Technology can reach as far as Plato’s tomb, enter its imposing gardens, and unveil details of his life with precision. Thanks to a new method of papyrus reading, Italian researchers not only pinpoint the location where the ancient philosopher seems to be buried but also provide valuable information about his life. For instance, it’s revealed that he wasn’t sold into slavery upon his return from Syracuse, Sicily, as previously thought (which was around 387 BCE), but rather in 404 BCE. However, Italian scientists who studied the damaged papyri agree with the scant evidence suggesting that the philosopher passed away at an old age – over 80 years old – and that he’s buried in the broader area of the Academy, which, following this tremendous discovery, is now accurately located in the gardens of the school founded by the philosopher and renowned worldwide.

The Significance of the Remarkable Discovery

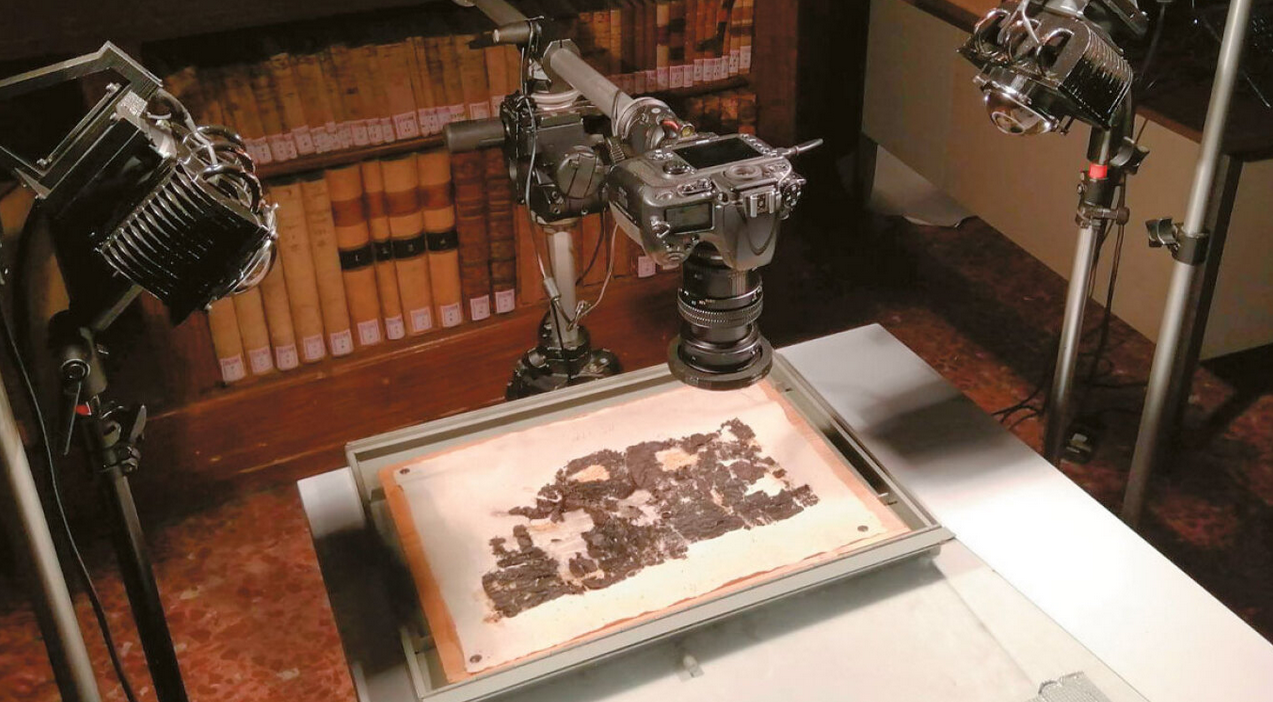

For years, researchers have been attempting to decode the papyri destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE using the famous “bionic eye.” Its advanced application, compared to its previous use in the 1990s, aided in identifying even more words and compiling a rudimentary text. According to the papyrus text, the clear information is now given that “Plato was buried,” and through research led by the Italian papyrologist Gratziano Ranocchia, it is clarified that the philosopher was buried at his Academy – specifically in the gardens near the Temple of the Muses.

(The Italian papyrologist Graziano Ranocchia)

We know from the Alexandrian Eratosthenes, who provides us with dates of birth and death of Plato, as well as from various references, primarily from Neoplatonic philosophers like Olympiodorus, who wrote Plato’s biography in the 6th century AD. Valuable, albeit not entirely reliable, is the biography of Plato by Apuleius that preceded it, while undoubtedly credible is that of Diogenes Laërtius with his “Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.” According to these sources, we know that at the Academy, Philosophy, Dialectics, and Mathematics were definitely taught, and that at the entrance there was the famous inscription stating that no one ignorant of Mathematics and Geometry could enter (“Let no one unversed in Geometry enter”).

There are numerous references to texts by other historical philosophers, such as Cicero, Friedrich Nietzsche, the contemporary scholar Eric Voegelin, Plato’s biographer Alfred Edward Taylor, Michael Frede, as well as the academic Simon Critchley.

With today’s papyri and the new method of the “bionic eye” that managed to read a 1,000-word text, we extract valuable information not only about the death but also about the overall life of Plato. These are papyri and texts that originate from the famous library of the Epicurean philosopher Piso (full name Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus), the father-in-law of Julius Caesar and one of the most eminent thinkers of the time, who held many different offices: from treasurer to praetor, consul, and even proconsul in the Roman province of Macedonia.

(According to Italian researchers, the philosopher was buried at the Academy – specifically in the gardens near the Temple of the Muses)

However, the most important thing was that Piso was the owner of the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, where a library of priceless scrolls was rescued, providing countless information about Epicurean and Neoplatonic philosophy, about the life and days of the philosophers who supported it. It is said that Cicero’s texts, from which we have gathered information about the life and death of Plato, his surviving rhetorical speeches, and his correspondence, are directly linked to the scrolls in Herculaneum. In this library, we find a total of over 1,800 papyri with philosophical texts, mainly by Philodemus of Gadara – whose patron was Piso – most of which are preserved in the National Library of Naples and are not exhibited to the public because they are considered particularly “sensitive” archaeological finds. So far, 340 scrolls have been deciphered, with 970 considered partially damaged, while about 500 are charred fragments. As can be perceived, these are valuable treasures and an inexhaustible source of information about Ancient Greece and its philosophers.

Ban on private cars movement on weekends?

What do we know about Plato’s death?

Although the information Plato offers about Athens of his time through his monumental dialogues is endless, revealing his political beliefs and philosophical positions, he himself does not reveal much about himself or his personal life. An exception might be the Socratic “Apology”, where faced with the turmoil caused by the trial and the impending death of his teacher, he appears as one of the friends-disciples of Socrates who urge him to request an increase in the fine from one mina to thirty. A similar reference is found in the wonderful dialogue “Phaedo”, where Plato almost apologizes for not being able to be present near his great teacher during his last moments, as he was unwell. Certainly, most of those who took care to provide information about the life and work of Plato were the Neoplatonic philosophers like Piso. Great discussion has been made about the information about the philosopher’s life provided by the famous Platonic letters, including the well-known “Seventh Letter”, which reveals Plato’s personality in his own words, as he is said to narrate a part of the story of his life, explaining the reasons why he preferred philosophy to politics, as much discussion has been made about whether he himself wanted to apply the principles of the “Republic” in Sicily.

However, contemporary scholars specializing in Plato, such as the unforgettable Miles Burnyeat and Michael Frede, tore apart their Platonic garments by highlighting that the letter was fake as it did not include anything of the known, refined, ironic Socratic style that identified with that of Plato in the early dialogues, not even the deeply philosophical one of the later ones. However, the biographer Alfred Edward Taylor in his extensive biography of Plato (available in Greek by the MIET) insists that the letter was genuine and that it offers us valuable evidence about his adventures in Syracuse. What is certain is that Plato wanted to apply his political plans in Syracuse after the meeting he had with Dionysius the Younger in 367 BCE, shortly before his rise to power, following the intervention of his advisor Dion, who had met Plato in Athens and had attended his philosophical teachings.

This friendship, however, aroused the suspicions of the suspicious Dionysius, who began to suspect a conspiracy between the two friends against him, leading to Plato being initially imprisoned and then expelled to Athens. Returning to the Ionian capital, the philosopher once again took over the direction of his Academy, and these details are offered to us by the “Thirteenth Letter,” which is supposed to be a personal message sent by Plato to Dionysius. What is certain is that after these adventures, Plato ended up as a slave in the Spartan-occupied Aegina in 404 BCE, something that is now confirmed by the invaluable papyrus “read” by Ranokia.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions