Scientists recently found a new tool that allowed them to look inside an ancient Egyptian mummy: a high-energy particle accelerator.

The Hibbard mummy contains the body of a young Egyptian girl, estimated to be around 5 years old when she died at the end of the first century A.D. She lived in an agricultural community west of the Nile, and likely died of a disease like smallpox or malaria.

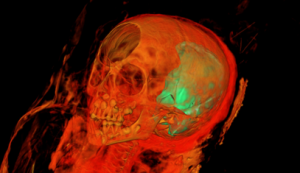

Northwestern University Researchers temporarily removed the mummy from its home in a collection at the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary at Northwestern University and brought it to the Argonne National Laboratory, located just outside Chicago. There, they used the Advanced Photon Source—the brightest X-ray source in the Western hemisphere—to look inside without risking any damage.

Archaeologists have used X-rays before. In 2016, Wired reported that X-rays were allowing researchers to read ancient texts that had been buried inside mummy-containing coffins. High-definition CT scans have been used to look at mummies, too. This, however, is the first time a high-energy particle accelerator, which is usually intended for physics-based research as opposed to medical or biological, has been used to look at mummified remains.

According to an Argonne National Laboratory press release, the mummy weighs about 50 pounds. It also contains more than just the girl’s remains.

The X-ray allowed researchers to examine the rich assortment of objects that had been buried inside along with the girl’s body. Shards, possibly from a bowl-like object made of tar (as opposed to glass) had been placed inside her skull after the brain was removed during the mummification process. Wires, the nature of which are unknown, were found in her teeth. And a small, mysterious object had been wrapped to her stomach.

“The resolution on the CT scan is such that we can only barely make out a shape. We think it’s some sort of stone, but we’re not sure,” Olivia Dill, a first year art history Ph.D. candidate who helped conduct the scan, told PBS NewsHour.

The mummy is noted for its “embedded portrait,” a realistic-looking face painted onto a wood panel rather than sculpted into a facade like mummies in popular culture. That portrait, along with the fact that the mummy was fully intact, was what first caught the attention of one of the seminary collection’s curators and resulted in the research team studying it with the particle accelerator.

“Our main motivation is to use the physical sciences to be able to unpack the technology of art,” Marc Walton, a materials scientist at Northwestern and one of the project’s leaders, told PBS. “We’re trying to get into the mind of the artist to understand why they’re making certain choices based upon the economics of the materials, their physical structure, and then use that information to be able to rewrite history”.

Source: yahoo.com

Ask me anything

Explore related questions