Capital punishment was abolished in the second half of the 20th century in the United Kingdom. Death penalty for high treason was taken off the books in 1998, but no one had been executed for that crime since 1946, when William Joyce, nicknamed “Lord Haw Haw,” was hanged for the capital crime of high treason. He was found guilty of broadcasting Nazi German propaganda to the United Kingdom during the World War II.

As for capital punishment for murder, it was abolished in 1965, with the last person who was executed for murder being a young Scotsman named Henry John Burnett, aged 21. He was hanged after being found guilty of the brutal murder of his girlfriend’s husband, a merchant seaman named Thomas Guyan.

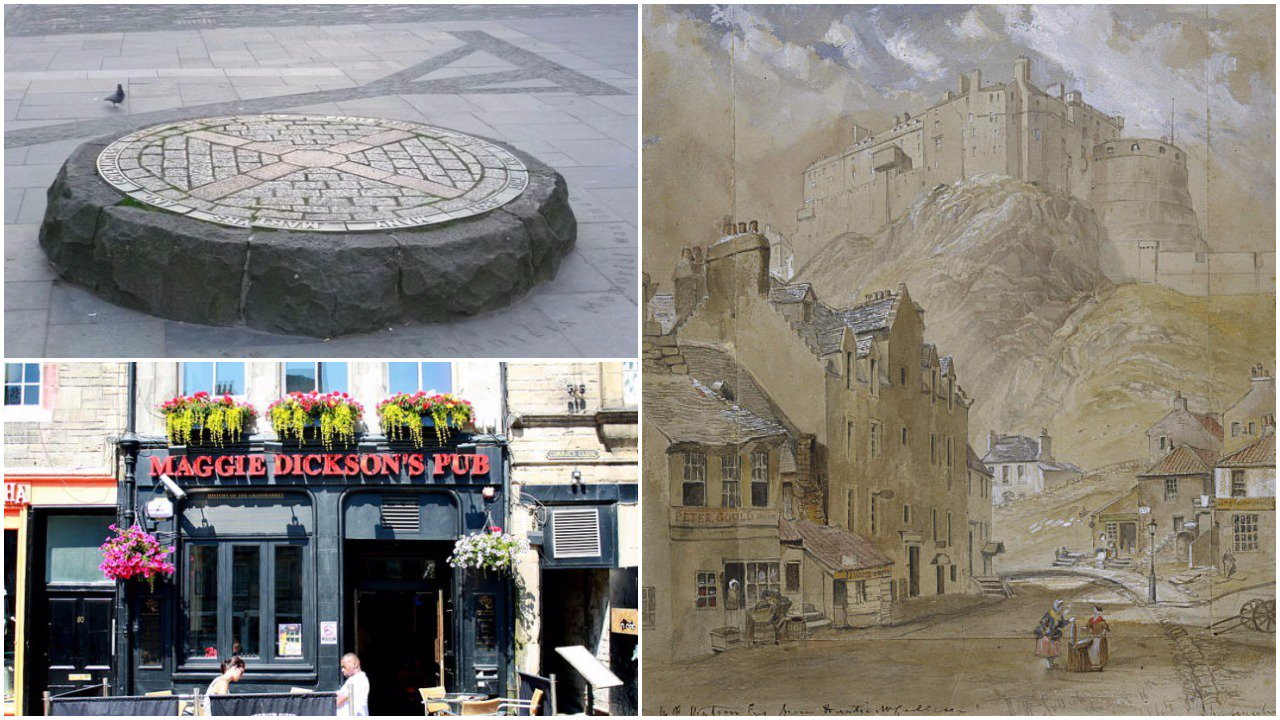

(Grassmarket in Edinburgh: shadow of the gibbet delineated in paving on the site of public executions, next to the Covenanters Memorial from 1937)

From the beginning of the 19th century until the abolishment of capital punishment, those sentenced to death in the United Kingdom were executed in prisons, surrounded by a small crowd that consisted of prison officials, lawyers, and, sometimes, family members. However, earlier in history, executions were public events and regularly attended by large crowds. Some people decided to watch executions out of morbid curiosity, while some came to quench their thirst for grim entertainment.

In Scotland, most public executions took place at the historic market place named Grassmarket in the Old Town of Edinburgh. Nowadays, Grassmarket is a picturesque favorite among both tourists and citizens alike. It is surrounded by historic tenements and overshadowed by the towering Edinburgh Castle; only a small memorial at the center of the market commemorates its bloody history of public executions.

From 1661 to 1688, during the period known as “the Killing Time,” more than 100 people died on the gallows at the center of the Grassmarket. The Killing Time occurred during the reigns of Charles II and James II and the Presbyterian Covenanter movement. Those executed at the Grassmarket were mostly Covenanters condemned to death by the Privy Council.

(Grassmarket, with Edinburgh Castle towering above it)

The most popular tale connected with the Grassmarket’s history of hanging is the one surrounding the execution of Margaret Dickson in 1724. Margaret Dickson was a wife of a poor fisherman who was sentenced to death for the heinous crime of executing her infant child. According to the legend, after she was hanged, she awoke while being transported to the graveyard where she was supposed to be buried.

This allegedly presented a considerable conundrum to the government of the time, since the criminal law stated that those sentenced to death were to be “hanged” and not “hanged until dead.” (The “until dead” part was added in the 1790’s, 70 years after the alleged incident.) Margaret Dickson was reportedly released from custody after her “resurrection” since she had been legally punished for her crime.

(Western end of Grassmarket, painted in 1845)

The botched hanging of Margaret Dickson was not the only incident that exploited the loophole in the death penalty by hanging. In 1775, when the alleged resurrection of Margaret Dickson already became a part of judicial lore, a young advocate named James Boswell intended to use the loophole to save the life of his first criminal client, John Reid.

John Reid was a peasant from Peeblesshire who was sentenced to death by hanging for the crime of sheep-stealing. Boswell was convinced that his client was innocent and intended to hire several surgeons who would resuscitate Reid’s corpse after the execution.

(Maggie Dickson’s Pub, Grassmarket, Edinburgh)

Although Boswell firmly believed in the story of Margaret Dickson’s miraculous recovery, he abandoned his plan for spiritual reasons. Namely, a friend of his persuaded him that, by reviving the condemned peasant, he would cause his soul to burn in hell once he was to die later in life. Furthermore, several days prior to his execution, John Reid stated that he accepted his fate and was willing to die in accordance with the will of God.

Also, those unfortunate enough to die from hanging usually expire from a broken neck and severe internal injuries coupled with asphyxiation. Surgeons of the late 18th century would hardly be capable of a resuscitation that would revive the poor peasant and, even if he had been miraculously revived, he would mostly likely have sustained severe neurological damage from which he would never recover.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions