You may approve or disapprove of prostitution as much as you want, but the fact is that ever since the earliest human cultures started to develop, prostitution developed too. As temples, marketplaces, and local customs evolved and thrived in the days of ancient Mesopotamia, so did prostitution. Hence it is sometimes referred to as the world’s oldest profession.

When Sumerian culture established itself in the territory of Mesopotamia, one of the most prominent cults was that of the goddess Inanna, who was known later as Ishtar in other regional cultures. Her figure unquestionably inspired a universal admiration across the entire Middle East. Among other things, she emerged as the patron of prostitutes and public houses, and part of her worship likely included temple prostitution as well.

Many centuries after the heyday of ancient Mesopotamia, prostitution also became part of the society of Ancient Greece, where the word “pornai” meant prostitute; reportedly, it is from this Greek word that we derived the word pornography in the English language.

Prostitution in Ancient Greek society was reasonably accepted, and Athens emerged as one of its foreknown centers, where brothels flourished and attracted not only locals but also foreign travelers, merchants, and sailors who came to the city for business. Beginning from the Archaic period of Athens in between the 8th and the 5th centuries B.C., prostitution lingered well into the Classical era.

(A banquet musician reties her himation -long garment- as her client watches. Tondo from an Attic red-figured cup, c. 490 BC, British Museum)

Like any other occupation, it was required by law that everyone in the business paid taxes on their income, which could mean the status of this profession was perhaps more advanced than it is nowadays in many countries worldwide. Quite often, prostitutes first came in as slaves, or they were foreign women with limited rights but were allowed to make earnings by offering sex services.

Slave women who ended up in the business were frequently able to make enough money so they could buy their freedom. Many also opted to continue with the occupation, as they retained more independence and were not controlled by men, as was the case with married Athenian women.

The pornai had the option to work in brothels, but they were able to offer their services on the streets too. Some records even tell of genuine “advertising” some of the women used. They would put on special sandals that left imprints of the message “follow me” on the ground, in the dirt, as they lured new clients to certain areas of the city.

There were also the higher class prostitutes, called “hetairai,” which translates to “female companion,” and the difference was that the hetairai were well educated with talents in arts. Mostly they were the courtesans of the upper classes. Men prostituted as well, and they were called pornoi. Despite offering their services to women, more often than not, they served other men too, usually of older age.

As prostitution never ceased being a lucrative business both for brothel owners and independent workers, particularly in the case of ancient Athens, this gave a sense of infamy to the city. However, it always gave reasons for travelers to stop at the docks and spend several days there. It meant more cash flow for Athens, which helped the city strengthen its position of influence and power on the shores of the Mediterranean.

It was far from the case that only foreigners were allowed to spend time with prostitutes; married men also went after them, with expectations that their wives would pretend nothing happened. Evidence suggests at least one case where a woman from Athens filed for a divorce from her husband due to his involvement with a prostitute, but her efforts were unsuccessful.

For younger men, it was even more common to visit the infamous zones of the city. Back in those days, Athenian men would rarely step into marriage before the age of 30, by which time many gained sexual experience in the company of prostitutes. More accounts tell that some prostitutes became concubines to younger men, or even their wives. There was one downside in such scenario, though. If a child came out from this type of relationship, it was not counted a citizen.

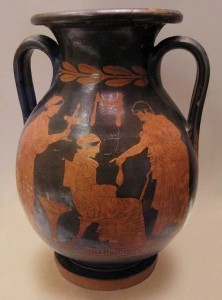

(Courtesan and her client, Attican Pelike with red figures by Polygnotus, c. 430 BCE, National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

Children were in fact one of the biggest downsides of the profession. If women in the business fell pregnant, they were left with two options: to either raise the infant alone or to opt for infanticide, which unfortunately was a common practice.

Perhaps the brighter side of the profession was the independence it allowed, also the certainty of some power, as money always came in. Some women reportedly ran brothels on their own. They were allowed to buy female slaves, train them and offer them jobs, which may have worked well for older women. As the business relied upon beauty and youth, prostitutes were left with fewer options to earn income as they aged, and largely they relied on what their daughters or any of the bought girls cashed in from visitors.

Source: thevintagenews

Ask me anything

Explore related questions