When Turkish officials were scrambling to resolve an escalating dispute with the US, their Nato ally this month, they had a plan.

They had already been informed that Washington intended to cut off new visa applications inside Turkey, a retaliation for the arrest of an employee just days earlier. In the Turkish foreign ministry, the news set off a flurry of phone calls, both formal and informal conversations with diplomats from the US and other countries.

Top bureaucrats started drafting a measured response, including a statement that was designed to help lower temperatures, while they probed their colleagues in other ministries to see how some of Washington’s demands — which included access to the arrested Turkish foreign service employee, and greater clarity about the charges — could be quietly met.

“If handled properly, this could have been a small, one-week mini-crisis,” said a person involved, who asked not to be identified discussing official matters.

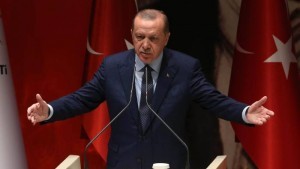

Instead, they got a phone call. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan saw the US statement suspending visa services, and decided upon a response — it would be a near facsimile of the American wording, simply transposing the words “Turkey” and “US”. Ankara’s retaliation was also tit-for-tat — the two allies had overnight placed a near-complete halt on their citizens’ travel to each other’s countries.

It was an escalation that Turkey’s neighbours and friends have grown accustomed to: muscular, often improvised and always provocative. Aided by his combative foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, Mr Erdogan has picked fights with the EU, US, Russia, Syria and most of the Gulf countries. Old friends have been discarded, while old rivals have been cautiously welcomed, as in the case of Israel.

But the speed — and volume — of these diplomatic spats has stretched the limits of Ankara’s professional diplomatic corps that must pick up the pieces after Mr Erdogan has spoken, according to several people, including ambassadors, involved in Turkish diplomacy. It has frayed the relationships between them and their western counterparts, who rarely have access to Mr Erdogan’s aides, and are forced to liaise with officials who are not involved in decision-making, said four western diplomats.

“The general efforts of our foreign policy establishment is directed towards damage control,” said Ilter Turan, a professor of international relations at Bilgi University in Istanbul. “What we are seeing is a foreign policy that’s based on daily events, and domestic foreign policy needs, and therefore, it is unpredictable.”

The problems have been exacerbated since Ankara imposed a sweeping crackdown in the wake of a coup attempt last year in which more than 140,000 people have been arrested, dismissed or suspended for having alleged links to Fethullah Gulen, the US-based cleric Mr Erdogan blames for the failed putsch. The president has been angered by Washington’s refusal to extradite Mr Gulen and Europe’s criticism of his human rights record.

At least two dozen Americans and Europeans, including dual nationals, are among those detained. The increasing perception in western capitals that the detentions are politically motivated and are to be use as bargaining chips has further strained relations.

“Increasingly, I have told my government that I have no reliable counterparty to discuss anything with,” said one EU diplomat.

EU diplomats point to an incident in March when Mr Erdogan drew support from Turkish nationalists by accusing German chancellor Angela Merkel and the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte of “Nazi-like” behaviour. That was after authorities had denied permission for Mr Cavusoglu to address a crowd of Turks in Amsterdam during the Dutch election campaign.

As the crisis brewed, European officials received assurances from Turkish officials, including prime minister Binali Yildirim, that the situation would be resolved calmly, only to see Mr Erdogan repeat his comments.

“That was very telling — the Dutch PM and the Turkish PM made a late-night agreement, and by the time they woke up, the president had already violated it,” said a diplomat from a Gulf nation.

For the EU, which will decide at a summit this week whether to punish Mr Erdogan for his increasing authoritarianism — including the arrest up to 11 Germans in the last year — by cutting off hundreds of millions of euros of pre-accession funding, the problem is acute.

The ructions come as Ankara warms relations with eastern partners, including Russia and Iran, with Mr Erdogan’s main concerns being US support for Syrian Kurdish militia and the influence of Gulenists in Europe.

Asli Aydintasbas, a Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations says that is because the west is still trying to negotiate with Turkey under an obsolete model — one where Ankara is seeking closer engagement with the EU.

“You can’t talk to Turkey in the way that you have been, and certainly not in the framework of the EU accession project — that is not going to work, because Turkey is not in that framework any more,” she said.

The end result is that decades-long relationships are no longer able to support a fraying alliance.

“For many years, while there were public problems and fights, in private, we could still make things work — the relationships were there, the goodwill was there, the patience was there,” said a retired Turkish diplomat who worked closely with Brussels. “Now, there is a sense that there is a break of some sort.”

Source: ft.com

Ask me anything

Explore related questions