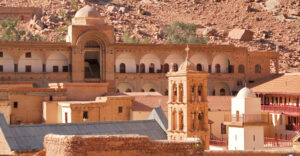

In the most impenetrable bastion of Orthodoxy, where time has stood still and faith has stood firm for 17 centuries, the Monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai is experiencing one of the most crucial turning points in its history. “THEMΑ”‘s delegates found themselves at the holy site, crossing the inhospitable desert and strict checkpoints to document an unseen reality: The monks who vigilantly guard the Hot Gates of Faith, the Bedouins who act as invisible guards, and a community that behind its austere walls reveals sacred images, relics, rare manuscripts and places that have touched history – a world of silent power that cannot be described, only experienced.

The route to St. Catherine’s Monastery is like no other. A simple choice in the itinerary – via Sharm el-Sheik instead of Cairo – saved us precious hours, as the former requires just three hours of driving, while the latter requires nearly eight. Even so, however, nothing on this route is easy or formal. The agency assigns you a driver, and it’s not just a driver, it’s your guardian in the desert. It knows when to stop and when to go on, how to speak at each police station, who to greet, where to show your papers. He knows that the journey to Sinai passes through roadblocks and armed police and soldiers.

The road is an almost eerie straight line through the desert. Hot air, silence, sand and mountains: the sun swallows everything, leaving no shadow. And suddenly a Bedouin with an empty plastic water bottle on the side of the road. The driver doesn’t brake. “We never stop at these things. It could be a trap,” he says, his eyes fixed ahead. The survival instinct is stronger here than the heat. When we approach the monastery now, the last check is the most thorough. We didn’t have to say who we were, they already knew everything: name, accommodation, route, contacts. And then you enter the monastery grounds. Being there is like returning to your childhood. To those years of innocence, when every Easter you looked forward to the classic religious films – the Ten Commandments, with Charlton Easton as Moses raising his hands on Mount Sinai and the sea parting in two. Watching the scene from a corner of the courtyard, you realize that nothing has changed. The same figures, the same looks. The Bedouins with their camels, their dark eyes and the desert dust on their clothes. The monkswith their silence carrying centuries. The landscape, austere and sacred. It’s like walking through the same movie that once captivated you in front of the screen. Only now you’re in it.

The guesthouse

It was, in the end, a wise choice to stay in the monastery guesthouse. Yes, St. Catherine’s has its own guesthouse for pilgrims, at a cost of about 90 euros a night, which includes breakfast and dinner. Don’t expect luxuries. Simplicity is the rule here. The room has two beds separated by an old-fashioned bedside table. A battered but precious air conditioner tries to keep the desert temperature at a tolerable level. In the bathroom, a bar of soap stands lonely, almost symbolic. There is, of course, the option of staying inside the monastery. This, however, requires special permission and a permit, a more time-consuming and limited process, especially for those who go for a retreat rather than just accommodation. The food in the hostel, while adequate, does not excite. Three small kebabs, a piece of bread and a simple salad make up our dinner – decent, but nothing memorable. The briam cooked by the monks inside the monastery is a revelation, we were told.

Walking through the gate of St Catherine’s Monastery is an experience that is hard to describe. Once inside, everything changes. It’s not just the coolness and the shade of the stone walls. It is the absolute silence that embraces you, a peace that makes you lower your voice almost by instinct. The space challenges you to stop, look around, and reflect on where you are. There is nothing fancy, just stone, simplicity and a sense that time has stopped. The first steps into the inner precincts of the monastery confront you with austerity in all its power. No unnecessary decoration, no sensationalism. Just bare walls, shade, a courtyard that seems motionless in time. There, the cave of Moses, in which, according to tradition, the prophet thawed out after leaving Egypt. And a few metres away is the burning bush, or, more accurately, the place where the bush still grows that is regarded by the monks as the natural descendant of the one who revealed himself to Moses with the flame that did not burn him.

The Church of the Saviour, dark and mystical, houses the core of the pilgrimage. There, under low light and the whispering of prayers, visitors stand before the icon of St Catherine. In front of it, carefully placed, is the bone of the saint’s hand. Some touch it, some look at it in tears, others simply stand silently. And somewhere there, among the dozens of pilgrims who arrive from the farthest corners of the planet, from Colorado in the United States, from Mexico, from countries one would hardly expect, the monks recognize a word in Greek. They look up in surprise. Their silence seems to recede for a moment, as if freed from an unwritten rule of abstinence. They return a smile, ask questions, almost with childlike curiosity. The Greek language brings with it more than words: it brings home.

3.5 million euros renovation of the library

Amid the climate of tension that had been caused by the Egyptian court’s decision to confiscate the monastery’s real estate, access to the library was far from straightforward. The monks appeared reticent, hesitant – not out of suspicion, but because they were experiencing multiple pressures from both Athens and Cairo. Behind every move they made, their consciences weighed heavy. The thought of closing, even for a day, the monastery as a protest against the decision had a political and symbolic cost. No one wanted to take initiatives that could be misinterpreted. And certainly, no one was willing to speak publicly about such a sensitive issue. Father Porphyry, who had formerly worked in newspapers, understood well the psyche of journalists. Perhaps that’s why he didn’t want to spoil our fun. He made sure to open the doors of the rare library for a while, letting us know, however, that time was limited and conditions were stifling.

Father Justinian, the monastery librarian, greeted us with understated courtesy and with that serene earnestness carried by people who have dedicated their lives to something greater than themselves. Without unnecessary words, he led us through the space that houses 11,500 books and more than 3,500 manuscripts – in dozens of languages, on parchment, on papyrus, on paper that seems ready to melt but will last for centuries. Among them, the Synoptic Codex, from the time of Constantine the Great, is in large print. A relic of incalculable value. And the Gospels, which bring to light a whole world of writing, faith and art, made by men who wrote in prayer. To see them up close is not just a visit to an archive; it’s like touching history itself.

The first discussions on the restoration of the library of St Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai began as early as 2000, when the Egyptian state, in cooperation with the monastery and the St Catherine’s Mount Sinai Foundation, expressed their desire to participate in the project through a tender with a domestic construction company. This involvement significantly delayed the start of work. The final initiative was taken by Archbishop Damian of Sinai and the Holy Synaxis of Sinai Monastery, who in 2014 gave the green light for the implementation of a difficult and complex project, which was completed four years later. The renovation was entirely financed by the Saint Catherine of Mount Sinai Foundation at a total cost of nearly 3.5 million euros. As explained to “THEMA” civil engineer and project manager George Sapiridis, a specialist in the restoration of Byzantine monuments, the role of Father Hesychios, architect and project designer Peter Koufopoulos and engineer Dimitris Dontos was crucial.

The difficulty in transporting materials through the harsh desert, combined with bureaucratic obstacles, turned the project into a real feat. Indicatively, half a million euros were spent on the construction of double-walled showcases alone, which ensure a constant temperature and ideal preservation conditions for rare manuscripts. At the same time, a state-of-the-art fire extinguishing system was installed: in the event of a fire, a special gas is released that “chokes out” the oxygen and automatically seals the room to protect the precious documents. The library was framed by handmade wooden furniture, crafted by the leading carpenters of Thessaloniki, giving the space an aesthetic that combines Byzantine simplicity with modern functionality. As Mr Sapiridis emphasizes, this is a model library, which meets the highest international standards of preservation and highlights the monastery not only as a religious centre, but also as a beacon of world cultural heritage.

Prayer to Allah

Just outside the main gate, in the monastery’s precinct, there is always someone watching: a plainclothes Egyptian policeman, unobtrusive, almost silent. He doesn’t carry a gun openly, he doesn’t wear a uniform, he doesn’t stand out from the visitors – and yet he’s there, always there. His presence does not cause discomfort; it is an element of the daily operation of the monastery, perhaps necessary in our days. One moment we see him stop. He opens a small prayer mat, spreads it on the ground and, facing the monastery, kneels down. There is no minaret, no mosque – and yet, he prays to Allah, against the backdrop of one of the oldest Christian monasteries in the world. It was an image full of power and symbolism. I asked him, politely, if he could repeat the gesture so I could take his picture. He smiled and declined politely. “I’m a police officer,” he said. “I’m not showing off. I only pray when I feel like it.” He explained to me that the monastery doesn’t cause him any restriction, it doesn’t bother him. On the contrary, he considers it a place of responsibility and mutual respect.

“At Sinai ,we have always lived together. Muslims and Christians. Muhammad himself had said never to touch this monastery,” he added. And he returned quietly to his seat, as if nothing had happened. A few meters away, a man stood alone, silent, with his arms crossed and his eyes watching everything around him. He didn’t look like a tourist, he didn’t have the attitude of a pilgrim. At first, we mistook him for an undercover policeman, and not without reason. At such a sensitive point, at a time of anxiety, it is normal to look around for people who don’t say who they are. We approached him as part of our effort to seek out persons who could talk to us for the story.

When we addressed him, he smiled and replied almost disarmingly, “Don’t worry, I’m not a policeman. I’m an archaeologist.” His attitude was calm, almost philosophical, and showed a man who knew the field and the situation well. When the conversation turned to the Egyptian court’s decision to confiscate the monastery’s property, he downplayed the tension that had been created. “The noise that has erupted is exaggerated,” he said. “If you read the ruling carefully, you will see that the role of the monks does not change. They will remain here, as always.”

He may be partly right, but the monks themselves do not yet have the signed decision in their hands. They remain cautious. And rightly so. For as long as the ownership is not explicitly clarified, no one can speak with certainty. And no one wants to be the monk who has put his trust in a system that could pull the rug out from under him tomorrow. Inside the walls of the monastery, the feeling is very different. The monks are not just alarmed, but furious. They may not speak publicly, but they convey their indignation. They have been informed that, as provided for in the decision, they will be required to pay rent for a small orchard within the monastery’s precincts, which they have cultivated for centuries. A piece of land considered an organic part of the monastery, of its self-sufficiency, of their life.

“Enough is enough…”, one of them said with an intensity not often found in monastic communities. And behind this phrase lies fatigue, suspicion and a sense of betrayal in the face of a state that, they fear, is beginning to quietly tear down what they have been building for 15 centuries.

The Bedouins

Right next to the walls of the monastery, as if a natural extension of it, are the houses of the Bedouins. Crude structures, low stone houses that fit perfectly into the architectural and rocky landscape of the Sinai desert. As if they had been shaped by time itself, with the same stone that the monastery was built with. Amidst camels, children and men in traditional kelebias, lives a tribe of people who have no identity, but have a role. They are the shadows that are always there, unseen guards, with a gaze that penetrates the visitor without touching him. The Bedouins live in total coexistence with the monastery. Together with their camels, they offer rides through the desert, along the paths that, they say, Moses walked on while keeping the Ten Commandments. The “full” package costs about $25, while for shorter rides, mostly for photos, the price drops to $5. There are more than a few who come just for the moment: a click with a desert background and a camel, an image that, for Bedouins, translates into survival. Everyone is trying to sell you something. From jewellery and key chains to Sinai ‘holy stones’, supposedly charged with energy. It’s their way to live, to survive, to stay there. Because beyond the trade and the camels, the Bedouins are also the vigilant guardians of St. Catherine’s Monastery. They know every passage, every corner of the mountain, every sound that doesn’t match the quiet of the desert.

Leaving the monastery, you leave behind more questions than you had when you arrived. Sinai doesn’t give you answers easily. It leaves you with images, silences and people who insist on living with faith not only in God, but also in their historic mission. Amid the turmoil caused by the court decision, with shouting, analysis and anxiety, another monk, without raising his voice, said something that has remained suspended as an epilogue: ‘St Catherine will have the last word on all this. And only she.” And we, as journalists, felt that we were not mere observers. We felt part of this mission: to protect, through the power of journalism, the historic Sinai Monastery. To stand beside those who silently, but with unwavering faith, keep the flame of a 17-century-old tradition unquenched.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions