We have extensively referred to Georgios Kastriotis (or Skanderbeg) in our article on 05/05/2018, which sparked intense discussions. We know that Kastriotis is the national hero of Albania. However, there are still some unclear elements about his origin. A very interesting study by Mr. Paschalis Androudis, Assistant Professor of Byzantine and Islamic Archaeology and Art, at the Department of History and Archaeology of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, on the so-called “Tower of the Albanian” on Mount Athos and the relationship of Georgios’s father, Ioannis Kastriotis, and one of his brothers with the Athos Peninsula, led us to revisit the subject.

We sincerely thank Mr. Androudis for giving us permission to draw information from his study and the additional details he provided.

Ioannis Kastriotis: the father of “Skanderbeg”

Georgios Kastriotis (1404 or 1405–1468) was the son of Ioannis Kastriotis, a feudal lord of present-day northern Albania, and Vojsava, who came from the Serbian noble family of Branković. Silvius Aeneas (the literary pseudonym of Pope Pius II, 1405–1464), a contemporary of Kastriotis, considered the Kastriotis family to be Macedonians from Imathia (a related publication by the late Achilleas G. Lazarou, titled “Albania,” exists in “Nea Estia,” Christmas 1994). Almost everywhere it is mentioned that Georgios’s grandfather, Konstantinos, who died in 1390, was ruler of Imathia and Kastoria, from which the family name derives (Kastriotis < Kastoriotis). His father Ioannis was the ruler of Krujë (or Kroia).

It is indisputable that the Kastriotis family were Christians by religion. Ioannis Kastriotis (1380–1437), initially a vassal of the Ottomans, then of the Venetians, and later again of the Ottomans, extended his dominion as far as Alessio, today’s Lezhe, and the mouth of the Mati River, reaching the sea. Bribed by the Venetians, he joined them. However, Sultan Murad I, in a new campaign in the western Balkans, once again made Kastriotis his vassal. To prevent further disloyalty, he forced him to send his four sons Stanislaus, Reposio, Konstantinos, and Georgios to Adrianople, then the Ottoman capital, as hostages.

Ioannis Kastriotis and Vojsava had nine children (five daughters, whose names are mostly unknown except for Mara, and the four sons mentioned). Murad, appreciating Georgios’s bravery, cleverness, and beauty, personally took interest in his upbringing. Kastriotis was trained alongside the heir to the throne, Mehmed II, also known as the Conqueror. At a very young age, Murad appointed him commander in a battle against the Serbs. Georgios displayed great valor and led the army to victory. Murad expressed his admiration by naming him Iskender Bey (Skanderbeg), meaning “Lord Alexander.” It should be noted that both Georgios and his brothers had converted to Islam. Some events, however, began to shake Georgios.

The mysterious death of two of his brothers (the third, Reposio, became a monk, as we will see in detail later), the appointment of a non-believer, Hasan Bey Versezenda, by Murad as governor of Krujë, who exiled his mother—who died shortly thereafter (his father had died in 1437)—and his nostalgia for his homeland, eventually led Georgios Kastriotis to leave the Ottoman ranks during a battle with the Hungarian ruler John Hunyadi in 1443. After forcing the sultan’s secretary to sign a firman for the surrender of Krujë, he headed with 300 trusted men to his homeland. Seeing the firman, the governor of Krujë surrendered the fortress. The next day the city was filled with banners with Kastriotis’s emblem, the double-headed eagle. The people erupted in cheers. On November 28, 1443, Kastriotis started the revolt against the Ottomans. Kastriotis (see also the article of 05/05/2018) became a nightmare for the Ottomans.

He lost only one battle, to Evren Bey, who had a very strong army of 40,000 men, on July 26, 1455. He went to Italy to seek assistance, but achieved nothing significant. He married the youngest of the eight daughters of the Arvanite Georgios Komnenos, a ruler who also fought the Ottomans. He was offered to lead a crusade, as he had been baptized as a Christian again and seemed willing, but he fell ill from malaria and died in January 1467 at Alessio and was buried in the Church of Saint Nicholas of the city.

How “Albanian” was Kastriotis?

We will now pose some questions about the origin of Kastriotis, who has been declared a national hero of Albania because he was born and acted mainly in what is now Albanian territory.

Is the surname Kastriotis Albanian? And if so, what is its etymology?

How many know that his activities reached present-day Pogoni? Ruins of a fortress still exist in Oreokastro. This fortress was only captured by the Turks when they cut off its water supply from the nearby Gormo River (one of the original streams of the Kalamas).

Is the double-headed eagle, Kastriotis’s emblem, of Byzantine origin or not? (See our related article of 26/06/2021).

What was the official language in the areas Kastriotis controlled? Maria Michail-Dede, in her work “The Greek Arvanites,” writes: “… The same applies to the Arvanites who came down (to Greece) after the fall of Kastriotis, who is known not only to have been Greek, but also to have had Greek as the official language of his state.”

Ioannis Touloumakos, in a speech published in the proceedings of the Second Panhellenic Scientific Conference, titled “The Ancient Greek Cities of Northern Epirus,” writes: “… (Kastriotis) used the name of Alexander the Great and often wore the ancient Macedonian helmet with double horns, while simultaneously presenting himself as a descendant of the Epirotes (specifically of Pyrrhus).”

Kastriotis’s lieutenant was a relative named Vranas, a surname of a notable Byzantine family.

Why is there no popular Albanian (folk) song about Kastriotis’s heroism, while there are songs for lesser heroes?

Was there an Albanian national consciousness in the mid-15th century? At that time, the Albanians were a collection of warring tribes, without national tradition, without national and linguistic unity.

Is it true that when Kastriotis returned to Krujë, he told his Muslim compatriots to choose between Christianity and death, and since most refused to convert, they were slaughtered? The notorious Fan Noli considers this action of Kastriotis a holy war against Muslims.

According to the French journalist and writer René Piot, Greeks also participated in Kastriotis’s wars. For example, the Himariotes, with flags that had a blue-and-white cross. In the defense of Krujë, the clans of Androutsos, Botsaris, etc., participated. As D.N. Botsaris writes: “… after the death of Skanderbeg, the Botsaris, fighting against the Turks and Turco-Albanians, went to Dragani. At the beginning of the 17th century, they, along with other free Greeks, founded the Souliotic Confederation.”

The defenders of Messolonghi (1825) considered Kastriotis a model hero, which is why they named one of their artillery positions, the third in order after those of Drakoulis (actor and fighter of 1821, killed at Dragatsani) and Kanaris, “Skanderbeg.” Some will say these were Albanians who liberated Greece…

Addressing Mehmed II, Kastriotis wrote: “Georgios Kastriotis, renamed Skanderbeg, ruler of the Epirotes and Albanians, soldier of Jesus Christ to Mehmed, the monarch of the Muslims, greetings… 30 May 1461.”

Murad II, in his reply to Kastriotis, calls him “ruler of the Albanians and Epirotes.” Addressing King Alfonso, he calls himself “Prince of the Epirotes,” while to Prince John Antonio of Taranto he writes: “Our ancestors were Epirotes, from whom that Pyrrhus arose… You have no strong men to resist the Epirotes.”

Even on the Albanian stamps issued in 1968 on the 500th anniversary of Kastriotis’s death, his name appears as Gjergi Kastrioti (on the 25 quintar stamp), while another stamp shows the cover of the history by his first biographer, Barletii, titled: “HISTORIA DE VITA ET GESTIS SCANDERBERGI EPIROTARUM PRINCIPIS” (“History of the Life and Deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes”).

Finally, the great historian Pavlos Karolidis went to Italy and met Kastriotis’s descendants. They call themselves Greeks, are devout Orthodox, and their main center in Sicily is called Piana de Greci (Place of the Greeks).

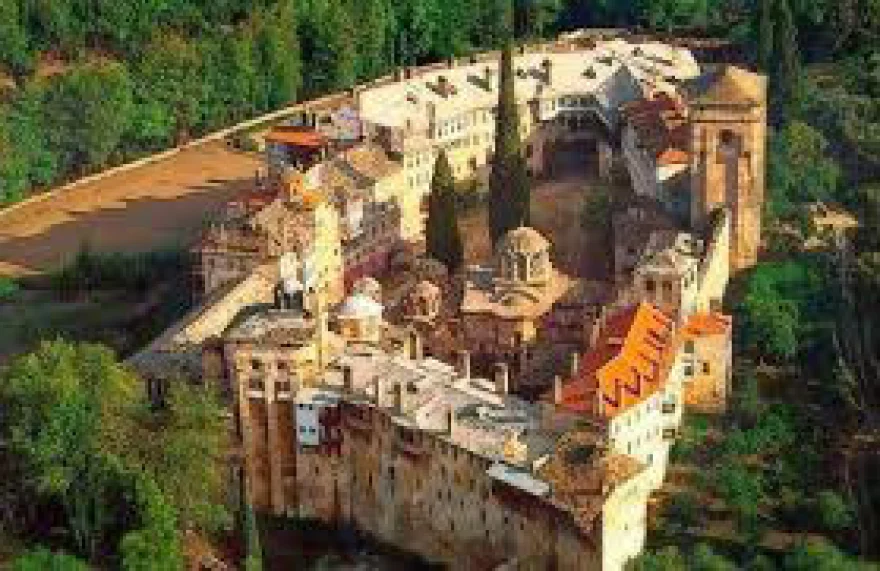

At Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos, Kastriotis’s father and brother are buried! What is the “Tower of the Albanian”?

The reason we revisited Georgios Kastriotis was finding an article online about the “Tower of the Albanian” on Mount Athos. This article is based on an extensive, excellent study by Assistant Professor Paschalis Androudis. We contacted him, and he kindly shared some information.

In the journal “Byzantina” (2002, pp. 219–245), there is an extensive study by P. Androudis titled: “Historical and Archaeological Testimonies for the ‘Tower of the Albanian’ on Mount Athos.”

There we read that at the Serbian Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos, Reposio or Repos, “Duke of Illyria,” died as a simple monk at Hilandar in 1430. He was probably Georgios Kastriotis’s brother, who until recently was thought to have become a monk on Sinai. Repos is presumably the brother who escaped the Ottomans.

As Androudis writes, another relative of Repos also became a monk and was buried at Hilandar. This was probably Ioannis Kastriotis, Georgios’s father, who became a monk on Athos in his last years.

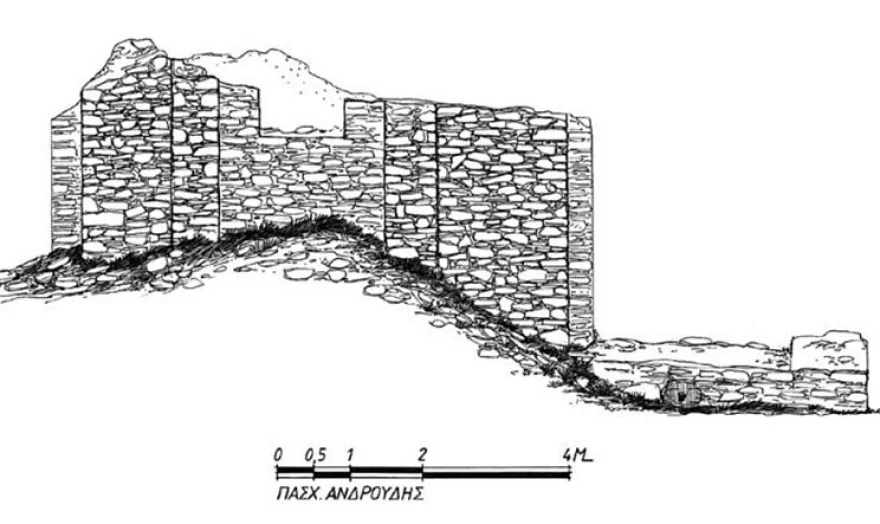

Father and son are buried in an arcosolium, a type of domed tomb. Ioannis Kastriotis is also connected to the “Tower of the Albanian.” It is a partially ruined tower in the wooded area south of Hilandar Monastery, above the abandoned skete of the Holy Trinity. The tower was probably built in the 12th century (according to another version in 1270 on the site of the old monastery of Saint George) and served as a defensive fortress against pirate raids. It has buttresses on each side, revealing Byzantine architectural style. Its preserved height today reaches 6 meters.

According to a document from 1421–1422, Ioannis Kastriotis purchased the tower from Hilandar Monastery for 60 Venetian florins. He also purchased four adelphates for himself and three of his sons. An “adelphate” was the right to reside in a monastery dependency on Mount Athos, accompanied by the right to exploit surrounding farmland. Repos lived for some years in the Tower of the Albanian. There is, however, a problem with dates. In 1423, Ioannis Kastriotis had to send his four sons to Adrianople. When did Repos live on Athos? He died in 1430. Did he escape from the Ottoman capital and go to Mount Athos? In 1468, as there was no hereditary right to the Tower when all entitled adelphates holders died, the Tower of the Albanian (arbanaskii pirg) or Tower of Saint George was returned to Hilandar Monastery.

Later, a monastic community settled there for several years, receiving generous grants from the rulers of Wallachia at least until 1528. In a 1757 engraving, Hilandar Monastery is depicted with the Tower of the Albanian, showing monks residing there. It is unknown when the tower was abandoned. The skete of the Holy Trinity was abandoned in the early 20th century. At that time, or earlier, the Tower of the Albanian was most likely also abandoned… The name was first used in 1512. Until then, it was called the Tower of Saint George.

Conclusion

As mentioned, Georgios Kastriotis was buried in the Church of Saint Nicholas at Alessio. In 1474, Mehmed II captured the city. He ordered Kastriotis’s tomb to be opened but the skeleton not to be disturbed or desecrated. However, the Turks, attributing magical or miraculous properties to his bones, broke them and took a piece each as a talisman. His helmet, however, survived and is kept in a museum in Vienna. This raises the question: could the arcosolium at Hilandar Monastery hide a secret that some Albanian historians have identified?

Sources:

- Sarantos I. Kargakos, “ALBANIANS – ARVANITES – GREEKS,” 6th edition, I. Sideris Editions, 2008.

- Spyros Stoupis, “EPIROTES AND ALBANIANS,” Foundation for Northern Epirus Research, Ioannina, 1976.

- Titos P. Giohala, “GEORGIOS KASTRIOTIS – SKANDERBEG,” Dodoni Editions, 1994.

- And, of course, studies by Assistant Professor Paschalis Androudis of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, whom we sincerely thank for his invaluable assistance.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions