KIC 8462852 continues to puzzle and fascinate scientists. Its unusual flickering has provoked an outpour of explanation, ranging from comets to an alien megastructure. Although we are pretty confident that it’s not artificial in origin, all the natural explanations have yet to be confirmed.

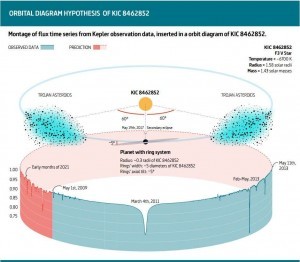

The latest suggestion, from a team of Spanish researchers, proposes a system where a ringed exoplanet orbits the star with two swarms of asteroids, one preceding it and one following it. The same arrangement is seen in the Solar System, where Trojan asteroids orbit around the Sun with Jupiter. A paper detailing the hypothesis has been submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, but it has not been peer-reviewed yet.

The researchers are invoking a phenomenon that’s established and understood, but to explain the changes in the star, they literally had to supersize it. The star was observed having several extreme and short dimming events that did not repeat. The team suggest a planet under 170 times the mass of Jupiter and the two Trojan swarms, which weigh about a Jupiter each. As a point of reference, the Solar System Trojans weigh less than 0.01 percent of our planet.

The team think that when we first looked at Tabby’s Star – named after Dr Tabetha Boyajian, the first author of the original study that described it – we caught the tail of the preceding swarm. Over the following four years, astronomers spotted an isolated and asymmetric 15 percent dip in 2011 (which this team claim was due to the ringed exoplanet) and then a series of small and big dips, which would be the following Trojan swarm.

“The first transit by itself was very interesting. The asymmetry and softness in the curve took us to consider something asymmetric. In fact, our first thought was a huge Star Wars Imperial Star Destroyer (because a triangular shape nicely fitted the asymmetry), but we very soon discarded it,” lead author Dr Fernando Ballesteros jokingly told IFLScience.

“More seriously, among the asymmetric and ‘triangular’ natural objects we could consider, we soon thought of a ringed body with a relatively high impact parameter and a small tilt in the rings. Once you think of such a big planetary object, the idea of it accompanying Trojans comes very quickly.”

Based on the observations provided by the Kepler telescope, the astronomers suggest that the planet has an orbital period of 12 years, which means this hypothesis can be tested in the early months of 2021. If they are correct, the preceding Trojan swarm should come into view then. But by using different techniques, it might possible to test this model already in 2020.

The researchers also have an explanation for the changes the Tabby Star has experienced recently, a dimming of about 3 percent.

“In our model, the recent dip is just the secondary eclipse, that is, the occultation of the planet by the star,” Ballesteros added. “In fact, one of our predictions was the intensity and timing of the secondary eclipse. We expected it for the first half of this year, dimming about 3-4 percent of the starlight.”

The dip from last week made the team decide to share their model, and they hope that this will spur more people into keeping a close eye on KIC 8462852, although they don’t expect any big change for a few years.

“Possibly the most interesting feature of our model is that it makes simple predictions,” Ballesteros stated. “We expect the recent dimming to be a single, small, isolated event – and then everything to be quiet until all hell breaks loose on Tabby´s Star again in the first half of 2021!”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions