“Rise, my soul, give power / Set your clothes on fire / Set your instruments on fire / So that our terrible voice may burst forth like a dark spirit”:

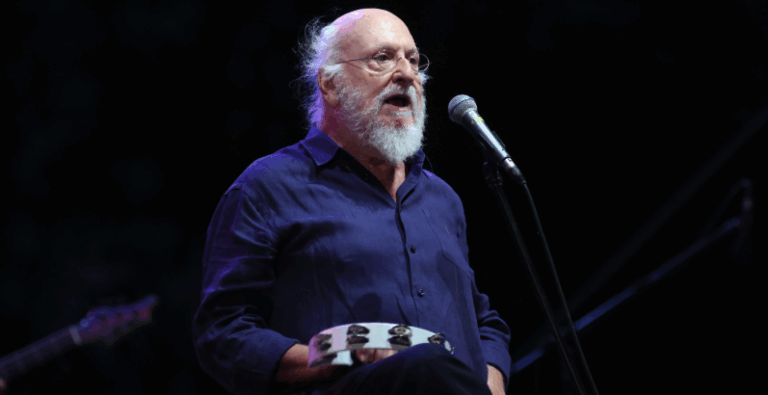

as if we can still hear the thunderous voice of Dionysis Savvopoulos echoing from above — a voice that never ceased to stir us, to challenge us, to accompany the upheavals, the doubts, the odd wanderings in the garden of our own sky, and the sense of Greekness that he held high — even as he saw deep into all our contradictions.

Born, as he himself used to say, “on the eve of the Civil War,” on December 2, 1944, he did not come into a war-torn Greece to submit to fate, but to overcome it — or rather, to shape a different course for all of us, guided by his songs.

From a young age, lying in his teenage bed in a Thessaloniki neighborhood, Nionios (as he was affectionately called) would make up verses — just as he did when he fell in love, when he felt despair in detention during the Junta years, or later in the army, where, to keep from going mad, he translated Bob Dylan’s “Wicked Messenger,” turning it into the now-famous Greek song “Aggelos-Exaggelos” (Angel-Messenger).

All his songs balance between harsh reality and dreamlike imagination.

They serve as guides through a strange geography that embraces rock and Tsitsanis, folk and island music, electronic sounds and the most melodic verses.

It is the Greece he managed to envision — even before the country passed through its most turbulent post-war years — a Greece with “windblown castles, boats in the light,” with fireworks, choirs, and “crowds seeing visions.”

If someone asked him where he found the strength to endure, he would probably say it was in his power to invent odd worlds, to dance with ballos rhythms, shadow puppets, and countless cloud-gatherers (Nepheligeretes) — to define, as he sang in his autobiographical song “I Was Born in Thessaloniki,” his own paths, like the one he took when he left everything behind and moved to Athens to follow his dream.

He was not yet twenty when he decided — after dropping out of law school in Thessaloniki — to carve his own path.

He knew music was his destiny and did not resist it.

Sleeping wherever he could — on friends’ floors, even in the offices where he and the Bertrand Russell Peace Committee made protest placards — he worked odd jobs, from painter to porter, and even managed to work as a model for the School of Fine Arts.

At the same time, he tried his luck in music, performing at nightclubs and connecting with all the major composers of the era, who quickly recognized his extraordinary talent.

It is the era of uprising and general unrest, and he himself always remains politically engaged—yet never allows any political party to “pull him by the sleeve,” as he would later write in one of his most beautiful songs, “The Loneliness of Alexis Aslanis,” which was sung in the boîtes of the time.

He takes to the streets with the Lambrakis Youth, protests against the Vietnam War, admires Bob Dylan, who becomes his guiding star, and loves Tsitsanis too. He burns for revolution but burns even more for love: because “when evening falls, what can I say / I remember you in your green coat”—and his loves, until he met Aspa, the woman of his life, didn’t always have happy endings.

The 1960s – The First Songs and Recognition

It is the mid-1960s, and songwriter Savvopoulos is beginning to resonate with the restless urban audience. Recognition comes with his first record, released one day after Valentine’s Day 1965—not by chance, since in one of Greece’s most politicized eras, he chose for his debut songs like “Don’t Talk About Love Anymore” and the incomparable “A Small Sea”—a hymn to love, at a time when everyone else was singing manifestos.

In November 1966, To Fortigo (The Truck) is released, based on earlier material but enriched with new songs that signal what is to come.

Between the dilemma of “invincible love” or “political uprising,” he sides with life and love, because he knows that what will remain when everything else fades is the power of moments—what lingers from the dream when everyone else has awakened.

A Poet at Heart

And this is what sets him apart from other songwriters and performers of the New Wave: his understanding that small moments carry far greater weight than sentimental descriptions of eternal feelings.

He embraces the anxiety of Jacques Prévert, who sees life in central Paris as a living carnival passing by; he listens to the irony of Georges Brassens; he prefers Hadjidakis’ humor to Theodorakis’ revolutionary fervor.

Deep down, he knows he is a poet, and this defining belief guides his life—like a muse leading him through the fog of the highway, like a blind Homer nodding to him through the mist of history.

“Thanks to words,” he writes in his autobiographical book Why the Years Run Wild, “I lived a second life—a parallel life, often more real than this one.”

Exile, Love, and Return

His autobiography, recently published by Patakis, was not written to recount his career but as a farewell gift, commemorating the poets of his heart, his old loves, and even himself as a restless child on Fokionos Negri and Patission Street, confessing that he always changed—because he always tested whether he could withstand the various roles he adopted throughout his life.

During the Junta, unable to bear censorship and repeated interrogations, he contemplates leaving for the City of Light.

In Paris, away from Greece, he writes in his favorite haunt, Saint-Claude, the famous “Ode to Che Guevara,” which he disguises as “Ode to Karaiskakis” to pass censorship.

It’s the same café where he played pinball with the “unbeatable,” as he called him, Alekos Fassianos: “Five months in Paris—I wrote songs and played pinball.”

Depression left him little room for resistance.

He even thought of giving up music and working on ships—but in 1967, meeting Aspa kept him anchored:

“She was so beautiful she glowed at night,” he wrote. “But I was still stumbling—between hashish and disappointments, I didn’t yet understand the role this creature would play in my life.”

Between Karagiozis and Aristophanes

That was Savvopoulos: never a pretender to rebellion, but a true descendant and reimagined heir of François Villon, who loved equally the Greek folk songs and the cunning shadow-puppet hero Karagiozis.

He adored the fairy tales his grandparents told him in Thessaloniki and decided to retell them himself, adapted to his own carnival-like rhythm—our earthy rhythm.

He took drums and zournas, borrowed theatrical techniques and the dreamlike depth of Aristophanes—as seen in his ideal Acharnians, which he dedicated to the “birthplace” of Koun and Hadjidakis—and remained an observer of all our dreams and weaknesses.

He cherished the vivid images of crowds, whether in the streets or in Prévert’s verses, “where the beautiful day pulls the worker by his coat,” which inspired “Red Sun, Chief,” though he had to remove the “red” due to censorship.

That color, later, became the “party pulling at one’s sleeve”—an ironic commentary on the coercion of the Left, which blacklisted him.

Because of that lyric, the Communist Party (KKE) severed ties with him, beginning his rift with the world of the Left.

But he had already pledged himself to Aristophanes and to the fools and dreamers—like Don Quixote, chasing windmills and retreating to his own distant castles.

“Whatever I wrote is a stammer, I think. That’s what music is for me: the divine song that a clumsy child sings, stuttering, holding in his heart the impossible melody of a longing for perfection from a creature that can never reach it.”

From Paris to “The Garden of the Fool”

Nothing in Paris was easy—or possible.

He realized that the city of poets had nothing more to give him as the great demonstrations of May ’68 began.

He decided to leave on the day of de Gaulle’s counter-demonstration, penniless, hitchhiking back to Athens with Aspa, then pregnant with their first son, Kornilios.

They arrived in Athens via Milan, where he began to imagine his next album.

The choice was clear: he had to return to Greece—to the “Garden of the Fool,” as the record he wrote soon after his return (and his son’s birth) would be titled.

With a guitar in his hands and a colorful bird on his head on the psychedelic cover, he entered his boldest, most rock-infused phase.

It was the time of alternative rock, Tasos Falireas, the wild nightlife, and the legendary performances at Kyttaro, where he experimented freely, blending all forms—Karagiozis singing beside him, and filmmaker Lakis Papastathis capturing his visions on film.

Together they saw Theophilos, Karaiskakis, and the living folk tradition—its painting, music, poetry, and imagination.

Yet he also honored the old fighters, for whom he felt deep nostalgia—dedicating “Happy Day” to the days of Makronisos.

From “Rezerva” to “To Kourema”

His masterpiece Rezerva (1979) marked the start of the 1980s with force.

The decade was defined by his return concert at the Palais des Sports in Thessaloniki (1983) and the release of Tavern Tables Outside (Tραπεζάκια Έξω), where Nionios exposed the compromises of the Left in its pursuit of new power.

His songs became anthems for the Rigas Feraios youth, who used them to answer the dogmatism of the Communist path.

The conflicts with the Left were tough—worse were the moments of public disapproval during To Kourema (The Haircut).

As he later wrote:

*“With *To Kourema* I turned toward the Right, worn out by the pseudo-progressivism and arrogance of the time. It was a foggy, unproductive, overly cultured and completely anti-spiritual progressivism. The Left, unfortunately, was swept away by that cheap version. Old leftists—justifiably resentful toward the Right that once humiliated them—when PASOK emerged, they all moved there. PASOK became the refuge of every wounded ego. And its populism was so great that it corrupted the entire political system.”*

A Confession and a Farewell

Despite the conflicts and personal struggles, he never disowned any phase of his life.

In his confessional autobiography, he apologized to those he had wronged—like Thanos Mikroutsikos, and above all, his wife Aspa, for his transgressions.

He spoke honestly about his weaknesses, showing that beneath the colorful personas he remained a vulnerable mortal.

In the final, prophetic chapter of his book—where he imagines himself ill, wetting his pajamas before the tender gaze of a nurse—we glimpse the confession of mortality of a man we still cannot believe is gone.

The raised hands—in joy, in celebration, in prayer—in a strange but unique world he painted with countless images, melodies, and caresses, are the lasting picture we hold from the theater of his life:

“How you dance with your hands raised / as if searching for an invisible ladder / your hips gently swaying / now near, now far / moving through a space where the sun / turns only toward the cistern / and with dark glasses turns again / toward love’s shadowed side.”

Savvopoulos will live forever—through these gestures, through the glorious movements of our own lives, in a world both vast and frighteningly small—but undoubtedly our world.

Only he, after all, understood it better than anyone else.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions