, lacks a Christian population to speak of.

The Al-Aswad family, a clan of masons who built the city’s houses, churches and mosques and trace their lineage back to the 19th century, vow never to return. They’ve opted to live in the rat-infested refugee camps of Erbil in northern Iraq, where they await updates on their asylum application to Australia.

A Christian charity has given them a small apartment until June, at which point they will have to return to the refugee camps to live in a converted cargo shipping container.

“We call it the cemetery,” said Raghd Al-Aswad, describing how the cargo containers are covered with dark blue tarps to protect against the rain. “It looks like dead bodies stacked side by side with a giant hospital sheet on top of them.”

Mrs. Aswad fled Mosul with her husband, three children and in-laws in June 2014 when Islamic State took control of the city by routing Iraqi security forces, many of whom fled instead of fighting. The family was also run out of Mosul by al Qaeda in 2007, returning two years later.

Before the Aswads fled Mosul the last time, they left a bag of family photo albums with their Muslim neighbor, Ahmed Abou Hassan, for safekeeping. It was a risk for Mr. Hassan under Islamic State rules, one he says he gladly took.

Mr. Hassan couldn’t protect the Aswad home itself from the extremist group, which used it to house their fighters. The neighborhood was liberated in January. A recent visit by a reporter showed that the windows were broken, furniture destroyed. Weeds covered a cherished garden and tangerine tree.

Mr. Abou Hassan yearns to see his old friends again. “When the Christians come back to Mosul, hope will come back,” he said.

The Aswads say that won’t happen. “We don’t have any more trust,” said Raghida’s husband, Adwer. “This wasn’t the first time. The next time we might die.”

The Iraqi government says it is working to secure Mosul and other Christian areas so the minority can return.

“Terrorism has affected everyone and for sure the Christians as well,” said Sa’ad Al-Hadithi, a spokesman for the prime minister’s office. “The Iraqi government is working to alleviate all concerns by encouraging Christians to stay in Iraq since they are an indigenous group.”

Today, more Arab Christians live outside the Middle East than in the region. Some 20 million live abroad, compared with 15 million Arab Christians who remain in the Mideast, according to a report last year by a trio of Christian charities and the University of East London.

In 1971, Egyptian Coptic Christians had two churches in the U.S. Today there are 252 Coptic churches, according to Samuel Tadros, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom.

Mr. Tadros estimates that some one million Copts have fled Egypt since the 1950s, many to the U.S., Canada, U.K. and Australia.

(An Iraqi Syriac Christian priest gives the Eucharist during an Easter service at Saint John’s Church in Qaraqosh, Iraq, near Mosul)

Mr. Trump has indicated he would welcome more Christian refugees from the Middle East. His initial efforts to overhaul immigration policies have been blocked by the courts amid criticism his executive orders would discriminate on the basis of religion.

The Arab Christian diaspora in the U.S. has already emerged as powerful in politics and business. Dina Powell, Mr. Trump’s influential deputy national security adviser, is of Egyptian Coptic origin.

With the near-depletion of the Christian population in the Middle East and the recent flight of the Kurdish minority Yazidis from Islamic State, followed just a few decades after the flight of its Jews, many fear for the region’s future—not only because of the rise of radicalism but the loss of talent needed for sputtering economies.

Killed in the Palm Sunday attack at the church in Tanta was Mina Abdo, an engineer who left Egypt over a decade ago with his family, in part to allow his wife Yvonne to pursue her profession of gynecology.

Christian Egyptians have had a hard time getting work in her field since the 1970s when a fraudulent police report emerged accusing the sect of plotting to outnumber Muslims by performing abortions on unsuspecting Muslim women, or secretly slipping them birth control. The document has been likened to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fabrication used to discriminate against Europe’s Jews a century ago.

The family returned to Tanta after celebrating Holy Week for years in their adopted home of Kuwait City. In Egypt, they could sit under a steeple, which their church in Kuwait lacks because official churches are banned there. Mr. Abdo and his son, Kerollos, 11, took the front pews in Mar Girgis, which had a good view of the altar, where many of the family had been baptized and married.

When the suicide bomber detonated his vest that morning, the explosion mangled the same front pews, killing Mr. Abdo instantly. His body shielded his son, Kerollos, who survived but suffered shrapnel wounds to his face and right leg.

Two days after the attack, at a nearby hospital, Mrs. Abdo and her 14-year-old daughter, Miriam, tended to Kerollos. Mother and daughter wore the sweaters Mr. Abdo packed for their trip back home. Miriam wore her father’s crucifix, his wedding ring and hospital identity tag hanging off the thick gold chain—possessions the hospital put in a plastic zip-lock bag when Mr. Abdo was pronounced dead on arrival. His remains would stay in Egypt.

When asked whether she’d return, Mrs. Abdo hesitated. “I love Egypt. I love my memories here. But I’m scared now,” she said. “We will come back for visits, we must. My husband is buried here.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions