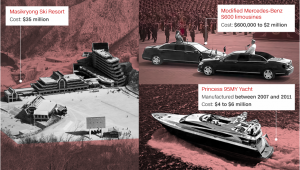

When the world’s most mysterious leader arrives for a parade, he steps out of a black Mercedes Benz and onto a red carpet.

But who sold North Korea’s Supreme Leader a brand new, top-of-the-line limousine?

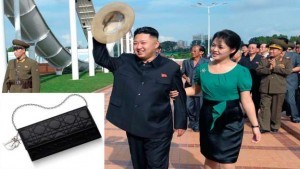

Despite international sanctions, Kim Jong Un continues to enjoy the good life, with recent purchases thought to include a gleaming white yacht, expensive liquors and even the equipment necessary to kit out a luxury ski resort.

Those expenses soon add up: The country purchased $645.8 million worth of luxury goods in 2012, according to a 2014 report from the UN.

To put that into context, in 2015, North Korean imports totaled $3.47 billion. But if you remove China — Pyongyang’s biggest trading partner — from the equation, the breakdown reveals North Korea spent more on luxury goods than it did on licit imports from the rest of the world combined, according to UN data processed by the MIT Media Lab’s Observatory of Economic Complexity.

So how can the leader a country that in March of last year warned its citizens to prepare for possible famine and severe economic hardship afford to live in such luxury?

Experts say these types of purchases are made using Kim’s personal piggy bank, filled by Pyongyang’s illicit dealings across the globe. North Korea has been accused of crimes such as hacking banks, selling weapons, dealing drugs, counterfeiting cash and even trafficking endangered species — operations that are believed to rake in hundreds of millions of dollars.

That money also helps pay for the country’s nuclear and missile programs, both of which Pyongyang believes it needs in order to deter any US-led attempt at regime change, experts say. North Korea’s nuclear aspirations have progressed forward rapidly despite sanctions, and Pyongyang has resisted any US attempts at negotiation that mandates de-nuclearization up front.

“North Korea has blatantly violated international law with their nuclear testing, illicit sales, and the ramping up of their nuclear program,” said Republican Representative Doug Lamborn, a member of the House Armed Services Committee and a leading advocate for missile defense in Washington.

It’s nearly impossible to track these illicit funds accurately, as they’re likely hidden away. But a 2008 Congressional Research Service report said Pyongyang could generate anywhere from $500 million to $1 billion in profits annually from its ill-gotten gains.

“North Korea will sell anything to anyone as long as they pay,” Anthony Ruggiero, a former deputy director of the US Treasury Department and an expert in the use of targeted financial measures, said at a panel sponsored by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies last week.

That money funds Pyongyang’s pursuit of a long-range nuclear weapon and the lavish lifestyle of the country’s elite, keeping them happy as sanctions cripple the economy, according to analysts CNN spoke to.

In the end, it’s an important way for Kim to cement his power and prevent challenges to his authority, experts say.

“That’s income that goes directly into the pockets or the bank accounts of the North Korean leadership. (Taking it away) can actually have a disproportionately large impact compared to trade flow,” said Sheena Greitens, a professor at the University of Missouri who has been studying North Korea’s illicit finance activities for the last 10 to 15 years.

In order to really pressure Kim until he’s desperate enough to get to the negotiating table on the US’ terms, US President Donald Trump may need to go after that money, analysts say.

(Click to enlarge)

But cutting off that revenue may prove difficult, like playing a game of international whack-a-mole.

“This is a regime that’s really good at finding new, creative illicit ways to earn hard currency and sometimes that’s coming up with new activities and sometimes it’s a matter of shifting geographic locations of those activities,” said Greitens. “If you wanted to try to pressure and contain North Korea’s ability to earn from these illicit activities, you’d have to also close off its ability to adapt.”

‘A pressure campaign’

Kim’s perceived flair for the dramatic — South Korean intelligence alleges he’s conducted anti-aircraft gun executions and complex assassination plots — is something he shares with his late father, Kim Jong Il.

The elder Kim was a noted cinephile and James Bond fan, and analysts say his fondness for spy thrillers appeared to influence his leadership — South Korea says he tried to assassinate enemies with a pen, kidnapped movie stars in order to boost the country’s own film industry and created of what’s known as “Office 39.”

The US Treasury Department says Office 39 is the bureau that “provides critical support to North Korean leadership in part through engaging in illicit economic activities and managing slush funds.”

The money basically hides in plain sight, according to Harvard-based North Korea specialist John Park.

“North Korean overseas networks have been extremely adaptive to the combined pressures of international sanctions, in large part due to their ability to nest and disguise their illicit business within the licit trade,” according to Park.

Though the Obama administration tried to target it with sanctions, Office 39 is still believed to be in operation.

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said the United States will try to further stymie North Korean operations by punishing third parties that help Pyongyang skirt sanctions.

“It’s a pressure campaign that has a knob on it,” Tillerson told State Department employees on May 3. “I’d say we’re at about dial setting five or six right now.”

Though Tillerson did not specify how those third-country sanctions would work, part of the strategy involves asking countries around the globe to scale back their diplomatic relationships with Pyongyang.

“What we are more appropriately asking them to do is to take a look at the diplomatic relations that they have with North Korea … North Korea, in many countries, has a diplomatic presence that clearly exceeds their diplomatic needs,” W. Patrick Murphy, the US State Department’s deputy assistant secretary in the bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, told reporters on a phone call.

Keeping them high and dry

North Korean diplomats around the world have been accused of using their diplomatic privileges to conducted crimes such as smuggling gold and running guns.

Embassy staff are useful to North Korea because they are mobile and can provide diplomatic cover for shady dealings, the United Nations says.

To cut off the illicit money, the US likely needs to deny North Korea the opportunity to use embassies as fronts for criminal operations, something the United Nations accused the country of doing in 2016.

“North Korea has been quite wily in recent years in trying to evade the UN Security Council resolutions … using diplomatic cover for some of its activities,” Murphy said.

That creativity may have been on display in recent years in Southeast Asia, where local and international authorities have accused diplomatic staff in connection with a potential assassination plot and an intricate arms smuggling operation.

To that end, one partner the United States says it’s pursuing to deal with North Korea is Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who’s serving as the chair of the Association of Southeast Nations (ASEAN).

Of the 10 states that belong to the regional organization, eight host North Korean embassies, according to the National Committee on North Korea. Another 39 countries around the world also host a North Korean embassy.

“If you think about strategy for attacking illicit sources of finance and pressuring illicit sources of finance, you’d actually want to go to some of the places that are flying under the radar,” Greitens said.

Whether US pressure works remains to be seen.

“The United States has been pressuring a number of Southeast Asian states for years now to crack down or reduce the extent of their relationship with North Korea,” said The Diplomat’s Prashanth Parameswaran.

“Southeast Asian states maintain these links with North Korea out of various considerations — diplomatic, cultural links, economic links. And they’ve proven that they want to keep this going on … these countries will make their own determinations with respect with what to do with North Korea.”

China factor

The US will need more than just buy in from Southeast Asia for the strategy to work, analysts say. They’ll need China too.

Beijing accounts for about 85% of Pyongyang’s imports, according to UN data. That’s a lifeline for the North Korean economy, one which prevents the US from really putting the squeeze on North Korea.

“You certainly want to cut off all areas of revenue but it’s really just sort of nibbling around the edges when you’re going to eventually have to come back to what you’re going to do about China,” Ruggiero, the former Treasury Department official, told CNN.

Convincing China to take comprehensive action that not only targets its own companies but could disrupt the power balance in the region will be no easy feat, according to David Cohen, former deputy director of the US Central Intelligence Agency.

China is most worried about destabilizing the Korean Peninsula and has proven they will act in their own best interest, Cohen said.

But Pyongyang’s reliance on Chinese entities also reveals an area of vulnerability, according to a recent study from C4ADS, a non-partisan Washington-based research group focused on exposing illicit trade networks.

“From 2013 to 2016, there were only 5,233 companies within China that either imported goods from, or exported goods to, North Korea. To put that number in perspective, as of 2016, 67,163 Chinese companies exported to South Korea,” the report said. “Targeting specific key nodes can have a disproportionate impact.”

President Trump has been courting Chinese President Xi Jinping for his help with North Korea. He hosted Xi at his luxurious South Florida Mar-a-Lago estate in April for a two-day summit, during which North Korea was discussed.

Trump’s language toward Beijing — on the campaign trail he said China was raping the United States — has softened since the meeting. Experts say Beijing’s seriousness about cracking down on its unruly neighbor may be the key to stopping Pyongyang’s illicit activities.

“It all comes down to China,” said Ruggiero. “In the end it’s going to require going after Chinese banks and Chinese companies that are complicit in North Korea’s sanction evasion.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions