As is well known, Greece paid a heavy price during World War II. Hundreds of thousands of dead, destruction of critical infrastructure, and incalculable material damage. Almost everyone attributes the suffering of our country during those years exclusively to the Germans, the Italians, and the Bulgarians, who occupied Eastern Macedonia and much of Thrace. Of course, there were also the Cham Albanians, who murdered dozens of residents of Thesprotia and caused massive destruction in the region of Epirus.

However, very few people know that a major Greek city, the country’s largest port, Piraeus, was bombed by Americans (!) and Britons (!) on January 11, 1944. Why were these bombings carried out? No clear answers were ever given. Hundreds of innocent and unsuspecting Greek civilians were killed, families wiped out, and the city suffered enormous damages. The Germans seized the opportunity to accuse the Allies, a claim that was accepted by a significant portion of Greeks, to the point where the Germans even released funds for the “bombing victims” (a term that became widely used for the victims of the bombardment).

On the other hand, the Americans and Britons attempted to suppress the fact that their air raids caused the deaths of hundreds of Greeks, limiting their reports to damages inflicted on German facilities. Did the Americans or Britons ever issue even a single “apology” for the unwarranted bombing of Piraeus? Did they ever offer any financial compensation for the damage they caused to a nation that was not merely friendly, but one that, considering its size and population, perhaps contributed more to the Allied forces than any other? There is no evidence that they did. Let us delve into the tragic events of January 11, 1944.

The Bombing of Piraeus by Americans and Britons in 1944 and the Conspiracy of Silence

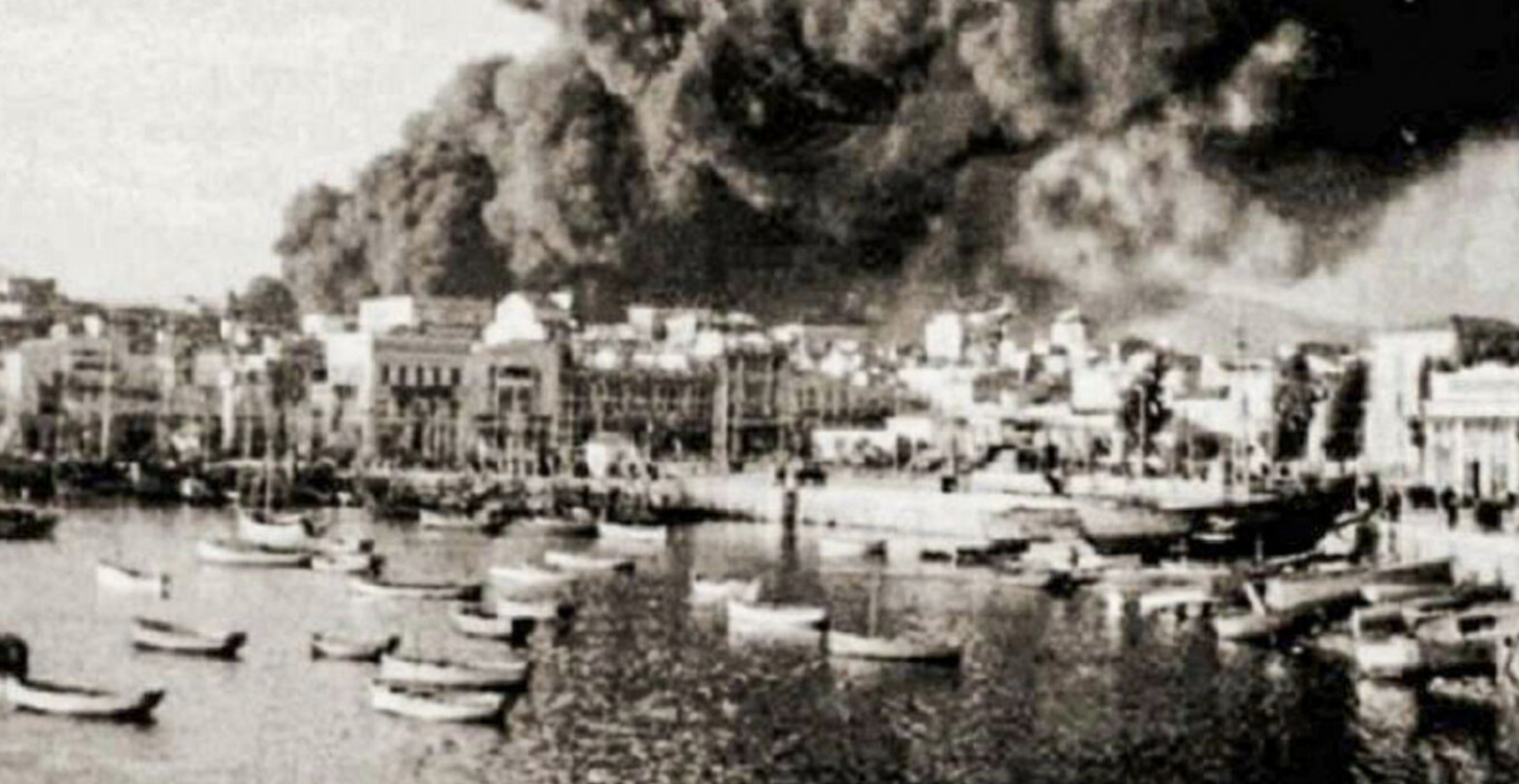

A view of Piraeus after the bombing

The Bombing of Piraeus During World War II

Like many other Greek cities, Piraeus was bombed numerous times, from the start of the Greco-Italian War almost until the end of the Occupation. During the Greco-Italian War, the attacks by the Italian Royal Air Force (Regia Aeronautica – RA) were not limited to operational zones and military targets but also struck densely populated areas of the country. Between October 28, 1940, and Christmas of that year, 21 Greek cities were bombed by the RA.

According to reports from the Deputy Ministry of Public Safety, between October 28, 1940, and March 28, 1941, just days before the German invasion (April 6, 1941), 589 civilians lost their lives due to RA air raids, more than 2,000 were injured, and over 20,000 were left homeless. In addition to Athens, Piraeus, and Thessaloniki, other cities such as Patras, Ioannina, Corfu, Volos, Preveza, Kastoria, Florina, Kilkis, Heraklion, and Larissa were bombed. Notably, Larissa was also struck by a strong earthquake (6.3 Richter) on March 6, 1941, killing 40 and injuring 100.

The Bombing of Piraeus by Americans and Britons in 1944 and the Conspiracy of Silence

Piraeus during the bombing

Piraeus was one of the cities most affected by bombings. Its dense urban layout and the lack of training in air defense tactics made heavy civilian losses inevitable. In January 1941, the RA bombed neighborhoods in Piraeus for the first time. Three members of the National Youth Organization (EON), who were assisting the wounded, were killed. On February 11, 1941, 20 people were killed and 11 injured in Tambouria. On April 6, 1941, the day the German invasion of Greece began, at 11:00 a.m., a German reconnaissance plane appeared over Piraeus harbor, causing alarm.

Workers, passersby, and residents near Akti Kallimassioti moved orderly toward a nearby shelter. However, panic ensued when a small cloud of smoke appeared at the tail of the plane (used to create shadows for ground target photography). People descending the steep stairs to the shelter began pushing those in front. Many “fell” and were crushed under others in the shelter. The outcome was tragic: 13 dead and more than 25 injured. That night, one (or three, according to other accounts) bomb(s) hit the British ship Clan Fraser, which had arrived in Piraeus two days earlier, loaded with ammunition and supplies.

The ship burned for five hours before exploding. The massive blast and subsequent shockwave caused significant damage to port facilities and dozens of homes within a radius of several kilometers. Two heavy bombings of Piraeus on April 24 and 26, 1941, targeting ships transporting troops from Greece to North Africa, resulted in numerous human casualties, the sinking of ships, and substantial material destruction.

The Bombing of Piraeus by Americans and Britons in 1944 and the Conspiracy of Silence

A police officer in front of ruins

The Allies took over from the Italians and Germans! The first known raid by the RAF occurred on the night of October 6-7, 1941. Five planes dropped 8 flare bombs and subsequently 105 bombs (!), 75 of which were incendiary. These hit a German supply depot, two Italian warships, the fertilizer factory, and a few houses. The planes flew at altitudes of 2–4 kilometers, facing German 88mm Flak cannons stationed in Prophet Elias, Chatzikyriakio, Drapetsona, Eugenia, and Aigaleo.

The German forces sustained no losses, but 20 civilians were killed and 20 others injured. A “weak” RAF raid on Piraeus and Tatoi on October 13 resulted in two civilian deaths and the destruction of four small houses in Drapetsona. Another British raid on May 1, 1942, struck the center of Piraeus (!), demolishing many homes on Kountouriotou, Ypsilantou, and Androutsou Streets. In June 1942, another 30 civilians in Piraeus were killed by the Allies.

However, the bombings that caused the deaths of hundreds of people and immeasurable material damage in Piraeus were carried out by Americans and Britons on January 11, 1944. The British RAF and the American USAAF are responsible for the events that will follow, events largely unknown to the public.

Here’s the English translation, maintaining the original structure, idioms, and tone:

Let’s look at some details about the planes of the USAAF (United States Army Air Forces) that bombed Piraeus and caused the most deaths and significant material destruction. On 09/25/1942, at Gowen Field near Boise, Idaho, USA, the 99th Bombardment Group of the USAAF was formed, under the command of Fay R. Upthegrone. It consisted of four squadrons (the 346th, 347th, 348th, and 416th) of bombers. The unit’s headquarters were almost immediately relocated to Washington. A total of 16 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, the so-called “Flying Fortresses,” were assigned to it. In October, the Group was transferred to Sioux City, Iowa, for the second phase of training. In mid-January 1943, the third phase of training began in Salina, Kansas, and by late February 1943, the B-17s flew to North Africa and were stationed in Marrakesh, Morocco.

The first mission of “The Diamondbacks,” as the 99th Bombardment Group was called because of its emblem, took place on March 31, 1943, with the aim of destroying the supply routes of the Deutsches Afrika Korps in Tunisia. Throughout 1943, the bombings continued, primarily targeting Italy. On July 14, 1943, the airmen of the 99th Bombardment Group bombed Rome for the first time, making superhuman efforts to avoid hitting the Vatican. On November 2, the 99th’s four squadrons, along with two more B-24 bomber groups of the 9th Air Force and two fighter squadrons, formed the new 15th Air Force, which, within 18 months, destroyed half of Europe’s oil production, many German fighters, and a significant portion of transportation infrastructure on the continent. Overall, the 15th Air Force dropped 303,842 tons of bombs on enemy targets in 12 countries, conducting 148,955 flights.

Initially, German positions in the Balkans were deemed of secondary importance, but from late November 1943, this strategy changed. On January 10, 1944, Sofia was bombed, resulting in many civilian casualties. The following day, January 11, 1944, it was Piraeus’s turn—referred to as Halon Basin on USAAF operational maps. Recent photographs had shown 10 German ships and another 20 requisitioned merchant ships in the largest port of Greece. At 9:30 a.m. on 01/11/1944, 84 B-17 bombers, along with another 20 from the 5th Bombardment Group, took off from airfields in the Taranto plain, heading for Greece. The B-17s were escorted by P-38 Lightning fighters of the 14th Fighter Group. The pilots faced a serious challenge: dense cloud cover at 5,500 meters. Visibility beyond the wings (!) of each plane was impossible. Twenty minutes before reaching the target, the bombers climbed to 6,600 meters (the planned bombing altitude). Then, a real tragedy unfolded.

The Bombing of Piraeus by Americans and British in 1944 and the Conspiracy of Silence

Small Children in the Ruins of Piraeus

Amidst the thick cloud cover, which reached 10/10, the last two Groups in the formation “collided into each other.” Three B-17s exploded. The B-17 of the Group’s commander made an abrupt turn, as did 2-3 other bombers. At least seven B-17s were lost in the clouds. A pilot from the 419th Squadron bailed out with his parachute. A B-17 collided with a P-38 due to the zero visibility. Considering that each B-17 had a 10-member crew, at least 80 men were missing before the bombing even began, while 1/10 of the B-17 bombers were rendered inoperable. The time was 12:35. Around 12:45, unsuspecting residents of Piraeus began hearing the drone of aircraft engines and soon saw them flying overhead. Eyewitness Nikos Saridakis recounts that they saw the snow-white planes and, in a frenzy of joy, greeted them with hands raised and waving handkerchiefs.

“It had been years since we’d seen our liberators, though not so close,” Saridakis concludes. Of course, very soon, everyone was proven wrong. At 12:55, the first six B-17s dropped their bombs on the target. At 1:11 p.m., the second Group launched the second wave of bombings. At 1:15 p.m., the entire formation was attacked by 15 Messerschmitt Bf 109s and 10-15 Fw 190s. Sporadic dogfights broke out between German fighters and the P-38s, lasting 15-20 minutes. Two bombers of the 99th Bombardment Group were hit by German aircraft, while six others sustained minor damage from the heavy anti-aircraft fire from the batteries of the SS Piraeus, Prophet Elias, and Kastella. The raid was not repelled, and the B-17s dropped at least 900 bombs on the urban fabric of Piraeus!

Only the first of these bombs likely fell into the sea. Due to their wide dispersion, they hit almost every neighborhood of the city: Amfiali, Evgenia, Drapetsona, Kaminia, Kokkinia, Agios Dionysios, Agia Sofia, Agios Nikolaos, Chatzikyriakeio, Kastella, Pasalimani, and Turkolimano. However, the center of the city paid the heaviest price, particularly the area from the ISAP station to Korai Square and the Municipal Theater. The first bomb likely struck the historic church of Saint Spyridon. When the alarm ended at 1:43 p.m. and the atmosphere somewhat cleared, the survivors witnessed horrific scenes: dismembered and mangled bodies, collapsed buildings, fallen columns, burned cars, and more. The Tinaneios Garden had been literally dug up, while the Municipal Theater was riddled with thousands of fragments. And as if all that wasn’t enough, a nighttime raid by a squadron of RAF aircraft dealt the city its final blow.

Bombing of the Piraeus Train Station

Although not comparable to the American attack, the second raid caused new casualties and delivered the final blow to many trapped individuals. The addition of new rubble over the HEAP shelter spelled doom for the young students of the Domestic Science School and the remaining 70 trapped individuals who were waiting to be rescued. Many deaths were attributed to “asphyxiation by burial.”

How many victims were there from the bombings of Piraeus? Considering that the bombings occurred 80 years ago, it’s easy to understand that rescues—and even the retrieval of bodies—were extremely difficult.

It’s telling that the victims of the January bombing were being buried up until June! According to eyewitness accounts, the German occupiers helped firefighters and civilians remove the rubble. They even began supplementing the few ambulances with military vehicles and personally used jackhammers to drill holes in the debris to allow oxygen to reach those trapped underneath. Newspapers of the time reported at least 1,000 dead, with some estimates reaching as high as 5,000. However, it seems the actual number of dead was closer to 650-700.

For the number of injured, the data is more reliable. Around 500 individuals were transported on January 11 and 12, 1944, to the “Tzaneio” and “General State of Nikaia” hospitals, while another 248 were taken to Athens hospitals, primarily “Laiko” and “Evangelismos.” German and Italian losses were minimal—10 German soldiers were killed, and six were injured, while four Italians died, and 43 were wounded. From a military perspective, the operation was considered a success by the Allies.

Approximately 80% of the German Navy accommodations (Marineunterkünfte) in Piraeus were destroyed. According to USAAF estimates, 26 ships in Piraeus harbor suffered major or minor damage. Large companies working on orders for the Germans—such as Drapetsona Fertilizers, Papoutsanis Soap Factory, and Retsinas Textile Factory—sustained severe damage. Two ammunition depots were destroyed, and a food storage warehouse collapsed completely. Greek firefighters attempting to extinguish fires in German warehouses had only three gas masks at their disposal.

Thousands of Piraeus residents fled the city using cars or other available means of transportation, heading for Athens or nearby suburbs. A characteristic example is Korydallos, whose population increased by 50% after the war.

Through a snowstorm, a convoy ascended Piraeus Street toward Athens. Those heading to the capital stayed with friends or were temporarily housed by State Welfare or charitable organizations. Hundreds of bomb victims settled in makeshift camps at the University Propylaea and Omonia Square. And as often happens in such cases, looting followed. At least ten individuals were arrested for theft.

One of the perpetrators, 26-year-old Aghisilaos Trombetas, a clerk at the Aeriofotos factory, was caught stealing items belonging to the German Army. He was tried by a military court, sentenced to death, and executed on January 15, 1944.

Hundreds of Greek prisoners in the Athens Military Prisons were more fortunate. The German Military Commander of the city decided to release those serving sentences of one to ten years—450 out of a total of 900 prisoners. Lastly, inmates from Haidari were transferred to Piraeus by the Germans to assist in any way they could.

The Aftermath of the Piraeus Bombings

As expected, the events in Piraeus provoked outrage and strong reactions in Greek public opinion. Resistance organizations labeled the bombings as a “senseless massacre,” and anti-British sentiment ran high within their ranks. The EAM of Piraeus even issued a statement condemning the Allies, calling the raid murderous. However, this announcement was soon withdrawn, and resistance organizations agreed that “the Allied raid conscientiously targeted military objectives,” as stated in the illegal newspaper Doxa of PEAN on January 15, 1944.

This was likely a gross misjudgment of the facts, considering the 700 dead, 800 injured, and the destruction of an entire city.

The collaborationist Rallis government and the heavily censored Athenian newspapers of the time characterized the bombings as a “crime” and labeled the Allies as “murderers of the people.” The government allocated 3 billion drachmas for Piraeus residents, a pitifully small sum given that a tram ticket cost 3,000 drachmas, and a newspaper cost 4,000 drachmas.

The few cars and taxis available charged a staggering 1,000,000 drachmas (!) for transport from Piraeus to Athens. Improvised chauffeurs demanded 300,000 drachmas for a seat on dilapidated buses. At that time, the monthly salary ranged from 1.2 to 1.5 million drachmas.

As we mentioned earlier, the Germans were quick to take advantage of the raid by the “Allied Grim Reaper,” as some newspapers called it. They even disbursed 300 million drachmas as an emergency relief fund to aid and support the victims. To emphasize their supposed sensitivity in contrast to Allied callousness, they republished the announcement from the Cairo Radio Station, which had been broadcast by the BBC at 6:30 PM on January 12, 1944, making no mention of civilian deaths:

“Piraeus suffered an attack yesterday during the day by American formations protected by fighter planes. Additionally, Piraeus suffered a nighttime attack by British combat formations.

Fires erupted, and explosions occurred. The attack was highly successful.” (Newspaper Kathimerini, January 14, 1944).

On January 15, the British Censorship Office or “Political Warfare Executive” issued written instructions to diplomats and correspondents clarifying: “Emphasize that Allied air operations are focused on military targets, including ports and airbases.” Nevertheless, the anti-German sentiment soon returned, as the Germans were accused of turning the city into a military base.

The Piraeus journalist Panagiotis Tzounakos, writing a year after the bombing, claimed that Rallis had been informed by the Allies about the impending air raid on Piraeus’ port and the city areas within a one-kilometer radius but said nothing to anyone. According to Tzounakos, the Germans committed a second crime. The Swedish freighters Viril and Halaren, which were docked in the port, received a radiotelegraphic warning at 11:00 AM on January 11, 1944, to leave the port within an hour due to an imminent air raid. The Swedes, whose country was neutral during WWII, hastily departed Piraeus around 11:20 AM. The Germans learned of the radio message and, starting at 11:30, began gathering their soldiers in the city’s safest shelters, leaving the people of Piraeus to their fate…

Ruins of Bombed Piraeus

Why Was Piraeus Bombed?

Evangelia Bafouni and Eleni Anagnostopoulou, in their article on the bombing of Piraeus published in Peiraika in January 2003, argued that the bombing of the city by the Allies was not accidental. A strong ELAS (Greek People’s Liberation Army) nucleus had developed in the city, and the 1st Company of ELAS Piraeus was considered exemplary. Following the city’s bombing, 2,500 Piraeus residents abandoned ELAS.

The Allies, according to the authors, did not act without a plan:

“…Everything indicates that the bombing of (Piraeus) was a premeditated action aimed at destroying not only one of the most important military bases in the Eastern Mediterranean but also the economic lifeblood of the country.

This would accelerate the Germans’ departure by depriving them of the resources they drew from exploiting its industrial infrastructure and workforce. This was done regardless of the human losses, which could be justified as an ‘unfortunate side effect.’ At the same time, it may have also been a show of force by the Allies—not only against Germany but also to send a broader message ahead of the ‘day after’ and the forthcoming redistribution of spheres of influence. A message, in other words, with many recipients.”

On September 25, 1944, the USAAF attempted to target the industrial zone of Evgenia-Keratsini-Drapetsona. The only outcome was the death of 50 people, 43 of whom perished collectively at the cemetery of Anastasis…

Sources:

“The Bombings of Piraeus by the Germans and the Allies,” Peiraika magazine, Volume 1, January 2003.

Jason Chandrinos, “The Great Bombing of Piraeus, January 11, 1944,” Military History magazine, issue 212, September 2014.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions