Turkish government officials are careful in their public statements regarding the results of the U.S. presidential elections to avoid leaving room for misinterpretations from Washington and to prevent possible shadows on their relations with the new president, whoever that may be.

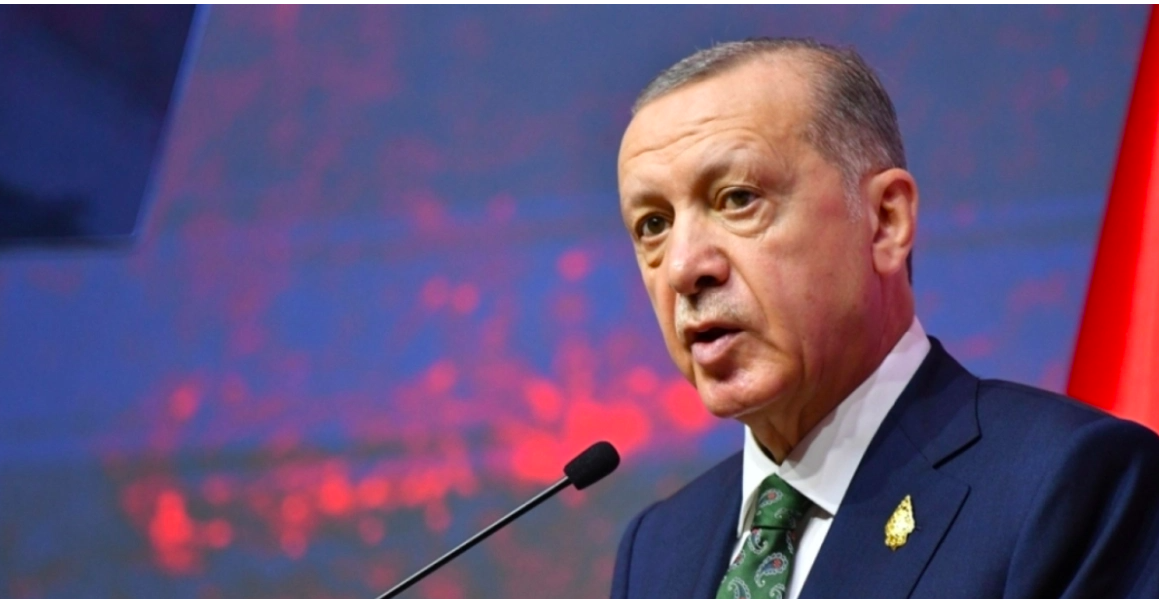

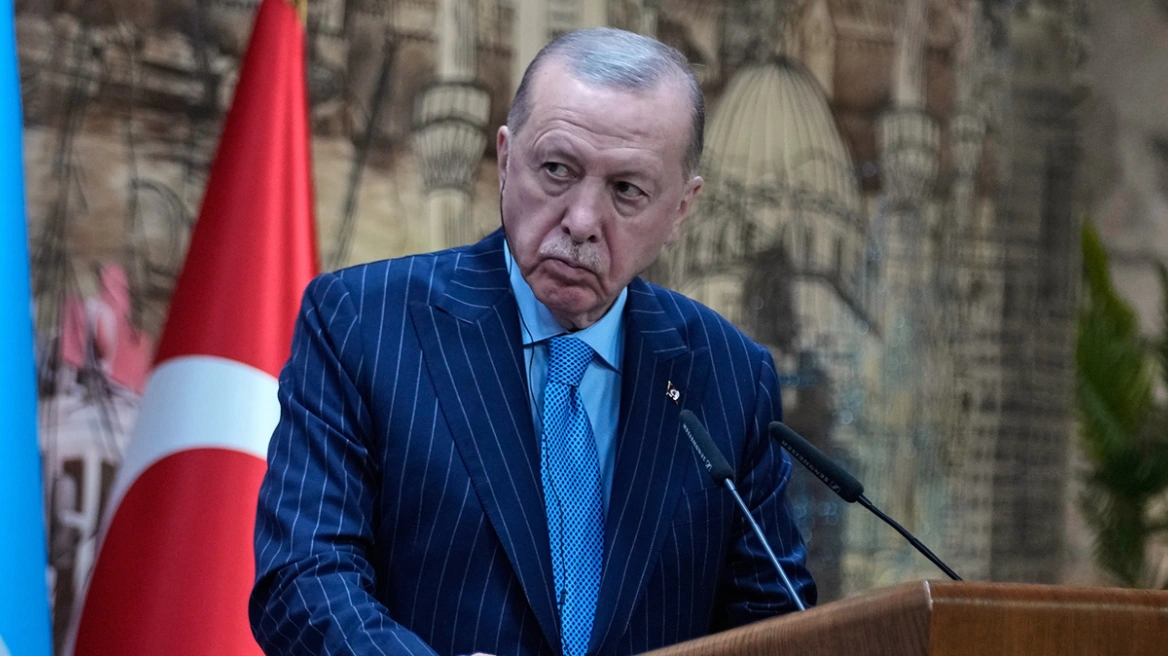

However, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself, when asked during his recent visit to New York for the UN General Assembly last September, stated: “I hope the next president will not make the incumbent look better. Because the issue of F-35s with the U.S. was not only experienced during Mr. Donald Trump’s period but continued afterward. All of them disappointed us. Both Republicans and Democrats.”

In Ankara, they see that Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris have different approaches to President Erdoğan. Sinan Ulgen, director of the Center for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (EDAM), reminds “Voice of America” that Erdoğan’s relationship with Donald Trump was strong during the latter’s presidency. The Turkish professor also predicts that “if Kamala Harris wins the elections, the relations between Harris and Erdoğan are likely to be much shallower,” similar to the relations between President Biden and Erdoğan.

A change in the upper echelons of American diplomacy, in the event of Trump’s victory, would likely allow the Turkish president to attempt to overturn the image of his country as an unreliable ally in Washington. This, of course, is to the extent feasible, as the differences in views between the two sides are not only a matter of personalities but primarily of conflicting political objectives—the U.S. is seen as an obstacle to the realization of Turkish ambitions in the region, at least in the current context.

There is, however, a prevailing belief among Turkish political analysts that the Turkish president would feel more comfortable with Donald Trump in the White House, despite the fact that the current relationship of “problematic alliance” between the U.S. and Türkiye is the culmination of a series of episodes that began during Trump’s presidency. In the November 2016 elections, the Turkish president supported Trump but later seemed to regret it.

However, it is not overlooked that Erdoğan met with the American president nine times during Donald Trump’s term, one of which was in Washington. Biden and Erdoğan, on the other hand, met only once and additionally had some brief informal meetings on the sidelines of international summits.

Kamala Harris has not provided much insight into her foreign policy. During her vice presidency, she participated in only two major international meetings. The first was as the head of the U.S. delegation at the Munich Security Conference in 2022. The second was the peace summit for Ukraine in Switzerland in June 2024. Many, however, point out the names accompanying her at these two meetings, who have significant experience in foreign policy: Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the Munich Conference and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in Switzerland.

Harris is more predictable compared to Trump

Harris is seen as more “predictable” than Donald Trump, which entails fewer risks, making her policy perhaps more reliable for Ankara.

On the other hand, Trump’s relations with Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had many extreme fluctuations in the past. In 2012, long before moving to the White House, Trump saw investment opportunities in Erdoğan’s Türkiye and decided to build the twin towers “Trump Towers” in one of the most expensive areas of Istanbul with the assistance of businesspeople close to the Turkish president at the time. But even later, when their relations became problematic, they maintained a channel of communication through their sons-in-law, Jared Kushner and Berat Albayrak.

The attempt at a military coup in 2016 did not leave U.S.-Turkish relations unaffected, as Erdoğan saw an American finger behind the bloody attempt to overthrow the Turkish government. The asylum provided by the U.S. to the preacher Fethullah Gülen, the mastermind behind the coup according to Ankara, reinforced this view. The death of Gülen on October 20 has now removed a significant burden from U.S.-Turkish relations, just before the change of guard in the U.S. presidency.

In the aftermath of the military movement, the case of American pastor Andrew Brunson, who faced a life sentence for his alleged involvement in the coup according to Turkish authorities, further weighed on bilateral relations. According to journalistic reports of the time, Trump refused to hand over Gülen in exchange for Brunson and ultimately succeeded in securing Brunson’s release by threatening to destroy the Turkish economy.

During Trump’s presidency, Türkiye was also expelled from the F-35 fighter program, in implementation of the “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act” (CAATSA), after Türkiye purchased the S-400 missile system, through which Moscow could gain access to the aircraft’s secrets and undermine its comparative advantages in battle. Türkiye will now have to negotiate with the next president of the U.S. whether there is a possibility of returning to the program and under what terms, or if and how it will achieve the return of the $1.45 billion it paid for its participation in the consortium.

Meanwhile, the case of the Turkish bank Halkbank has arisen, the management of which has been referred to American Justice on charges of violating U.S. sanctions against Iran.

The Kurdish Issue a Major Thorn

However, the Kurdish issue is emerging as a significant thorn in U.S.-Turkish relations. The civil war in Syria initially and the war in Gaza and Lebanon over the past year have redefined Washington’s approach to the problem, as it supports the Kurds in eastern Euphrates with its military presence in Syria. Türkiye views the prospect of creating a Kurdish entity—much less a state—in northern Syria, right next to its borders, as a threat to its territorial integrity. For Türkiye, the Kurds of Syria are synonymous with the PKK, which has engaged in armed attacks against it for 40 years.

Turkish journalist Fehim Tastekin describes how Ankara views its relations with Washington through the lens of the Kurdish issue, an approach that diplomats in Western capitals sometimes do not realize is the dominant perspective in the decision-making centers of the neighboring country and is largely driving Türkiye to redefine its relations with the United States. According to Tastekin: “The U.S. is using all its capabilities to change the balance of power in the Middle East with the help of Israel, its ‘executor’ in the region. We see that in this process, some take positions adopting the view that a new world will be created and the Kurds will take their place in it. Those making calculations centered around Rojava (i.e., the Kurdish-controlled northeastern Syria) position themselves as potential allies of the U.S., Israel, and Gulf countries. In this context, the collapse of the resistance axis extending from Gaza to Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Iran is seen as an opportunity. Of course, this impacts Ankara and assessments are made accordingly.”

In conclusion, for Ankara, there are currently three key open issues in U.S.-Turkish relations, and unless there are upheavals, these will be addressed by the next president of the United States after his inauguration in January:

a) U.S. support for the Syrian Kurds. In his previous term, Trump had promised to withdraw U.S. troops, a promise he ultimately did not keep. He even sent a historic letter requesting Erdoğan to reach an agreement with the military leader of the Kurdish-controlled Syrian Democratic Forces, breaking all diplomatic norms. The current U.S. government, on the other hand, has not given indications of an impending military withdrawal from Syria. In any case, a weakening of the U.S. military presence in the region is considered unlikely given the current conditions of war.

b) Türkiye’s purchase of F-16 aircraft. The implementation of the program has been set in motion, and both sides are negotiating at a technical level. No objections are expected in the event of a Harris electoral victory—after all, the agreement was finalized during Biden’s presidency. The Trump side has not shown its intentions.

c) The war in Gaza and Lebanon. Trump openly supported Israel, and Erdoğan’s corresponding support for Hamas may have implications. Harris, on the other hand, is likely to continue the current U.S. policy in the Middle East or distance herself from some choices of the Israeli government, potentially eliminating some friction points in U.S.-Turkish relations.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions