Next weekend, at Miaoulis Square in Ermoupoli, Syros, the now-traditional international 3×3 basketball tournament will take place, organized by former top basketball player Giorgos Printezis and featuring dozens of current and former stars of the sport.

But beyond the highlights of the games, the eyes of the thousands of viewers who watch it inevitably turn — perhaps are even captivated — by the backdrop of the makeshift court set up for the tournament: Ermoupoli’s City Hall. A true jewel for the capital of the Cyclades, one of the largest and most imposing city halls in Greece. From its steps, which serve as an impromptu grandstand, spectators watch the matches.

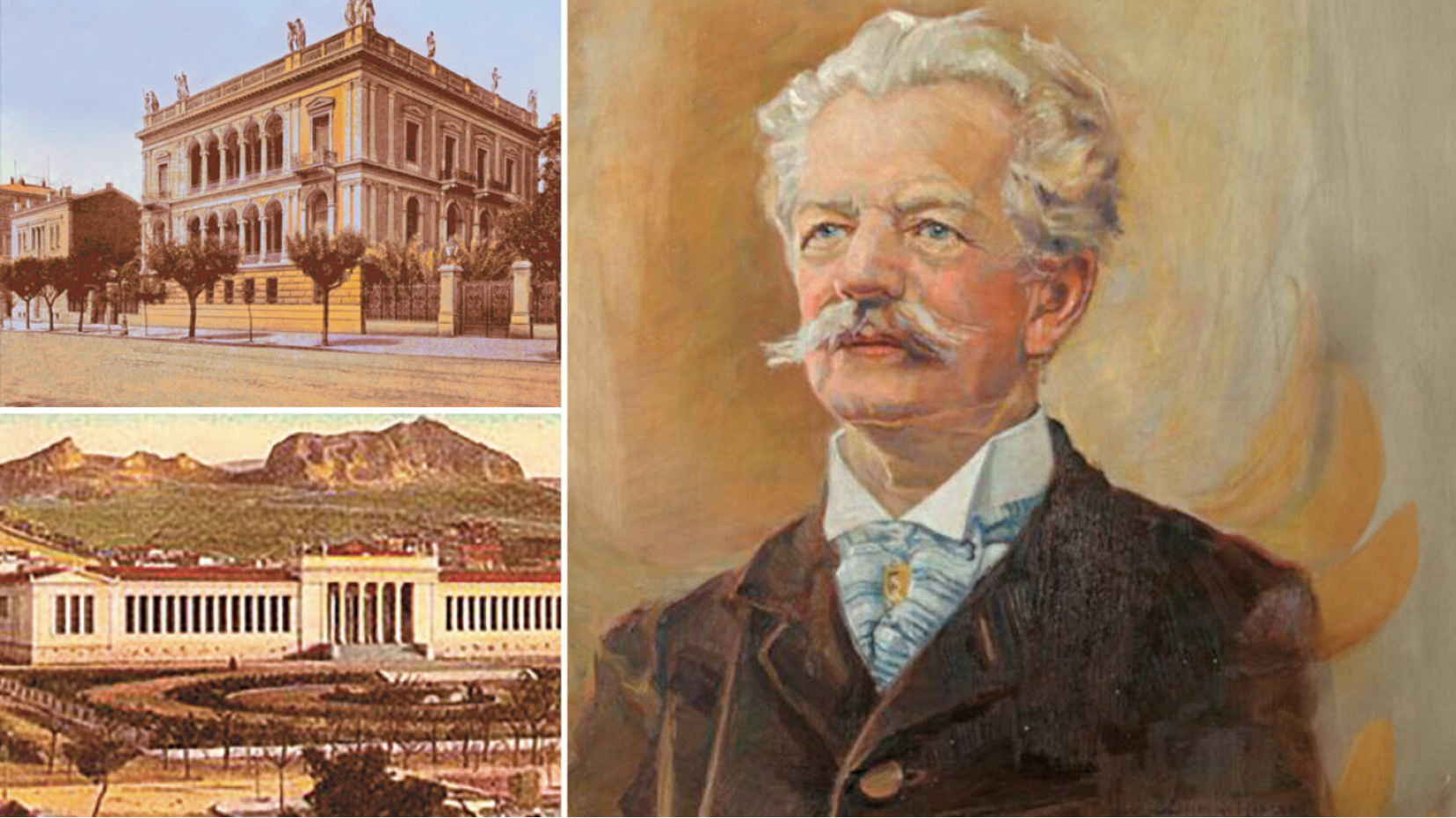

This building was constructed in 1876 under the supervision of Ernst Ziller, at the immense cost for the time of 1,300,000 drachmas. With a three-storey façade on the square side and two storeys at the rear, with impressive details, two wings with five vertical window axes on either side, projections, towers. Overall, it features a distinctive architecture inspired by three different styles: Tuscan, which characterizes the first floor with its imposing 15.5-meter-wide staircase; Ionic on the second floor; and Corinthian on the towers.

It is among the countless works bearing the signature of this leading German designer, architect, and builder. Scattered across Greece, they have left a vivid mark, shaped by his rich body of work that spans the last three decades of the 19th century and the early 20th. His creations have inspired admiration among later architects, as they are imbued with a creative spirit, a sense of artistic freedom, and a unique ability to blend ancient historical elements with modern trends.

Especially when walking through modern Athens, it is impossible not to be struck by the many public and private buildings whose presence so strongly shaped the urban identity and aesthetic of modern Greece — combining architectural tradition with innovative elements that gave the capital its new identity.

From today’s Presidential Mansion on Herodou Attikou Street and the Stathatos and Andreas Syngros mansions on Vasilissis Sofias Avenue, to the Iliou Melathron or Schliemann Mansion and the Academy of Athens on Panepistimiou Street, and on to the National Archaeological Museum on Patission Street, the National Theatre on Agiou Konstantinou Street, and many more iconic buildings in Athens and across the country: villas, theatres, city halls, even churches. All are admired by Greeks and foreign visitors alike. Few know their creator.

National Archaeological Museum: Changes to Ludwig Lange’s original design were made by Ernst Ziller

And yet, he went bankrupt

And yet this man, who came from Saxony to become the transformer of modern Athens — to whom many experts credit the feat of finding the Greek capital a “village” and turning it into a modern European city — ended up bankrupt. Swept along by the bankruptcy during Charilaos Trikoupis’ premiership, as well as by his own poor decisions, Ziller himself went bankrupt. He died penniless, having even lost his own home — another jewel of architectural inspiration and creation — to auction.

This in no way diminishes the fact that for modern Greek architecture, he was and remains an enormous and invaluable figure. In fact, 188 full years after his birth (22 June 1837), the full extent of his works remains unknown. There are many buildings — architectural gems in the provinces — of unknown architect that are attributed to him, though without certainty. Many buildings he undeniably designed and built have been demolished. In any case, his body of work has not been fully catalogued.

The first building

Ernst Moritz Theodor Ziller was born on 22 June 1837 in the district of Zerkowitz, today Radebeul-Oberlößnitz, Saxony. He was the eldest of ten siblings, son of builder Christian Ziller and Johanna Sophie Fichter. Architecture ran in the family’s DNA. He and three of his brothers — Moritz, Gustav, and Paul Friedrich — pursued careers in architecture and construction, with the latter even spending some years working in Greece.

Ziller studied architecture at the Royal Building Academy in Dresden. At the same time, he worked at the architectural firm of the famous Danish architect Theophil Hansen — his mentor and later close friend.

Ernst Ziller

His acquaintance with Hansen defined his career and ignited his relationship with Greece. This is because, in mid-February 1861, Ziller, just 24 years old, arrived in Athens as Hansen’s representative to supervise the construction of the Academy of Athens. He himself described it as the “will of Fate” that he should deal with the façades, plans, and sections of the Academy that his mentor was building on the commission of Simon Sinas in Athens.

The young capital of the Greek state was then nothing more than a “large village,” as he wrote in his Memoirs of Ernst Ziller. This work, by Dr. Marilena Z. Kassimati, art historian, includes his handwritten notes in German discovered in the artist archives of the National Gallery. A direct quote from his description of his arrival:

“We arrived in Piraeus. The trees along the road to Athens, which I had taken for old willows, were olive trees (the Olive Grove). The sight presented by the new section of Ermou Street was not at all cheerful; on the right and left, houses had been demolished to widen it. Going further up toward the café The Beautiful Greece, where turning left we ascended Aiolou Street, things improved somewhat, and so we finally reached the inn Vitalis, where we stayed. In short, Athens seemed to me like a large village.”

What he perhaps did not know then was that he would become the leading figure in the reconstruction of this “large village,” undertaking a vast amount of work involving profitable public and mainly private mansions.

From the Academy to Tatoi

Ziller integrated almost immediately into Athenian society. He began touring the then free parts of the country to get to know its archaeological treasures. He did not hesitate to visit even bandit-infested regions. In fact, while touring Rhamnous, he encountered the notorious bandit chief Kitsos Nyfitsas and his gang. Fortunately, they took him for a poor schoolteacher and left him unharmed. After King Otto’s ousting, work on the Academy stopped, and Ziller left Greece.

He returned to Vienna, where he continued working at Hansen’s office while studying Architecture and Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. He also took part in study trips to various Italian cities (Verona, Rome, Florence, Venice, Pompeii, etc.), where he conducted on-site architectural studies.

In 1868, Ziller returned to Greece, and in 1872 he was appointed professor at the School of Arts, the precursor of the National Technical University of Athens. Commissions for plans and designs came one after another. Ziller had now established himself.

He enjoyed the favor of King George I, who assigned him the design of the summer palace at Tatoi, the Petalioi Islands, and later the heir’s palace. These projects acted as a magnet for many wealthy grandees, who commissioned him to design and build their mansions and country villas.

Fortunately, his clients’ names are recorded in his surviving studies. During 1872–1885, clients came to him, not the other way around. Among them were the Psycha, Syngros, Pesmazoglou, Kalligas, Syrioti-Empeirikos, Stathatos, Melas, Dekozis-Vouros, and Gouvis families, along with dozens of other wealthy figures of the time.

Ziller married pianist and composer Sophia Doudou, daughter of a businessman from Kozani. They met in early 1876 in Vienna and married in June of that year. They had five children: Valeria, Natalia, painter Iosifina (Fifi), Otto, and Walter.

In 1883, he was dismissed from the Polytechnic for refusing to cover up financial mismanagement delaying the Zappeion’s construction. The next year, Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis appointed him director of Public Works to rehabilitate him, but he had to leave the position when it was abolished in 1893 after the Greek state’s bankruptcy.

His philosophy

Ziller gave architectural identity and aesthetics to the capital of the new Greek state, linking it to its distant ancient past. He was a key figure in shaping and developing mature Greek classicism, replacing Roman stylistic elements with Greek classical ones, essentially creating his own school and a unique architectural movement still studied and admired today. In private residences, he moved towards eclecticism and romanticism, while in public buildings he maintained the Greek spirit of classicism. In ecclesiastical architecture, he sought to preserve Byzantine tradition.

He excelled in theater architecture (Municipal Theater of Athens, Apollon Theater in Patras, Foskolos in Zakynthos, Royal [National] Theater in Athens), church design, museum architecture, and external building decoration with wrought-iron railings, and richly painted interiors.

He was the first architect to use iron supports in construction, introduced artificial ventilation and central heating, and established cast-iron railings with designs inspired by mythology. A characteristic example is the swastika, found during Schliemann’s excavations in Troy, which he used in the railings of Schliemann’s house on Panepistimiou Street.

He conducted excavations at the Theater of Dionysus and the Panathenaic Stadium (1864–1869), at Troy, and at Rhamnous near Marathon. He was among the first to record the polychromy of statues and architectural elements of the Theseion, Erechtheion, Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, etc. In 1865, with his study On the Original Existence of the Curvatures of the Parthenon, he was the first to provide documented support for the correct view of the Parthenon’s intentional curvature.

Bankruptcy and destitution

With the 1893 bankruptcy came the sudden collapse of his architectural and contracting office. As in modern crises, when the state defaults, it brings down banks and many businesses. Thus, the fragile Greek construction sector was the first to “pay the price” of bankruptcy.

The partial marble restoration of the Panathenaic Stadium in 1895, in preparation for the 1896 Olympics, based on plans by Ziller and Anastasios Metaxas, gave him a brief financial reprieve. But his financial woes worsened year by year. He was overwhelmed by debts and lost almost all his property, even forced to sell personal belongings to survive. Even his home, the splendid Ziller Mansion, was sold at auction in 1912 to banker Dionysios Loverdos.

He died at the Poorhouse on 10 November 1923 and was buried at the First Cemetery of Athens. Adding to the tragedy, from World War II until 1990 many of his masterpieces were demolished or completely abandoned and destroyed, amounting to a true crime against architecture.

Major works

Hotel Megas Alexandros

Megas Alexandros & Baggeion: Built simultaneously to Ziller’s designs in Omonia Square at the end of the 19th century.

“Baggeion” and “Megas Alexandros”, almost like twin brothers, were built at nearly the same time according to plans by Ziller at the end of the 19th century. Two imposing masterpieces on Omonia Square, visually connected by the deep red stripes on the upper floors. The “Megas Alexandros” was originally intended as the residence of the landowner Ioannis Bakas. It was designed as a two-story building with statues on the roofline that captivated passersby.

Stathatos Mansion

One of the most significant examples of 19th-century neoclassical architecture in Athens. Construction began in 1895 as the residence of the affluent family of Othon and Athena Stathatos, who owned it until 1938. In 1991, it was granted to the Museum of Cycladic Art, and in 2001, the concession was renewed for another 50 years to the N.P. Goulandris Foundation.

Presidential Mansion

Initially built on the order of King George I as a palace for the heirs to the throne between 1891 and 1897, with designs by Ziller. Since Princess Sophia requested a building with the character of a private mansion, it resembles more the grand residences of the era rather than a royal palace: a three-story neoclassical building with a simple, austere façade, its only projection being the Ionic-style portico at the main entrance. Today it houses the Presidency of the Hellenic Republic and serves as the official residence of the head of state.

Heinrich Schliemann Mansion (Ilion Melathron)

The Ilion Melathron, also known as the Schliemann Mansion, is a neoclassical building in central Athens on Panepistimiou Street. Ziller designed it in 1878 as the residence of Heinrich Schliemann, the archaeologist who discovered the treasure of ancient Troy. The freedom granted to the German architect led to one of the most iconic buildings of Athens at the time. Its construction was completed in 1881. Today it houses the Numismatic Museum of Athens.

Academy of Athens

Built thanks to a major donation from Simon Sinas and initially known as the “Sinaean Academy.” It was designed by Hansen, laid down in 1859, completed in 1885 by Ziller, and officially inaugurated in 1887.

National Theatre

About 250 meters from Omonia Square, it was completed in 1901 according to plans by Ziller to meet the capital’s need for a permanent theatre. The project began as an initiative of King George I and was completed thanks to donations from many wealthy Greeks, mainly expatriates, such as the Rallis, Korgialenios, and Eugenidis families. Despite the difficulties Ziller faced due to the sloping terrain and the small plot, he ultimately delivered a grand eclectic building associated with the greatest moments of modern Greek theatre, highly popular with the public.

Ziller-Loverdos Mansion

Ziller designed this neoclassical building in 1882 at 6 Mavromichali Street as his own residence, incorporating high-quality architectural elements such as plaster reliefs, ceiling paintings, and a distinctive Pompeian salon with wonderful murals. The house was sold at auction in 1912, ending up in the hands of banker Dionysios Loverdos. Today it houses the Loverdos Museum, a branch of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, open to the public.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions