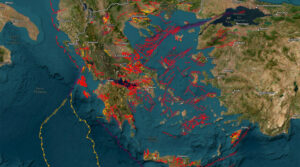

A digital map with all the faults of Greece and their characteristics, prepared over the last two years by the Hellenic Authority for Geological and Mineral Exploration (EAGME) with data from the Geodynamic Institute, the Universities of Athens, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and Patras and the National Research Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, under the supervision/coordination of OASP (Organisation for Earthquake Planning and Protection), is now in the air.

The map, according to Kathimerini, currently has 5,500 entries in Greece. “Attention this number is not the same as the number of faults because for example a 40,000-kilometre fault may have 10 recordings”.

On the map, which anyone can visit at activefaults.eagme.gr, faults in red, yellow and purple are distinguished. In broad strokes, the so-called “seismic faults” are shown in purple, i.e. those that have been proven to be associated with one or more earthquakes in the instrumental or historical period (they are the most “dangerous”), while the “active faults” are shown in red, i.e. those that have been displaced at least once during the Upper Pleistocene (the last 126.000 years or so) and therefore may be a source of future earthquakes, and in yellow the ‘potentially active faults’, those that have characteristics reminiscent of active faults (they have been active at least once during the Quaternary, in the last 2 600 000 years), and in yellow the ‘potentially active faults’, those that have characteristics reminiscent of active faults (they have been active at least once during the Quaternary, in the last 2 600 000 years).

“To date, systematic work has been done and several active faults have been discovered,” says Kostas Papazachos, professor of Lithosphere Physics, Seismology & Applied Geophysics at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. “OASP took the initiative to systematize this knowledge and develop it. This database is a first attempt to see on a map what we know and what we don’t know.” As explained, the map will be dynamic, constantly updated and enriched.

The map will not only be consulted by seismologists, however. “It is of great importance that the database is accessed by civil engineers, urban planners, municipalities who need this information for all kinds of studies. It is not possible to place a high-risk project on an active fault, that is, a fault that has given or may give earthquakes in the coming period. If, for example, a landfill site were to be placed on such a site, it would be bad practice, as there is a possibility that the layer that prevents the waste from going into the deeper layers of the soil could be broken. Similarly, it is not possible to build a hospital there. The database is certainly useful for the development of seismic policy.

Despite continuous research, many of the active faults are still not known. “The big faults are in (on the map). But the smaller ones, especially those in the marine area are a problem, because many do not reach the surface. The marine area is very difficult to survey. There are areas with huge gaps and unfortunately, with the crisis, the scientists who would have studied all this have left Greece.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions