In 1984, “Eleni” divided Greece yet again, reigniting civil passions. The book, a product of extensive research and based on hundreds of verified testimonies, tells the true story of Eleni Gatzogianni from Lia, Epirus. Eleni, a simple village woman, became a universal legend due to the immense success of the book written about her tragic fate by her son, Nikos Gatzogiannis.

Modigle Stearns, the US ambassador to Greece from 1981-1985, once told me: He hosted a dinner for Melina Mercouri and Jules Dassin. During the conversation, Melina furiously denied the events described in my book, calling them lies. Jules Dassin countered, “Melina, unfortunately, all of this happened. And that’s why you lost.”

In August 1948, at age 41, Eleni was tried, convicted, brutally tortured, and executed by the Democratic Army rebels. She was condemned for organizing the escape of her four daughters and nine-year-old Nikos, the youngest of her five children. She chose a horrific death over letting her children be abducted by communist rebels, a sacrifice that became a lifelong debt for Nikos Gatzogiannis. Fleeing war-torn Greece, he reached the USA, where, despite knowing no English initially, he was honored by President John Kennedy in 1963 as the best young journalist. Since then, Nikos Gatzogiannis, or Nick Gage, has become a distinguished investigative reporter and bestselling author.

Watch the trailer for the movie “Eleni” based on the book by Nikos Gatzogiannis: “Eleni (1985) Trailer.”

Gatzogiannis wrote about various significant topics, including the Watergate scandal, Mafia hideouts, and the tumultuous relationship between Aristotle Onassis and Maria Callas, always finding opportunities to highlight Greece. On the 40th anniversary of the Greek edition of “Eleni,” a work now considered a classic in civil war literature, “THEMA” met Nikos Gatzogiannis in Athens. They discussed his political views and experiences as a prominent Greek of the diaspora, devoted to his homeland.

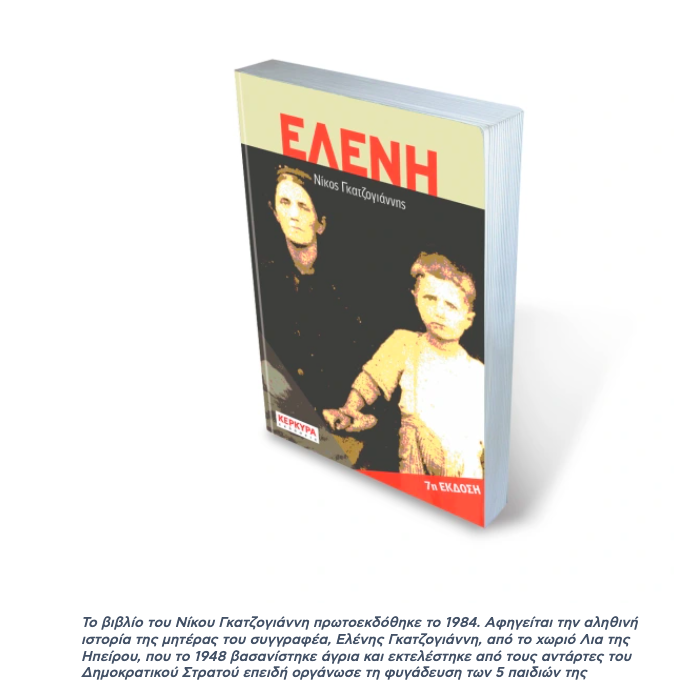

The book by Nikos Gatzogiannis, first published in 1984, narrates the true story of his mother, Eleni Gatzogiannis, from Lia, Epirus, who was brutally tortured and executed by the Democratic Army rebels in 1948 for orchestrating the escape of her five children.

Q: What has changed for “Eleni” in the 40 years since its publication?

A: For me, the most significant historical event of this period is the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 discredited the political philosophy and entire ideological edifice of so-called existing socialism, marking its end. At 84, I am extremely happy to witness the end of communism, not just in Europe, but even in China, where a one-party capitalist regime prevails. Today’s youth know little about communism and likely don’t wish to learn. In an era of explosive technological advancement, most young people aspire to become tech entrepreneurs, leveraging digital media and AI, rather than selling “Rizospasti” on street corners. From this perspective, communist obsessions seem laughable.

Q: Today, however, there is a rise of the Far Right internationally, not of the Left

A: Yes, unfortunately. Indeed, there is a trend towards the far right, marked by a surge in populism, which is always dangerous. Many citizens feel unrepresented by center-right parties that embrace contemporary ideological trends and are open to the left, alienating their base. Meanwhile, various figures seek to seduce this audience with misleading narratives, such as scientific denialism.

“Helen” captivated and divided Greek society like few other books in modern history. When the movie adaptation premiered in March 1986, it even sparked incidents outside cinemas, with the KNE blocking audiences from entering theaters and publicly criticizing you personally. Given that “Helen” is based on your mother’s true story, how do you explain these intense reactions?

In 1980, while I was a correspondent for the “New York Times” in Athens, I watched “The Man with the Carnation,” a Greek film about communist Nikos Belogiannis. Although I regretted that Belogiannis was sentenced to death for executing a secret plan without killing anyone, no one tried to prevent this movie from being shown. But when it came to “Helen,” the communists attempted to stop people from seeing it. This raises questions about their notion of freedom. Communists claimed to fight for freedom but only supported their own, censoring any opposing viewpoints. They spread lies and slander about my identity and beliefs, despite my extensive writings against the 1967 junta. I used every platform available to denounce the colonels’ regime because I believe any Greek-supporting dictatorship betrays our democratic heritage. I have always opposed any form of dictatorship, whether from the right or the left.

Q: In 1984, when “Helen” was published in Greek, wasn’t Greece vastly different from today?

A: At that time, PASOK was in power, and anti-American sentiment was prevalent, so few journalists attended the press conference for my book in Athens. Despite this, “Helen” sold 10,000 copies in its first week, eventually exceeding 200,000 copies. Its success prompted a fierce backlash from the Left after they saw its popularity. Ultimately, even leftists admitted the truthfulness of the book. No one dared to sue me because they knew a trial would reveal further damaging documents against the communists. The nightmare for the Left is that “Helen” documents the Civil War’s history, reflecting the broader implications of civil wars everywhere. As a result, “Helen” has become a reference work, recommended as a bibliography in universities worldwide.

The Left’s instinctive reaction to “Eleni” was almost uniformly hostile. How did you handle this?

I’ll respond indirectly. Modigle Stearns, the US ambassador to Greece from 1981-85, once hosted a dinner with Melina Mercouris and Jules Dassin. When the conversation turned to my book, Melina angrily claimed that “what Gatzogiannis writes never happened, it’s a lie.” Jules Dassin replied, “Melina, unfortunately, all this happened. And that’s why you lost.” Later, in 2004, when Corfu Publications republished my book, we held presentations in Athens and Ioannina with speakers like Karolos Papoulias and Theodoros Pagalos, both former communists. In Ioannina, protesters with banners shouted slogans like “Forget the hate.” I was warned they might disrupt the event, but nothing happened. This highlights the hypocrisy of the Left.

Q: You insist that everything in “Eleni” is true, but the reader finds it hard to believe that such horrors took place in Greece, specifically in your village of Lia, on the Greek-Albanian border, during the Civil War. For example, you describe your sister Glykeria, who stayed behind with your mother while you and your three other sisters escaped, witnessing a stream running red with the blood of corpses that had dammed it higher up the mountainside.

A: Certainly, the atrocities committed during the Greek Civil War were not limited to one side. The conflict saw severe actions from both the communists and the anti-communists. The period of dictatorship influenced the narratives, allowing different sides to propagate their versions of events at different times.

After the fall of the junta in 1974, left-wing narratives gained prominence, highlighting the injustices and persecutions faced by communists. However, this shift did not erase the violent acts committed by communist factions during the war. For instance, right-wing paramilitary groups, such as one led by a man named Galanis, targeted and executed suspected communists. Galanis admitted to killing those he captured, justifying his actions by saying that in war, you kill your enemies. His actions mirrored the brutal executions carried out by communist forces, such as the mass killing of 120 captured soldiers in the village of Tsamanta.

The Left argues that the Civil War was an inevitable response to the persecution faced by communists, especially after the Varkiza Agreement, which failed to stop the “White Terror” against them. This view posits that the communists were driven to rebellion by relentless oppression. However, there is also a counter-argument that the decision to initiate a civil war had long-term detrimental effects on Greece. The conflict stalled the country’s progress, causing a decade of stagnation and isolating Greece from the rest of Europe. This perspective holds that the communists should apologize for instigating a war that resulted in significant destruction and suffering.

Q: During an interview with Kostas Loulis, a leader of the Greek Communist Party (KKE), an American journalist bluntly stated that the years Loulis spent in prison were justified, given the violence perpetrated by the communists. This sentiment reflects the deep scars left by the Civil War on Greek society.

Q: In “Eleni” there is a strong opposition to dictatorship is evident in his consistent denunciation of the junta regime in Greece during his time as a correspondent for the “New York Times.” He viewed support for any dictatorship as a betrayal of Greece’s democratic heritage.

A: Regarding the persecution of communists, it’s important to acknowledge that they faced significant repression, starting with Venizelos’ “Idionymo” law in 1929. The legal persecution of the KKE and its members continued through various regimes, exacerbating the tensions that eventually erupted into the Civil War.

Q: Konstantinos Karamanlis, a pivotal figure in Greek politics, was marked by mutual respect, despite occasional disagreements. Karamanlis is known for his decisiveness and realism. For example, when you criticized the Foreign Minister’s performance, Karamanlis pragmatically responded that he had to work with the available resources.

A: The Greek Civil War was a complex conflict with atrocities committed by both sides. The narratives have shifted over time, influenced by political changes and the prevailing power structures. The author’s work seeks to present a balanced view, acknowledging the wrongs committed by all parties involved.

Q: But aren’t the communists also entitled to an apology, since they were already persecuted by Eleftherios Venizelos’ “Idionymo” in 1929?

A: In 1977, we did an interview with then Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis for the “New York Times.” The paradox is that he asked the first question, not me. “What do they say about me in America?” he asked. I immediately answered, without a second thought, “What they say about you in America is that you have made two big mistakes: the first is that you took Greece out of the military arm of NATO and now you are begging to rejoin. Your second big mistake is that you legalized the KKE.” Karamanlis started shouting, “They have no idea, they don’t know what the Americans are doing to them… They don’t know what the climate was like in Greece after the junta,” etc. Then I explained to him that the objection was not to the recognition of the KKE, but to its unconditional acceptance. Of course, in a democratic state, no political faction – as long as it is not a Nazi, criminal organization, etc. – should be outlawed. However, as I told Karamanlis, the Americans believed that a condition for the legalization of the KKE should have been that the communists apologize to all Greeks for the Civil War, the murders, and the destruction they caused in their homeland. Something similar happened in Spain.

Q: How was your relationship, in general, with Konstantinos Karamanlis?

A: Karamanlis did not seek my advice, but he respected the opinions I expressed. Every time I was in Greece, he invited me to dinner. He was a determined politician, extremely opinionated, self-centered, but also completely realistic as a leader. I once said to him, “President, I hear that Deputy Secretary of State X does not make a good impression on foreigners, he is probably not the ideal person for this position.” Karamanlis answered me with wisdom: “Niko, you always make an omelet with the eggs you have.”

Q: Are there any characteristic incidents from your meetings with him?

A: In 1985, when Andreas Papandreou did not nominate him as President of the Republic to extend his term for a second five-year term, Konstantinos Karamanlis fell into depression. Then Petros Molyviatis called me and said, “Niko, we have to do something for the President; he is very sad about what happened. Do you think Harvard University could give him an honorary degree? This would be good for the President because Harvard has never awarded a Greek politician.” I replied to Molyviatis that a degree from Harvard was something extremely difficult, because of the administrative structure of the university, with the board that decides, with very strict criteria, etc. But I agreed that I would do my best. So, indeed, I found the president of Harvard, made him a table with Greek food, and tried to convince him that Karamanlis was the greatest living Greek politician, that he deserved to be honored by the top university in the USA, etc. He agreed to recommend, if anything, the proposal to the Harvard board. And finally, it was approved. I couldn’t believe it either. I immediately, excitedly, called Molyviatis, who was equally delighted. However, after a few days, Molyviatis called me again. “Niko,” he said to me, sounding heavy, saddened, “the President says he won’t be coming to America for the award at Harvard.”

Q: Why?

A: Because the condition set by Karamanlis was to meet with the then-president of the United States, Ronald Reagan. I couldn’t believe my ears… But how could the US president meet Karamanlis? In what capacity? Karamanlis, typically, no longer held any office. He was a former prime minister, and former President of the Hellenic Republic, okay, but former. Nevertheless, I went to Washington and tried, through the White House chief of staff, whom I knew, to secure the appointment. As I waited, I was passed by Nancy Reagan, who approached me cordially as we knew each other well thanks to “Helen,” to whom Reagan had referred in a speech after his historic meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev. Nancy asked me what I was doing there. I told her, and she agreed to pass the request on to Ronnie. And, miraculously, Ronald Reagan agreed to host a dinner in honor of Constantinos Karamanlis at the White House the day after his Harvard award! Amazing! Another phone call to Molyviatis, again joy and excitement. Petros also jumped for joy, thanked me, and ran to tell the President. Except that he, again, had objections: “I’m not going to Harvard because I’m not expected to give a speech. Lord Carrington (former British Foreign Secretary) will speak in my stead.” And he canceled it. Thus, out of stubbornness and selfishness, Karamanlis was not awarded by Harvard, just like any other Greek politician.

Q: Is it true that you persuaded Karamanlis to become President of the Republic in 1990, mediating on behalf of the then Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis?

A: Yes, but the difference is that I went to Karamanlis on my own; Mitsotakis did not send me. Back in 1990, Konstantinos Karamanlis was saying he would not accept being declared President of the Republic if he did not receive at least 180 votes in Parliament. Mitsotakis had won the elections, and before I left for America, I went to say goodbye to him. By coincidence, I saw Georgios Rallis coming out of his office. With the boldness I had, I asked Mitsotakis what Rallis was doing there. He told me, “He wants to become President of the Republic.” Then I took Yiannis Paleokrassas and told him, “We need to go to Karamanlis.” And indeed, we went to his house in Politeia and I told him, “President, the nation needs you. You must become President of the Republic at this critical stage for the country. After the scandals and the ‘dirty ’89,’ the President of the Republic must restore Greece’s prestige. Only you can do that.” He insisted on the 180 votes. “Alright,” I told him then, “since you won’t budge from the condition you’ve set, the next President of the Republic will be Georgios Rallis.” And that was enough to convince him. Of course, he didn’t accept immediately; he said, “I’ll think about it, I’ll go to Corfu for Easter,” etc., but with an ego as big as his, Karamanlis could never tolerate Rallis becoming President of the Republic instead of him.

Q: Which Greek politicians from the Metapolitefsi period would you generally distinguish?

A: Konstantinos Karamanlis is a politician I admire because he led Greece back to democracy. However, I equally appreciate Konstantinos Mitsotakis, who did his utmost to strengthen democracy in Greece in the minimal time – just three years – that he was allowed to govern. From the prime ministers of the 21st century, I distinguish Antonis Samaras, who saved the Greek economy from complete collapse during a terrifying crisis, and finally, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who set Greece on a steady course after the disastrous period of Alexis Tsipras’ governance.

Q: Alexis Tsipras is lately trying to rebrand himself as a serious and reliable politician, to make a comeback, possibly as the leader of the Center-Left. Do you think he has a chance to succeed?

A: The problem with Tsipras is that he doesn’t understand the outside world, the developments taking place in Europe and the USA. Although I believe he is an intelligent man, he is charismatic and a very good orator. However, his problem is that he hasn’t studied abroad or traveled the world. On the other hand, the only thing I consider certain in politics is that anything can happen. For example, could anyone ever have imagined that Greece would have an openly gay party leader? Never. Yet it happened and is accepted.

Q: What do you think of the “Kasselakis phenomenon”?

A: I saw Stefanos Kasselakis at events of the Greek diaspora in the USA. I don’t believe he has experience in governance. He is not in a position to fulfill the duties of a leader of the opposition. He may enjoy this new game of politics, but when someone is involved in public affairs, they have to work hard, be prepared, and always be well-read.

Q: However, Mr. Kasselakis himself claims that he will be the next Prime Minister of Greece.

A: Ah, yes. And I will be playing center for the Boston Celtics from November, at the tender age of 84

Ask me anything

Explore related questions