Recent demographic data and historical records shed light on a key question: how fair were Greece’s claims in Asia Minor based on population realities.

The Ottoman Empire in 1920: A Multinational Landscape

By 1920, the Ottoman Empire — already crumbling after the First World War — had an estimated population of about 14.3 million people.

Among them were millions of Christians and Jews who had lived under Ottoman rule for centuries, forming a patchwork of ethnic and religious communities across the empire.

The Greek population was particularly significant. According to estimates from Greek, Ottoman, and foreign sources:

- Constantinople (Istanbul): roughly 330,000–350,000 Greeks

- Western Asia Minor & Pontus: around 1.2 to 1.4 million Greeks

- Eastern Thrace: about 260,000–270,000 Greeks

These communities were not isolated minorities — they formed the backbone of trade, education, and culture in many cities.

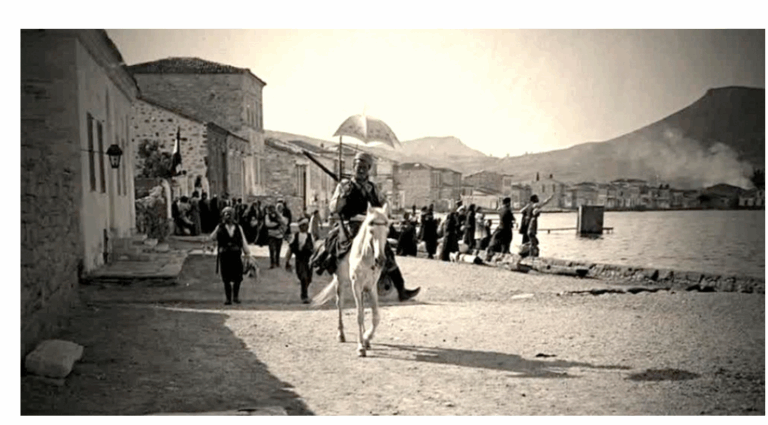

The Ionian Coast: The Beating Heart of Hellenism

Nowhere was the Greek presence more visible than on the western coast of Asia Minor — the region historically known as Ionia.

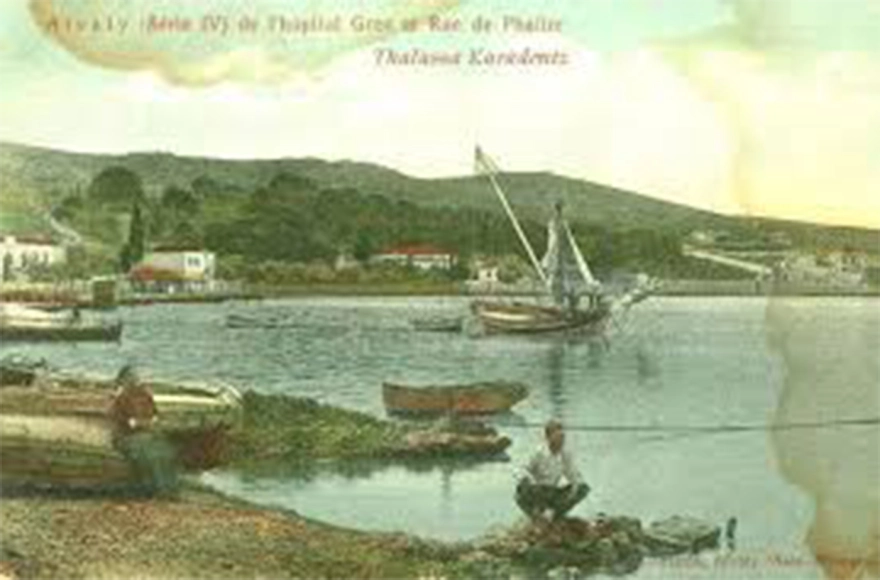

In cities such as Smyrna (Izmir), Aivali (Kydonies), Old Phocaea, and Vourla, Greeks either dominated the population or formed powerful urban majorities.

Smyrna in particular was a cosmopolitan metropolis.

Before the war, it had roughly 600,000 residents, of which around 35–40% were Greek — making it one of the largest Greek urban centers outside the Kingdom of Greece.

The city’s nickname, “Giaour Izmir” (“Infidel Izmir”), coined by Ottoman Muslims, reflected its Christian — largely Greek — character.

Even in surrounding towns and villages, Greek-speaking populations outnumbered Muslims.

This was not a colonial enclave but the living continuation of Hellenic civilization dating back to antiquity.

The Rest of Anatolia: Scattered Greek Communities

Further inland, Greek communities were smaller and more dispersed.

In Cappadocia, thousands of Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians (known later as “Karamanlides”) preserved their faith despite centuries of isolation from the Greek state.

Their existence testified to the deep historical roots of Hellenism throughout Anatolia — even in predominantly Turkish-speaking regions.

From Persecution to Protection: Venizelos and the Asia Minor Campaign

Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, architect of the country’s foreign policy during the Great War, viewed the Asia Minor campaign not as expansionism but as a defensive mission.

Between 1913 and 1918, the Young Turk government had already initiated mass deportations and massacres against non-Muslim minorities, including Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks.

Historical estimates suggest that between 500,000 and 750,000 Greeks were killed, deported, or perished in forced marches during this period.

Entire communities in Thrace, Pontus, and Asia Minor were uprooted.

Venizelos argued that Greece’s occupation of Ionia was necessary to protect the remaining Greek population — and the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) temporarily recognized this by granting Greece administrative control over Smyrna.

A Vision Crushed, a People Destroyed

The dream of a Greek Asia Minor was short-lived.

By 1922, following the defeat of Greek forces and the rise of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Greek population of Asia Minor faced annihilation.

The Great Fire of Smyrna and the ensuing catastrophe of 1922 marked the end of millennia of Greek presence on the Anatolian coast.

What followed was the population exchange of 1923, which formally ended the Greek presence in Asia Minor — turning a once-diverse region into a largely homogeneous Turkish state.

Genocide or Imperialism? Revisiting the Debate

The original ProtoThema.gr article argues that the Greek campaign was not imperialist, but rather a response to ongoing persecution and a final attempt to safeguard Hellenism in its ancestral lands.

It denounces claims of “Greek imperialism” as ignorant or politically motivated, and stresses that Greece has never received international recognition for the genocide of the Greeks of Asia Minor and Pontus.

While historians continue to debate the motives and consequences of Greece’s actions, the demographic evidence remains clear:

in 1919, large parts of western Asia Minor — especially Smyrna and its surroundings — were home to vibrant Greek communities that had existed long before the modern Turkish Republic.

The Lost Mosaic of Asia Minor

As geographer Pantelis M. Kontogiannis noted, Asia Minor in 1921 was home to a rich blend of peoples — Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Kurds, Jews, Levantines, Circassians, and others.

The disappearance of this mosaic after 1923 marked not just a geopolitical shift, but the tragic end of one of the oldest diasporas in human history.

Legacy

A century later, the Asia Minor Catastrophe still defines Greek collective memory.

It remains both a story of national tragedy and cultural endurance, reminding Greeks and Turks alike of the high human cost of nationalism and empire in the 20th century.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions