A chilling video first released in the 1940s appears to show Soviet scientists attaching a dead dog’s dismembered head to a machine and bringing it to life.

Footage reportedly from the Soviet Film Agency shows several Soviet scientists attaching the head of a dog to a machine.

The machine appears to be able to circulate blood around the brain and restore basic motor functions to the head.

And later in the footage, the same scientists use the technique to revive a dog that had been clinically dead for at least ten minutes.

The footage, released just a year before America’s entry into the Second World War in 1941, was shown courtesy of the National Council of American-Soviet friendship.

The first part of the film, which took place in 1928, shows the experiments of Soviet scientist Sergei Sergeevich Brukhonenko, who created an apparatus for the artificial circulation with blood of warm-blooded animal.

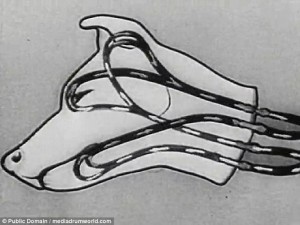

The device was named ‘autojector’ and consisted of two mechanically operated diaphragm pumps with a system of valves.

Those present at one of the first demonstrations of the technology to Soviet leaders reported that ‘the isolated head reacted briskly to the environment, opened its mouth, and even swallowed a piece of cheese placed in it.’

‘The isolated head lives on for hours, and even reacts to external stimuli,’ the film’s narrator notes.

‘The head even reacts to light, and to sound.

‘And, the revival of individual organs allowed scientists to proceed with experiments on reviving the whole organism.’

The experiment was also demonstrated to A. V. Lunacharsky, Russian Minister of Education, and to several international scientists, among them Professor Haldane from the United Kingdom.

The news of the head surviving after being cut off from the rest of the body spread quickly through Europe, and by 1937 Brukhonenko had perfected his heart and lung machine.

In 1939, it was reported that 12 out of 13 experimental animals were resuscitated using the heart-lung machine after ten minutes of circulatory arrest, one of which can be seen in the video.

All dogs were reported to have recovered completely without any residual neurological damage.

The idea of extracorporeal circulation began in 1813 when Julian LeGallois suggested the body could be kept alive by artificial circulation.

It was not until Brukhonenko’s first experiments in the 1920s that the possibility of keeping blood flowing around the body after the heart was removed was fully established.

In 1928 he applied for a patent on his ‘Device for Artificial Circulation’ and between 1929 to 37 it was used in open heart operations for dogs.

This device meant that blood could still pump around the body while the heart was removed.

It consisted of two parts – an oxgenator to saturate the blood with oxygen and removed excess carbon dioxide, and a pump.

The pump drew used blood from the hear and deposited it in a glass chamber. It was warmed, oxygenated and then pumped back into the animal.

The pump was not hermetically sealed and eventually the blood would coagulate. However, he was able to keep a dog’s head alive for one hundred minutes.

In 1929 when Bryukhonenko was working on dog’s heads, Aleksei Kuliabko of the Physiological Laboratory of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg and ‘chemico-pharmacist’ Fyodor Andreyev made a dead man’s heart beat for twenty minutes.

The man’s heart heaved and he choked violently, reports suggested.

In 1934 Bryukhonenko tried to revive a man who had committed suicide just three hours earlier.

The dead man’s body slowly warmed and his eyelids fluttered but the reanimation lasted just two minutes as the experimenters turned off the pumps.

The scientists were ‘unbearably horrified’ by what they had done, writes Salon, and after that Bryukhonenko only experimented with dogs.

Bryukhonenko’s device was never used in a clinical open heart surgery and a newer version created in the mid-1950s by John Gibbon overshadowed the work of Brukhonenko.

Modern devices are based on the same principles but are now much more complex and also control the chemical composition and temperature of the blood flowing into the body.

There is some dispute as to the validity of the video, with some claiming that the film was a propaganda effort by the Americans and the British to make the Soviets appear formidable to the Nazis they were fighting.

It is probable, though, that the film is genuine, given that experiments such as this would not have been impossible in the 1930s and 1940s.

Scientists haven’t given up hope of bring dead bodies back to life in this way.

Nearly 100 years after Brukhonenko’s initial experiments, a controversial neurosurgeon is planning to reanimate human corpses in new ‘Frankenstein’ experiments.

Dr Sergio Canavero, director of the Turin Advanced Neuromodulation Group, and his collaborators believe they may be the first to conduct a human head transplant.

They have outlined plans to test whether it is possible to reconnect the spinal cord of a head to another body with tests that will stimulate the nervous system in fresh human corpses with electrical pulses.

The aim of the surgery is to first cut the spinal cord and then repair it before using electrical or magnetic stimulation to ‘reanimate’ the nerves and even movement in the corpse.

In an article for the Surgical Neurology International, Dr Canavero and his colleague in South Korea and China drew parallels to the infamous story of Frankenstein, where electricity is used to reanimate the fictional monster.

Source: dailymail.co.uk

Ask me anything

Explore related questions