In a remarkable journey, an English pilot survived an ill-fated attempt to circumnavigate the globe in the late 1500s and wound up the first Western samurai of Japan.

William Adams was born in Gillingham, Kent, in 1564. His father died when the boy was 12, and young William was apprenticed to shipyard owner Master Nicholas Diggins. William spent the next 12 years learning shipbuilding, astronomy, and navigation skills that would provide him with a livelihood and ultimately his survival.

Adams went on to serve in the Royal Navy, one of those who fought against the Spanish Armada in 1588, and with the Barbary Merchants in the 1590s. While on one of his voyages to the Barbary coast, he heard rumors of a Dutch plan to send a large fleet to the Spice Islands of the East Indies. Five ships had been acquired and reluctant crews appointed. All the financiers needed was a skilled pilot to navigate the ships across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, according to “Samurai William: The Englishman Who opened Japan”, by Giles Milton. The risks were high, as were the potential rewards.

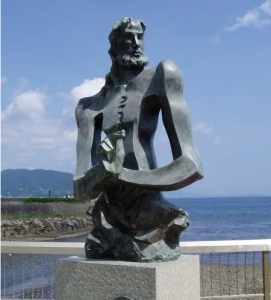

(Statue of Adams in Nagisacho, Japan)

Adams signed on. In June 1598, at age 34, he left behind his wife and two children and set sail as the pilot of a five-ship fleet bound for the Far East in what was triumphantly billed as the first Dutch circumnavigation of the world. His brother, Thomas, was on board as well.

The mission would turn into a disaster. None of the ships would complete the journey; few of the hundreds of sailors would survive; and instead of becoming rich, the financiers went bankrupt.

(From left to right: “Blijde Bootschap”, “Trouwe”, “‘T Gelooue”, “Liefde” and “Hoope”. 17th-century engraving)

The five ships left Rotterdam with the intention of reaching South America, but winds and bad weather drove them to Guinea, on the coast of West Africa, where they resupplied by aggressive means. From there, the ships set off for the Straits of Magellan, but only three successfully navigated the Atlantic-Pacific passage. Two of the ships, including the Liefde on which Adams sailed, met up on Floreana Island, off the coast of Ecuador. A violent encounter with islanders left many of the crew dead, among them William’s brother.

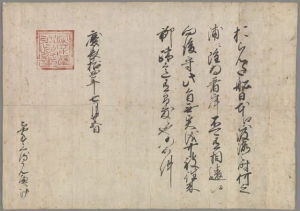

(The “trade pass” -Dutch: handelspas– issued in the name of Tokugawa Ieyasu. The text commands: “Dutch ships are allowed to travel to Japan, and they can disembark on any coast, without any reserve. From now on this regulation must be observed, and the Dutch left free to sail where they want throughout Japan. No offenses to them will be allowed, such as on previous occasions” – dated 24 August 1609)

The Liefde and the Hoop left Ecuador in November 1599 for the westward sail to Japan with only sketchy maps to guide them. They made at least one stop along the way, most likely on Hawaiian Islands, where eight of the crew jumped ship. Just two months later, a typhoon would sink the Hoop, killing all on board.

(A Japanese Red seal ship used for Asian trade – 1634, unknown artist)

By the time the Liefde anchored off the coast of Japan in April 1600, only 23 men still lived. Starving and sick with scurvy, they were unable even to stand. By the time they regained enough strength to make landfall, only nine of the crew had survived, among them Adams. The Liefde also carried valuable treasures: woolen cloth, jewelry, mirrors, tools, and weapons, including muskets, cannons, and cannon balls.

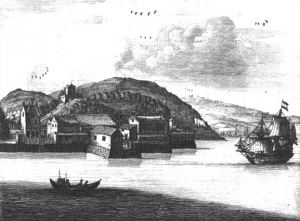

(The Dutch VOC trading factory in Hirado -depicted here- was said to have been much larger than the English one. 17th-century engraving)

Japanese locals and Portuguese Jesuit missionaries met the men on land. The priests decreed that the Protestant sailors should be executed. But luckily for the sailors, the local daimyo and future shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, first wanted to meet them.

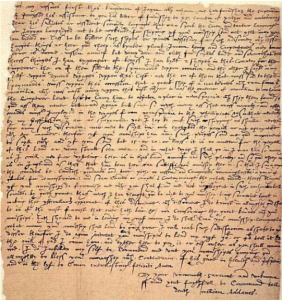

William Adams was summoned before Tokugawa several times, as Adams later recounted in letters home to his wife, which are collected in the book Letters Written by the English Residents in Japan, 1611-1623.

Adams was led into Osaka castle and after much bowing from servants, Adams found himself face to face with an “enormously plump man with long eyelashes and a wispy beard,” according to Samurai William.

(One of the two Japanese suits of armour presented by Tokugawa Hidetada and entrusted to John Saris to convey to King James I in 1613. The pictured suit of armour is displayed in the Tower of London)

The two men engaged in conversation, first through sign language and eventually with the help of a Portuguese translator. Tokugawa was fascinated by the world beyond Japan, and grilled Adams on war in his home country, European relations, and the routes that the sailor had traveled. Intrigued by the Englishman’s intellect and experience, the daimyo determined that Adams was more valuable alive for his knowledge than dead for his supposed Protestant heresies. In effect, Adams would undermine the Jesuits mission to convert the Japanese to Catholicism.

As Adams regained health, Tokugawa ordered him and his remaining compatriots to build Japan’s first Western-style sailing ship, which was used to survey the Japanese coast. Adams earned Tokugawa’s admiration and trust, and became a diplomatic and trade adviser, eventually a personal adviser to the shogun.

(Excerpt from a letter written by William Adams at Hirado in Japan to the East India Company in London, 1 December 1613. British Library)

That said, while Tokugawa allowed the other men to leave Japan, he wanted to keep Adams by his side. He presented the Englishman with two swords, symbolic of the rank and authority of hatamoto, or a samurai in service of Tokugawa, making Adams the first English samurai.

Tokugawa also bequeathed Adams with a new name: Miura Anjin, or the pilot of Miura. He was granted a large house in Edo (now Tokyo). And though he was still married to his English wife, Adams married the daughter of a court official, and he and his bride, Oyuki, had a son and a daughter.

(The monument to William Adams at the location of his former Tokyo townhouse, in Anjin-chō, today Nihonbashi Muromachi 1-10-8, Tokyo)

Adams made it his mission to establish trade between England, the Netherlands, and Japan. He never returned to his home country, and died in Japan in 1620, at the age of 55. In his will, he left half of his holdings to his wife in Japan, the other half to his wife and children in England.

Adams was largely forgotten until James Clavell discovered his story and adapted it into the 1975 best-selling novel Shogun, which in turn was adapted into a successful miniseries, a Broadway play, and several video games.

Today, memorial statues stand in Adams’ hometown of Gillingham and at the location of his former home in Tokyo. He is remembered every year on August 10th at the Miura Anjin Festival in Ito, which features re-enactments of the English samurai’s fateful relationship with shogun Tokugawa.

Source: thevintagenews

Ask me anything

Explore related questions