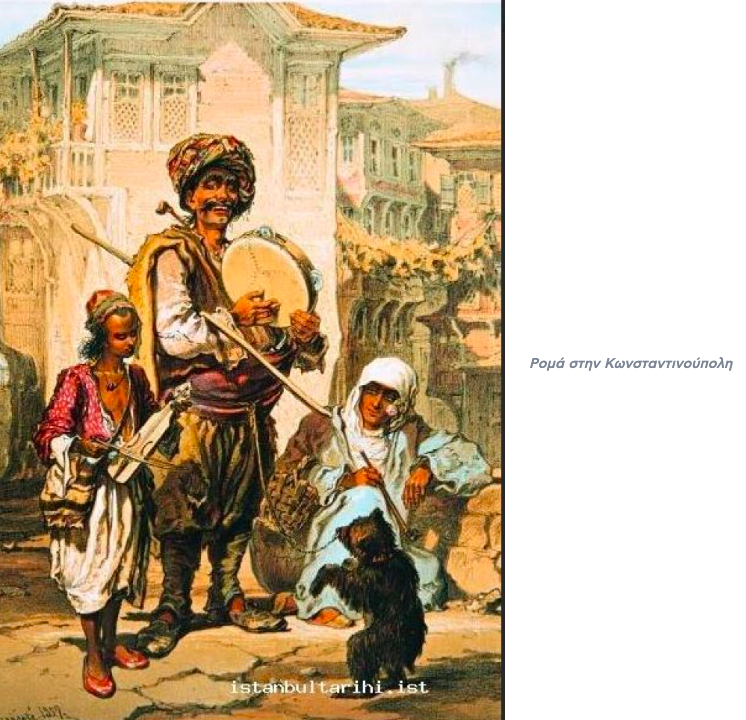

If someone refers to the “Roma” today, they are likely speaking of the ethnic group. However, in Byzantium, up until the 9th century AD, the term “Roma” had no connection to the community as known today, who were largely renowned in the Byzantine Empire. In that era, “Roma” referred to followers of a Christian heresy that first emerged in the Byzantine Empire during the 2nd century AD. This article explores why these people were called “Roma” and how the term later became associated with the Roma we recognize today.

Our primary source is the work of the distinguished professor of theology at the University of Athens, Ioannis A. Panagiotopoulos, titled “The Roma,” published in 2008 by Herodotus Publications. We extend our deep gratitude to the publisher, Mr. Dimitrios Stamoulis, for his support. Panagiotopoulos draws mainly from the writings of Ecumenical Patriarch Methodius I (843–847), particularly his work Methodius of Constantinople on Melchisedekians, Theodotians, and Roma.

The Theodotians and Melchisedekians: The “Predecessors” of the Roma

Christianity in its early centuries faced numerous heresies. It wasn’t just Arianism and Monophysitism—condemned by Ecumenical Councils—but also many other lesser-known heresies. Two of these, closely tied to this article, were the Theodotians and the Melchisedekians (or Melchisedekites). The Theodotians played a significant role in the development of Dynamic Monarchianism, with Paul of Samosata as their leading representative. Their spiritual father was Theodotus the Scythian, and their distinct community organization was attributed to Theodotus the Banker. The “Alogi” (meaning “irrational ones”) rejected the Gospel of John and diminished the divinity of the Word. The Alogi’s influence reached Theodotus the Scythian, who identified the Word with the Father. However, unlike the Alogi, Theodotus did not differentiate the Word from the Father and failed to define the divine nature of the Son. Theodotus was condemned by Pope Victor I (189–198), leading to his excommunication. His doctrine was carried on and expanded by Theodotus the Banker and Artemon (or Artamas), the teacher of Paul of Samosata. Theodotus the Scythian, originally from Byzantium, was expelled and went to Rome, where shoemakers were free citizens and often enjoyed economic power.

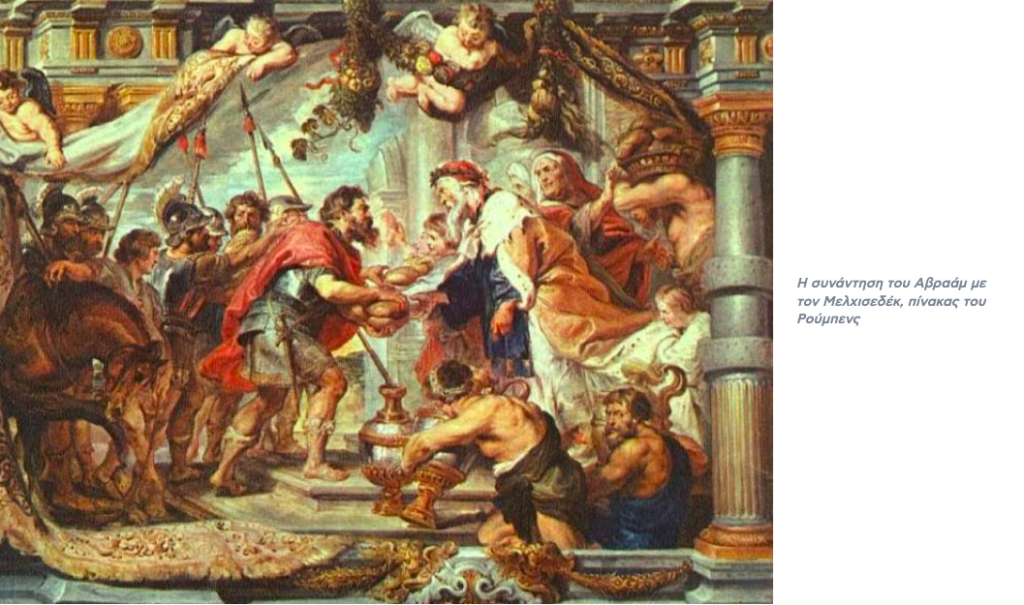

The Meeting of Abraham and Melchisedek, painting by Rubens

Theodotus was the first to claim that Christ was merely a “simple” human, a position that provoked Pope Victor I’s reaction. The Theodotians distorted biblical texts to align with their teachings, studying Euclid, Aristotle, Theophrastus, and especially the great doctor Galen, who was “possibly worshipped by some,” according to Eusebius. Hippolytus (died 235 AD) claimed that Theodotus the Banker “introduced” the doctrine of Melchisedek, arguing that his power surpassed even Christ’s. Professor Konstantinos Skoutéris emphasizes that “Theodotus the Banker recognized Christ as a power, just as the power of Melchisedek was greater than Christ’s. Christ was created in the image of Melchisedek.” Despite their influence, the Theodotian heresy seems to have disappeared by the 3rd century and remained confined to Rome. Notably, Saint Epiphanius (366–402) was unaware of this heresy, and Cyril of Alexandria (386–457) asserted that “no trace of them survived in his time.”

The Melchisedekians

While Cyril of Alexandria believed the Melchisedekians had disappeared by his time, Mark the Hermit, who lived around 430 AD, wrote works against them. Saint Epiphanius suggested that the Melchisedekites had split from the Theodotians. This heresy caused significant issues for the Christian Church, and many Church Fathers sought to refute the views of the Melchisedekians.

According to Timothy, a priest of the Great Church, in his work On Those Coming to the Holy Church (likely written in the last quarter of the 6th century), the Melchisedekians still existed in his time. They were “the ones now called Roma,” marking the first mention of the term “Roma.” Timothy indicated that their center was in Phrygia, and they were neither Jews nor Pagans. They observed the Sabbath, avoided circumcision, and refused to allow anyone to touch them. If someone offered them bread, water, or anything else, they would refuse to accept it directly, asking the person to leave the item on the ground, from where they would take it themselves. They followed the same procedure when offering food or drink to others. The term “Roma” came into use because they would not tolerate being touched.

Other Church Fathers, such as John of Damascus (650–750), were aware of the Melchisedekian heresy, but did not refer to them as Roma. Instead, Ecumenical Patriarch Germanos (715–730) exclusively used the term “Roma.” It seems that by the 8th century, the Melchisedekian heresy survived almost solely in Phrygia, but its followers were now called Gypsies.

Rituals and Beliefs

The practices of the Roma caused confusion even among notable Byzantine historians such as Aikaterini Christofilopoulou and Steven Bowman. The Roma often said, “Do not touch me, for I am pure,” a phrase based on the Gospel of John. It is almost unbelievable that if someone touched a Roma or gave them something, they would immediately undergo cleansing rituals and baths, as though they had become impure. According to Methodius, “this was an anti-Christian act” because Christianity, in its spread, marginalized such ritual cleansings, which were part of pagan worship of chthonic deities and ancient shamanistic practices. These cleansing rituals survived within the Roma community and contributed to their engagement with magic and divination.

The Roma were also influenced by the dynamic religious movement of early Jewish mysticism, known as Kabbalah, which emerged between the 6th and 7th centuries. This early form of Kabbalah is distinct from the modern Kabbalah, which only appeared in the 12th century. The roots of Kabbalah trace back to Merkaba mysticism, which emerged in 1st-century Palestine. Methodius also mentions auguries, omens, charms, and medicines. These forms of divination were divided into astrology-related practices and others. It is likely that the Roma primarily engaged in astrological predictions. Auguries were divinations based on human speech, while omens were derived from the flight of birds, a tradition that developed in Phrygia. Charms involved invoking the dead to achieve specific goals, and medicines referred to the use of potions with supposed healing properties.

Methodius not only describes the Roma’s beliefs but also their ceremonies. When someone sought their counsel, the Roma would accompany them to an outdoor location at night. There, they pretended to lead the Moon from the sky to the Earth, particularly to flowing waters such as rivers and springs. They claimed this action forced the Moon to answer their questions—questions from those who sought their help. In addition to astrology, they practiced magic, blending the two. Specifically, they invoked various demons (such as Soros, Sechan, and Archai) and selected stars to correspond with the person seeking help, using the star of the individual to counter the star of their opponent. This practice combined magical elements with Eastern astrology and Jewish demonology. The Ecumenical Council of Constantinople (691) strongly condemned divination and related rituals, officially disapproving of such practices.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions