In 1940, members of the British military were slaughtered – after they had surrendered to German forces. Two survived, but no one believed their story. However, before the war ended, some Germans wanted those responsible punished.

It started on May 26, 1940. British and Allied forces in France were retreating from the German onslaught, withdrawing to Dunkirk for evacuation back to Britain. The Germans followed, all expecting the worst.

To everyone’s surprise, however, the Germans did not press their advantage. They stopped for three days – long enough to let the evacuation happen. By the time it ended on June 4, about 330,000 Allied troops had made it out of France.

(British prisoners of war with German tank in France, 1940)

Not all did, though. Less well-remembered were those who fought to buy those evacuees the time they needed.

SS-Obergruppenführer (senior group leader) Theodor Eicke was fanatically loyal to Nazi ideology. He was in charge of the 3rd SS Division Totenkopf – a paramilitary group that shared his views. As a result of their reckless behavior, Totenkopf suffered more casualties than other German forces at the start of WWII.

(Allied troops fleeing Dunkirk in 1940)

On May 24, the Totenkopf had been crossing the La Bassée River on the way to the town of Béthune when they came under fire from the British. To their surprise, they were ordered back across the river as their tanks were needed at Dunkirk.

(The 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment on February 26, 1940, in France receiving their rum rations before patrol duty)

Planes were sent in to attack Allied positions in the town. Two days later, they again crossed the river and drove the British out.

The 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment and the 8th Lancashire Fusiliers were ordered to hold the Allied line at the French villages of Riez du Vinage, Le Cornet Malo, and Le Paradis for as long as they could. For them, there would be neither rescue nor evacuation, and they knew it.

At dawn on May 27, the Totenkopf attacked the British at Le Cornet Malo at the cost of four dead German officers. By the time the British surrendered, some 150 men from both sides lay dead and about 500 were wounded. Le Paradis was next.

(SS-Obersturmbannführer Fritz Knöchlein)

The 2nd Royal Norfolk’s headquarters were about a mile north of Le Paradis, at a farmhouse called Cornet Farm just beside the Paradis Road. Across were the headquarters of the 1st Royal Scots, who also buckled down.

At 11:30 AM, both were told to do the best they could – the very last orders they received. So they dug trenches around their camps and did just that.

Facing them was the 14th Company, 1st Battalion of the 2nd SS Infantry Regiment under SS-Standartenführer (Colonel) Hans Friedemann Götze. The British held their ground until they were forced out of the ruined farmhouse and took shelter in the nearby cowshed. Götze was killed, and the British kept fighting until they ran out of ammo at around 5:15 PM.

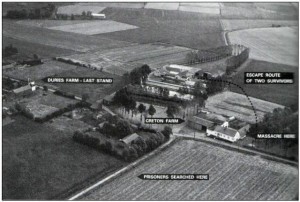

(Scene of the fighting and subsequent massacre)

By then, there were only 99 men left under Major Lisle Ryder. Unable to fight back, Ryder ordered his men to surrender, so they stepped out of the shed with a white flag. The Royal Scots did the same.

In the confusion, they surrendered to different German units. Mass graves discovered in 2007 showed that about 20 Scots had surrendered to the wrong group and paid for it.

Private Robert “Bob” Brown, a signaler with the Royal Norfolk Regiment, was very lucky. Brown gave himself up to a Wehrmacht (regular German military) unit who mercifully took him away before he saw what happened next.

SS-Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Fritz Knöchlein was deputy commander of Totenkopf 3 Company, Group A, 2nd Regiment. He ordered the prisoners stripped of their weapons and marched toward another barn. Beside it were two machine guns manned by the No. 4 Machinegun Company.

Lining the 99 British troops against the wall, he had them shot. Then he ordered his men to bayonet any survivors.

The next day, Gunter d’Alquen, a journalist, reported what he saw but he believed the men had had a trial before their deaths. News spread and General Erich Hoepner, who commanded the German troops in France, tried to have Eicke dismissed. He failed. Other German officers allegedly challenged Knöchlein to a duel, but nothing came of it.

(General Erich Hoepner)

However, not all the British were dead. William O’Callaghan was hit in the arm, the impact throwing him to the ground. Seconds later, another body fell on him, so he played dead. Once the Germans left, he found that Albert Pooley had also survived, albeit with a shattered leg.

O’Callaghan pulled his comrade out then half-dragged and half-carried him to a ditch. It turned out to be a pig sty. The men survived for three days on raw potatoes and muddy water they drank from puddles until they were found by Madame Duquenne-Creton and her son, Victor.

They owned the farm, and despite the risk to themselves, sheltered the men. That ended when the Wehrmacht’s 251 Infantry Division came along and took the men as POWs. Fortunately, the Duquenne-Cretons were spared.

(William O’Callaghan (left) and Albert Pooley arriving at the War Crimes Court in Hamburg)

Pooley had his leg amputated in a Paris hospital while O’Callaghan spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp. In 1943, Pooley was sent back to Britain as he was no longer a threat to Germany.

He told his story to authorities at the Richmond Convalescent Camp, but no one believed him. When the war ended, he visited Le Paradis in September 1946 and was interviewed by the Nord Éclair – a local newspaper. They interviewed locals, who confirmed the story, which angered British authorities.

Why had Pooley not told anyone his story before?! He had but to incompetent and disbelieving bureaucrats. The War Crimes Investigation Unit found Knöchlein, who had returned to civilian life. He was brought to Britain and kept at the London District POW Cage in Kensington Gardens.

(Expanded .458 hunting round -a type of dum-dum bullet- pulled out of an African buffalo)

Knöchlein denied being at Le Paradis. Then, when residents identified him; he said the executions were justified because the British used dum-dum bullets banned by the Hague Convention.

He also claimed the British had lured his men to the farmhouse with a white flag before gunning them down. Finally, he accused his jailers of subjecting him to physical and mental torture.

The court did not believe any of it, and Knöchlein was hanged on January 28, 1949, for his role in the massacre – the only one punished.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions