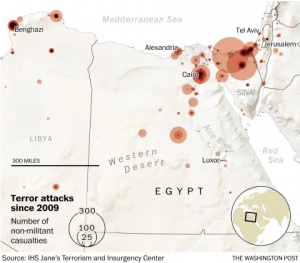

The desolate terrain of Egypt’s Western Desert is emerging as a new frontier in the global fight against terrorism.

Militant groups linked to the Islamic State and al-Qaeda are using the desert as both a haven and a crossing point for smuggling fighters, weapons and illicit goods from Libya, where lawlessness rules.

Along a highway stretching toward the Libyan border, the winds blow across a vast no man’s land of sand dunes, rocky scrubs and barren hills. There are no villages, no signs of life save for the cars and trucks that speed past. But this peaceful landscape, just an hour’s drive from Cairo, is the staging ground for an ambitious insurgency.

“It’s geographically a crucial place for the terrorists and extremists,” said Khaled Okasha, an Egyptian security expert and member of a government council to counter terrorism and extremism. “The presence of caves and hills makes it easier for them to attack and hide. And the capital is close. They can carry out attacks in a lot of nearby places.”

The ranks of the insurgents are being filled, in part, by fighters returning from Syria and Iraq, where the Islamic State’s caliphate has been dismantled, according to security officials and analysts.

Ominously, a new group linked to al-Qaeda has also emerged in the desert, announcing its presence with an attack in October that killed at least 16 security forces. This group, Ansar al-Islam, is now competing directly with the Islamic State, which had already been active in the Western Desert, introducing a rivalry that could fuel a further uptick in violence.

In recent months, the militants have been solidifying their presence along the Libyan border, moving freely across it with the help of sympathetic tribes. It is a reminder of the extent to which the instability that emerged in Libya after the Arab Spring revolts continues to spill across national borders.

While there have been sporadic attacks in the Western Desert since 2014, security officials and analysts say the Islamist extremist threat is escalating there, expanding beyond the northern Sinai Peninsula, where a virulent ISIS affiliate is combating Egyptian security forces. The militants have also struck in the heavily populated Nile Valley, which stretches from north to south.

The fighters in the desert potentially pose an even graver threat to the government of President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi than do fighters in Sinai, analysts said. Last month, the Egyptian military launched a campaign targeting militants in Sinai and the desert, underscoring the government’s growing concern about this front.

Egypt is using American equipment and military vehicles to surveil and patrol its 700 mile-long border with Libya. At the same time, the Sissi government is aligning with Russia in backing Libyan strongman Khalifa Hifter, who controls much of eastern Libya in the hopes that he will stabilize the border areas.

Yet, despite billions of dollars in military assistance from the United States and other western nations, Egypt’s security forces have struggled to control the flow of militants into the Western Desert.

“There are areas of the border that remain completely unsecured 100 percent,” said Mohannad Sabry, an Egyptian journalist and the author of a book on the Islamist insurgency in Sinai. “The attacks in the past few months tell a lot about how much the terrorists are able to mobilize across the border.”

The militant activity in the Western Desert has largely been overshadowed by the violence emanating from the northern Sinai. ISIS suicide bombers have blasted churches. Hundreds of minority Christians have been killed or injured in militant attacks.

Sufi Muslims, viewed as heretics by the Sunni extremists, have also been targeted. In November, militants who authorities said were affiliated with ISIS overran the Sufi al-Rawda mosque in the northern Sinai, killing more than 300 worshipers gathered for Friday prayers. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in Egypt’s history.

Meanwhile, attacks on security forces in urban areas by smaller Islamic extremist groups, with names like Hasm and Liwaa el-Thawra, that seek political change have risen in the past year, also catching the public’s attention. Hasm is the Arabic acronym for the Forearms of Egypt Movement.

The extent of the threat in the Western Desert became clearer in October. About 80 miles southwest of Cairo, not far off the highway, militants attacked a security convoy patrolling near an oasis, killing at least 16 soldiers and police. Military officials said more than 50 died, but the government disputed that figure, even attacking foreign media for reporting the higher number.

For security officials and analysts, the attack revealed that the situation in the Western Desert was more serious than the government had admitted. The attack was claimed by a little-known al-Qaeda-linked group, Ansar al-Islam, which declared a holy war against the Egyptian state, suggesting another lethal dimension to Egypt’s spreading Islamist militant landscape. Linked to Libyan extremists, the group has pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the network’s North and West Africa branch.

“The location of the ambush suggests that a new theatre of operations linked to Libya may be emerging,” wrote the International Crisis Group, a nonpartisan U.S. think tank, in a Jan. 31 report.

For the past four years, al-Qaeda and its affiliates have been quietly rebuilding in North Africa and elsewhere, preparing to fill any vacuum left by a weakened ISIS, terrorism experts say. In Libya and Egypt alone, there are now an estimated 6,000 fighters linked to al-Qaeda, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Al-Qaeda has systematically implemented an ambitious strategy designed to protect its remaining senior leadership and discreetly consolidate its influence wherever the movement has a significant presence,” Bruce Hoffman, a senior visiting fellow at the Council and former director of the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University, wrote in a brief last week.

Few Egyptians and westerners, though, have been aware of the deepening insurgency in the Western Desert. As in the northern Sinai, the Sissi government has banned journalists from traveling to many parts of the Western Desert, declaring them military zones. A crackdown on activists, researchers and nongovernmental organizations has further curbed the availability of independent information.

As in the northern Sinai, tensions have been percolating in the Western Desert since a military coup ousted the elected Islamist President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, two years after Egyptians rose up to topple President Hosni Mubarak. Morsi’s ouster and a subsequent crackdown on his Muslim Brotherhood party have helped fuel Egypt’s Islamic militancy.

In the winter of 2014, ISIS claimed responsibility for the killing of an American contractor working for Houston-based oil and gas exploration firm Apache Corp. in the Western Desert. That same year, militants killed 21 security force personnel at a checkpoint in Farafra, close to the Libyan border.

In 2015, a group of Mexican tourists were killed by Egyptian security forces who mistook them for militants, triggering a diplomatic crisis and criticism of the military’s efforts to govern the Western Desert. Last year, there was another attack on a checkpoint that killed eight police officers; four months later, ISIS militants slaughtered 29 Christians who were traveling in a bus to a monastery on the desert highway.

Security officials and regional analysts say the attack in October was designed as much for propaganda value as to inflict carnage or embarrass the Sissi government.

“We have started our jihad with the battle of the Lion’s Den in the Bahariya Oasis area on the borders of Cairo and were victorious against the enemy’s campaign,” Ansar al-Islam said in a statement following the attack.

Though relatively small, Ansar al-Islam is made up of highly trained former Egyptian army officers and soldiers who became radicalized, said analysts. The group is believed to have tried to assassinate Egypt’s interior minister in 2013; two years later, the group used a car bomb to kill the country’s chief prosecutor, according to security officials. They continue to recruit through networks in the army, analysts said.

“Compared to the insurgency in the Sinai, this is not a layman’s insurgency,” said Hause Waszkewitz, a Tunis-based regional analyst on Islamic groups. “They have military training and are comprised of former army members, which makes it very hard for counter attacks by the Egyptian army to bring these areas under their control.”

A former Egypt special forces officer, Hisham al-Ashmawy, is believed by security officials and analysts be the leader of Ansar al-Islam, as well as another militant group, al-Murabitun. He was once a leader in the Islamic militant group in the Sinai that became the ISIS affiliate, Wilayat Sinai. Ashmawy split off from Wilayat Sinai when they pledged allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and he formed his own group, Ansar al-Islam, that would later link with al-Qaeda. Ashmawy is believed to be operating out of the Libyan city of Derna, about 165 miles west of the Egyptian border.

Unlike ISIS in the Sinai, which is engaging Egypt’s military almost weekly, Ashmawy prefers fewer large-scale attacks.

“He is a ghost. He is a boogeyman,” said Zack Gold, an expert on Egypt’s militant groups at the Center for Naval Analyses. “Every major attack, he either has been behind it or has been blamed for it.”

The threat from the Western Desert is of particular concern, analysts say, because it could seep more deeply into the heavily populated Nile Valley, where militant cells can hide and receive help from sympathetic locals. “The threat of a spread into the Nile Valley is much more real and much more dangerous and much more likely from the Western Desert and from Libya than from Sinai,” Gold said.

Meanwhile, the growing rivalry between al-Qaeda and ISIS could trigger more attacks in the Western Desert as each group tries to outdo the other for more recruits, funding and safe havens, analysts warn.

Source: washingtonpost

Ask me anything

Explore related questions