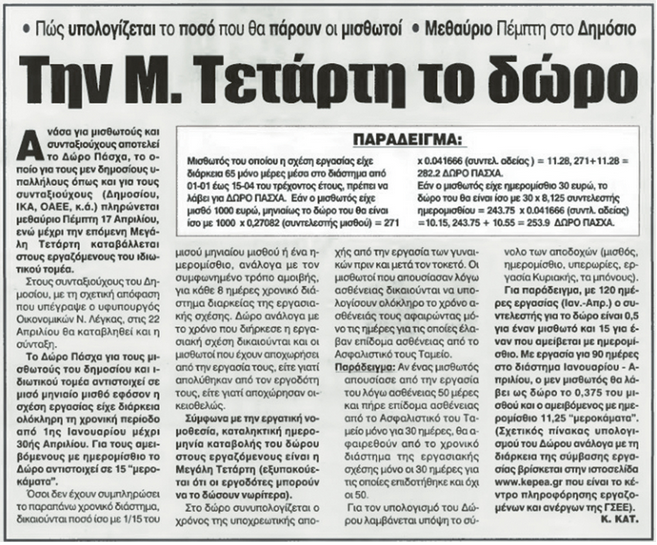

Once again, during the Easter period, the payment of the Bonus came to boost the purchasing power of millions of beneficiaries, easing the burden and bringing smiles to tens of thousands of families of private sector employees, in a financially difficult period due to the inflation that has been hurting the incomes of all for the past few years.

At the same time, however, it also provoked different feelings of nostalgia and bitterness for hundreds of thousands of active public servants and the approximately 2.5 million pensioners, who saw the Easter Bonus, which they used to receive at this time, as well as the Vacation Bonus, which combined to form the famous 14th salary, along with the Christmas Bonus, the 13th salary, being abolished by one of the many bailout laws in 2012. This was part of the heavy price imposed on our country by the creditors to save it from bankruptcy.

And today, the issue of reinstating all or at least part of these bonuses is back in the spotlight. Public servants and pensioners are protesting that they remain unfairly treated while the country has exited the bailout programs, and the government is trying to balance between what is socially desirable and what is fiscally feasible.

The First Demand in 1822

What very few people probably know is that the roots of the idea and the payment of the Easter Bonus are very deep. It goes back 203 years, to the years of the 1821 Revolution, when the new Greek state was literally in its infancy.

In fact, in a chronological reversal, the informal, even partially paid, 14th salary – the Easter Bonus – preceded the first payment and subsequent gradual extension to workers’ sectors and the eventual establishment of the 13th salary, the Christmas Bonus, by a century.

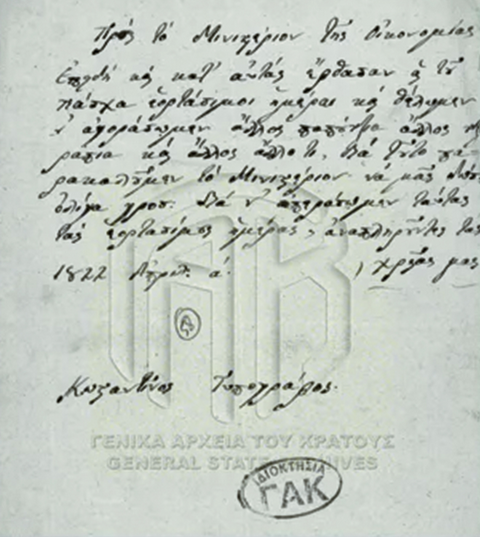

The paradox of the story is that the first to claim and eventually win the right to the Easter Bonus as an additional benefit from their employer were employees of the state printing office. The first reference to the payment of the Easter Bonus is found in a document from the workers of the Printing Office of the Administration to the Ministry of Finance on Holy Saturday of 1822, the second year of the revolutionary struggle.

At that time, the Provisional Administration of Greece had settled in Corinth. It was very alarmed, as on one hand, the tragic news of the destruction of Chios had just arrived a few days earlier, and on the other hand, reports had intensified that the Turks were intensively preparing a strong expeditionary force under Dramali, which would descend into the Peloponnese to crush the Revolution.

But the Provisional Administration was also intensely concerned with another headache. The request from the workers of the Printing Office of the Administration for financial assistance due to Easter. At that time, two printing presses were operating, one in Kalamata and one in Corinth. During the Revolution, others were also established in Messolonghi, Psara, and Athens. They produced nearly 50 books and pamphlets, 216 single-page prints, and seven Greek and foreign-language newspapers.

The machines they used had been sent as donations from the Greeks and Philhellenes of Europe. In 1822, the two editions of the Provisional Constitution of Greece from the First National Assembly of Epidaurus were printed in Kalamata. Laws, codes, and administrative orders were printed on 30 single-page sheets. The workers of the Printing Office of the Administration in Corinth had taken on the publication of the Government Gazette.

The head of the workers was the chief printer Konstantinos Tombras. He was, in an unofficial way, their union representative to the state. On behalf of his colleagues, he sent a request to the Provisional Administration asking for a few groschen because, due to Easter, they wanted to buy various things to celebrate the day. This letter has been preserved in the General State Archives (GAK) and it read:

“To the Ministry of Finance.

Because the celebratory days of Easter have arrived, and we wish to buy shoes, slippers, or other things, we kindly request that the Ministry give us a few groschen so we can spend these festive days, fulfilling our needs. April 1, 1822. Konstantinos Tombras.”

The Old “Charetlik”

The historian Thanos Vaghenas, in an article in the newspaper Allagi on February 18, 1952, argued that the Easter Bonus might have its roots even earlier, during the Ottoman occupation. He mentioned that it was an old tradition: “In our opinion, the provision of a gift for the holidays to the workers in the printing industry was a tradition even during the years of the Ottoman occupation. And this gift was called charetlik (from the Turkish word hayret = gift). The following is noted in the summary of that document: ‘Konstantinos Tombras, printer, to give him a charetlik. April 1, 1822. Corinth.'”

It seems that the request was satisfied, even if to a limited extent, as confirmed by another document in the General State Archives (GAK) addressed to the Ministry of Finance. It mentions that Konstantinos Tombras and three other printers would be given for a few days each: 300 drams of bread, half an oka of meat, 12 drams of oil, and half an oka of wine. One dram was equivalent to 3.203 grams, and one oka was 400 drams. However, printers were among the most demanding groups of workers of the time, as they were the first to go on strike in the newly established Greek state in March 1826.

The Establishment of the Payment

Nearly a century followed where the Easter Bonus, in a completely informal form and solely as a charitable provision from some employers, was given to certain groups of workers in money, in kind, or both.

Many owners of large businesses gave other bonuses with this (such as for marriage), while others offered benefits exclusively in kind to their workers, such as flour for workers at steam mills in anticipation of Easter, as reported by the newspaper Fos on April 7, 1916. Gradually, the payment of this specific benefit became more established in more and more categories of workers and sectors, though it was not institutionalized and always had many exceptions.

At the same time, there was no mention of such provisions for public servants or pensioners, as the state’s financial capabilities were scarce for many decades due to ongoing wars and other emergency difficulties. However, the truth is that in the last years of the 19th century and the early 20th century, the payment of the Easter and Christmas Bonuses became part of the demands presented and claimed by workers. Those leading the charge were the workers of public utility companies, such as electricity, railways, etc., which were then private.

Koundouriotis’ Decision

It appears that, over time, the payment of the two Bonuses became somewhat of a right for workers. As evidenced by a ministerial decision during the government of Georgios Kafantaris (Official Gazette 74/3.4.1924), signed by the regent Pavlos Koundouriotis for the personnel of the Athens, Piraeus, and Thessaloniki tramways, the decision reads, among other things: “For personnel with an official salary up to 500 drachmas, a bonus of 250 drachmas is given. For personnel with more than 500 drachmas, a bonus of 250 drachmas is given for the first 500 drachmas, and 20% for the remainder of the salary. The bonus is granted retroactively and will not be included in the 13th salary or in the bonuses given at Easter.”

For public servants, however, the government at the time, instead of providing salary increases, had earlier in the same month issued a law by the Minister of Finance, Emmanouil Tsouderos, granting an exceptional allowance to the lowest-paid employees.

Perhaps a precursor to the “emptying” of the floor of the Greek Parliament by Kostas Simitis by Andreas Papandreou, 63 years later, when once again the aspects of a restrictive income policy were being discussed, the prime minister… outbid the relentless demands of various parliamentarians to include employees in various legal entities and municipalities, regardless of their salaries, among the beneficiaries. For the first time, the issue of including pensioners in the bonus schemes was also raised.

At the end of the same year, the Federation of Electrical Technicians requested the payment of a full salary, including bonuses, for the holiday season, and the Minister of Communications responded that “the service is willing to arrange this, as it is an established custom.”

Backtracking by Pangalos

In 1925, exactly one century ago, during the government of the dictator Theodoros Pangalos, the payment of the Christmas Bonus, the 13th salary, became an official request of the public servants. On December 4, a committee of public servants presented the request to the Deputy Minister of Finance, Dimitrios Tantalidis, asking for the 13th salary to be given ahead of Christmas. At the same time, similar requests were submitted by the employees of the TTT (Post, Telephone, Telegraph), the precursor of the Hellenic Post.

The request was rejected, but the unrest among the workers grew, leading to new, intense strike movements.

The government backed down, instituted the 8-hour workday in various sectors, and eventually granted the 13th salary to electrical technicians, tramway workers, and railway workers. However, there was no unified legislative regulation for the Bonuses.

1945: Vacation Bonus

Immediately after liberation, the Emergency Law 28/1944 (there was no parliament) gave the Ministers of Finance and Labor the authority to set wages and daily salaries. Initially, the governments refused to meet the workers’ request for the return of the Easter Bonus due to rampant inflation. However, shortly afterward, at Christmas 1946, during the government of Themistoklis Sophoulis, the Bonus was paid as a special allowance and “in the form of the 13th salary.”

The vacation allowance with pay, which is the second part of the 14th salary, was established by Emergency Law 539/1945. This law also set the conditions for taking the first leave and how it would be calculated in subsequent years, either with the same or different employers. Since then, the provision of the 13th and 14th salaries has been generalized in both the public and private sectors. This system remained in place until 1980, when Law 1082/80 regulated the amount and the timing of the Holiday and Vacation Bonuses, which were all renamed as Benefits. Later, with Law 2084/92, also known as the Sioufas Law, these Benefits were no longer factored into pensions by the IKA (Social Insurance Institution). And then, the memoranda arrived…

Warning signals

The warning drums began to sound on August 6, 2009, when, amid the recession of the Greek economy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) advised the Karamanlis government to implement harsh cost-cutting measures, including the abolition of the Christmas and Easter Bonuses and the Vacation Benefit.

Instead of measures, early elections were held, and the new government of George Papandreou, after his famous “There is money” speech at the Thessaloniki International Fair and tax exemptions and delays in tax collections worth 1.2 billion euros, was forced, on March 3, 2010, to announce a new package of measures in the face of an imminent bankruptcy risk. This package included a 30% cut in the three Bonuses for public employees.

Two months later, the country officially entered a strict memorandum supervision via Kastelorizo. On May 2, as part of the first memorandum, the replacement of the 13th and 14th salaries of public servants with an annual bonus of 500 euros for all employees whose salaries were up to 3,000 euros was announced, with full abolition for those with higher salaries. For pensioners, the total bonus was set at 800 euros for pensions up to 2,500 euros.

These cuts were not enough. On November 7, 2012, with Law 4093/2012, under the Medium-Term Fiscal Strategy Framework 2013-2016 of the three-party government (New Democracy, PASOK, Democratic Left) led by Antonis Samaras, the full abolition of the three Bonuses for public servants and pensioners was implemented.

This was followed by SYRIZA’s commitment to the full restoration of the 13th and 14th salaries and pensions, which, however, was crushed by the complete refusal of the creditors. The “heroic negotiation” by the Tsipras government in the first half of 2015 led to the Waterloo of the third and most painful memorandum.

The pilot trial

Now, the controversial cuts of 2012 have been deemed constitutional due to the country’s fiscal situation, based on the decisions 1307/2019 and 1439/2019 of the plenary of the Council of State, under the presidency of Aikaterini Sakellaropoulou. However, last January, ADEDY (the Greek Civil Servants Confederation) intervened at the Athens Administrative Court in support of a lawsuit by a Ministry of Education employee who is requesting the permanent reintroduction of the Christmas, Easter Bonuses, and the Vacation Benefit, as well as the awarding of retroactive amounts from the past two years.

The request is also supported by the Union of Judges and Prosecutors, as well as by all opposition parties. The president of the Council of State, Michalis Pikrammenos, accepted the request for a pilot trial and set it for June 6, when the plenary session of the Council of State will rule on the case for all public employees. Will it uphold its previous verdict, or will the Council of State decide differently now?

No one disputes the improvement of the country’s finances, but the government argues that fulfilling the request is impossible due to the inevitable risk of fiscal derailment. The reintroduction of the 13th and 14th salaries and pensions in the public sector, according to the Minister of National Economy and Finance, Kyriakos Pierrakakis, would incur an overall cost of 7.8 billion euros annually. To cover such an expense, equivalent fiscal measures would be required, as Greece is obliged to maintain the net expenditure ratio at certain levels.

Equivalent measures of such magnitude can only come from the tax revenue side. Either by more than doubling the property tax (ENFIA), which would burden 7 million property owners, or by increasing the basic VAT rate by at least two percentage points, with the cost passed on to the prices of thousands of products and services.

Key Years

1822: The chief printer of the then National Printing House writes to the Ministry of Finance requesting a few grosia to allow workers to celebrate Easter.

1924: The regent Pavlos Kountouriotis signs a decision recognizing the entitlement to the 13th salary for tram workers.

1925: Theodoros Pangalos rejects the request from public employees for the Christmas bonus, as well as a similar request from employees of the TTT (Post Office, Telecommunications, Telegraph).

1946: Themistoklis Sofoulis pays the first post-war Christmas bonus, as an extraordinary allowance and “in the form of the 13th salary.”

1980: With Law 1082/80, the amount and timing of the payment for Holiday and Vacation Bonuses were regulated, and all were renamed as Allowances.

2010: Giorgos Papandreou, facing the risk of the country’s bankruptcy, cuts the 13th and 14th salaries (three bonuses) of public employees.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions