In several of our articles, we have referred to the issue of national claims after World War II. Today, we will examine the stance of Greek left-wing parties on this matter.

As we will analyze in detail, despite the KKE’s dominance in the sphere of the Left, the positions of left-wing parties were not consistent. Nikos Zachariadis, the General Secretary of the KKE, imprisoned in Dachau, gave an interview in Paris upon his return to Greece, in which he essentially renounced many national claims.

However, upon returning to Greece, he claimed that his statements had been misinterpreted. Additional shifts in Zachariadis’s positions followed, which we will explore below.

Nikos Zachariadis

The KKE’s initial positions and Nikos Zachariadis’s opposing view

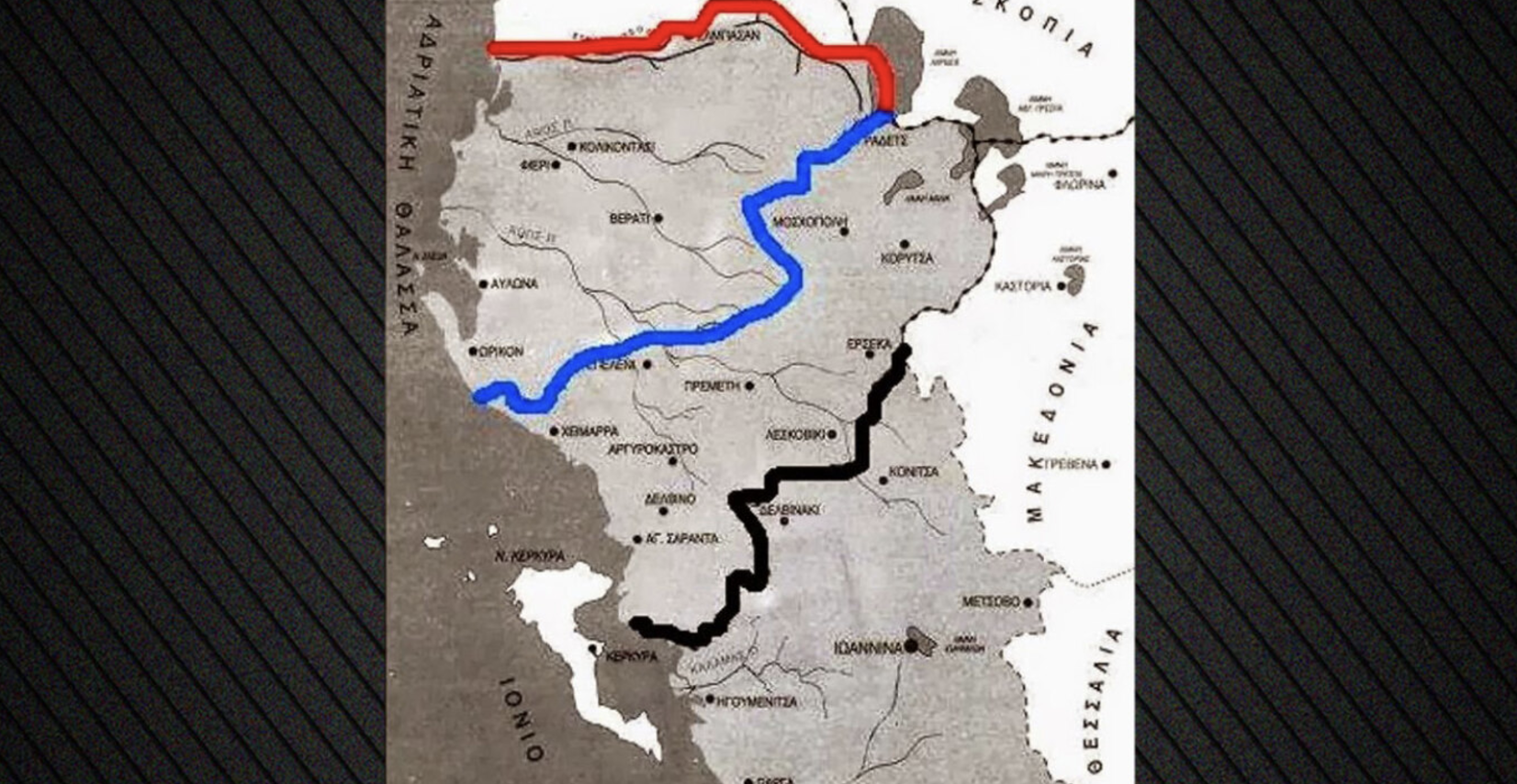

From 1944 to the Paris Peace Conference in 1946, the Left remained largely unified under the EAM. Within this sphere, the KKE’s dominance was undeniable. In May 1944, during the Lebanon Conference, the EAM and KKE agreed to fully support Greek national claims (“Liberator,” May 30, 1944). Other left-wing parties (Socialist Party of Greece, People’s Democratic Union, Democratic Radical Party, Democratic Group, etc.) unequivocally demanded the return of Northern Epirus to Greece.

The “Democratic Group” spoke of new “political borders” resulting from adjustments to Greek-Bulgarian and Greek-Yugoslav borders, which would include Northern Epirus. Additionally, it advocated for a revision of the Treaty of Lausanne in favor of Greece. Regarding Cyprus and the Dodecanese, it vaguely mentioned that the islands in the Eastern Mediterranean were always Greek but acknowledged that the Allies had interests there, suggesting that Greece should be prepared to safeguard these.

The issue of Greek-Bulgarian border changes

The KKE’s leadership did not have a unified stance on national claims. Their positions ranged from conditional acceptance of all claims to supporting only specific ones. Nikos Zachariadis, the KKE General Secretary, imprisoned in Dachau (1941–1945), gave an interview to Greek journalists in Paris on May 25, 1945, on his way back to Greece. The Greek newspaper Empros presented Zachariadis’s interview as exclusive, though this was not particularly significant. Zachariadis’s statements, published on May 26, 1945, in Greek newspapers, essentially portrayed him as opposing national claims.

Empros, September 7, 1946

According to reports in the Greek press, Zachariadis proposed referendums for the fate of the Dodecanese and Cyprus. He considered raising claims for Northern Epirus and Eastern Rumelia a threat to peace and Balkan cooperation. Civil political parties and their affiliated newspapers seized the opportunity. To Vima commented on Zachariadis’s statements as follows: “The entire political world condemns Mr. Zachariadis’s statements on our national claims” (To Vima, May 27, 1945).

Empros, September 19, 1946

Alarmed by the backlash, Zachariadis, upon his arrival in Athens on June 1, 1945, quickly claimed that the interpretation of his statements was due to a misunderstanding. In a press conference, he argued that he did not dispute the desires of the Greek people but rather the method of pursuing them. For Northern Epirus, he proposed a referendum—not because he doubted Greek rights to the area, but because he wanted the matter resolved democratically and not through a coup. Ultimately, Zachariadis declared that the KKE would abide by the decisions of the Greek people, even if those involved military action to claim the region.

Regarding the Greek-Bulgarian borders, Zachariadis acknowledged the issue of their security but considered it primarily a political matter. He believed that two democratic countries could resolve it within 24 hours. Among the issues raised at the time was the return of Eastern Thrace to Greece. Zachariadis emphasized that he would comply with the Greek people’s decisions. It appears that the issue of Eastern Thrace arose due to Soviet pressure on Turkey and was subsequently raised by the Greek side.

In Zachariadis’s interview, there is no mention of the Dodecanese or Eastern Rumelia. On the contrary, he referenced Cyprus and expressed surprise that no official claim had been made by the Greek governments for an island with a clear Greek identity. These positions were later adopted by the KKE’s Political Bureau (Rizospastis, June 2, 1945).

The Positions of the KKE up to the Paris Peace Conference (1946)

In general, the positions of the KKE were often vague and controversial. Zachariadis sought collaboration among all “democratic parties” with the goal of drafting a program for the national restoration of the country, which would also include defense against “reactionary parties” attempting to manipulate the national sentiments of the people to sow division. A decision from the 11th Plenum of the Central Committee of the KKE (April 5–10, 1945) referred to supporting national claims without listing them explicitly.

Front Page for the Paris Peace Conference, 1946

During the 12th Plenum of the Central Committee of the KKE, held from June 25 to 27, 1945, and attended by the party’s General Secretary N. Zachariadis, efforts were made to “reassure its critics that it fully embraced national demands.” The KKE advocated for referendums in Cyprus, the Dodecanese, and Northern Epirus. In fact, regarding Northern Epirus, it adopted the stance of its military occupation with the approval of the majority of the Greek people! This position caused an uproar among “sister” international parties. For this reason, Mitsos Partsalidis criticized Zachariadis—though this only occurred in March 1950! In a 2001 article, Michalis Lymberatos argued that Zachariadis’ positions were “completely inconsistent” with Soviet policy.

In early June 1945, the Central Committee of the EAM convened. Among the participants were: N. Zachariadis, G. Siantos, and D. Partsalidis (KKE); K. Gavriilidis and D. Thanasekos (Agrarian Party of Greece); M. Kyrkos and A. Loulis (Democratic Radical Party); G. Georgalas and D. Marangos (Unified Socialist Party of Greece); and S. Kritikós and E. Proimakis (Democratic Union). The EAM proposed a joint meeting of all parties to unanimously determine the national claims. The text included full acceptance of these demands, including the arrangement of the Greek-Bulgarian borders.

Mitsos Partsalidis

In reality, the KKE was primarily focused on its own claims. The “nationally-minded” factions believed that if the KKE were excluded from the “national core,” they could resolve the country’s acute social issues and expand its borders.

The KKE reacted by demanding participation in shaping foreign policy in order to prevent “new national betrayals by those shouting ultra-patriotic slogans.” It protested its exclusion from the Foreign Affairs Committee, which fractured the country’s unified “appearance” abroad.

Tsoúderos before the Foreign Affairs Committee

On July 6, 1945, Tsoúderos proposed, at the conclusion of the discussions, that a subcommittee invite the KKE and inform it regarding the national claims. Tsoúderos considered the collaboration of the KKE important for Greece’s international standing. If the KKE agreed, Greece would benefit; if it disagreed, it would harm only itself! The newspaper Anatoli in Cairo published a telegram from Athens, according to which, on July 14, 1945, Nikos Zachariadis signed an agreement with the Bulgarian Communist Party and Tito, stating his opposition to Greek claims in the north. However, the Ministry of the Interior informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on July 31, 1945, that it had no evidence to confirm the above claims.

From the summer of 1945 until the spring of 1946, the KKE’s positions on national claims remained steadfast. In fact, a delegation from the party that visited Moscow in January 1946 declared in the Moscow newspaper Trud that the EAM’s demands for the union of Cyprus, Eastern Thrace, the Dodecanese, and Northern Epirus with Greece, as well as the adjustment of the Greek-Bulgarian border, were non-negotiable.

Headline referencing the arrival of Nikos Zachariadis in Athens

The vacillations of Zachariadis and the KKE in 1946

From the spring of 1946, the stance of the KKE began to shift. On May 13, 1946, Zachariadis, in a speech before party members, accused the government of trying to revive the “Great Idea” because it had nothing else to offer the people. However, just three days later, on May 16, the Rizospastis called for the pursuit of claims, including Cyprus and Eastern Thrace—completely contrary to what Zachariadis had said. If anyone was invoking the “Great Idea,” it was the KKE itself, not the government!

During the Peace Conference, Zachariadis hardened his stance even further. On September 8, 1946, he accused the government of being a pawn of the Anglo-Americans in the Balkans. Referring to border incidents at the Greek-Albanian frontier, he described them as the result of “irrational and reckless claims by the monarcho-fascists under Anglo-American instructions” (Stephen G. Xydis, “Greece and the Great Powers 1944-1947,” Thessaloniki: E.M.S.-I.M.C.H.A., 1963). On October 10 of the same year, Rizospastis blamed the failure at the Conference on the policies of the Greek governments since 1944, in both foreign and domestic matters.

When Greece’s hopes were officially dashed with the decisions of the Council of Foreign Ministers in New York, Rizospastis accused Tsaldaris’s People’s Party of chauvinism, neo-fascism, and incompetence in handling national claims, particularly emphasizing the failure to advance issues related to Cyprus and Eastern Thrace. It also directly accused Tsaldaris and Filippos Dragoumis, a member of the Greek delegation in Paris, of abandoning the country’s political demands under Anglo-American guidance.

The constant references to Eastern Thrace and Cyprus by the KKE

The KKE’s repeated mention of Eastern Thrace and Cyprus caused discomfort for the Greek government. Regarding Cyprus, all other parties agreed that the issue should be raised but disagreed on the timing and method. After World War II, Greece relied heavily on British economic aid and support, naively counting on them to assist with other national issues. This procrastination and indecision on the Cyprus issue eventually led to the London–Zurich Agreements and, in the long term, to today’s unacceptable status quo.

As for Eastern Thrace, which, let us recall, was handed over to the Turks without a single shot being fired through the Armistice of Mudanya, the government of the time believed that the KKE’s references aimed at creating impressions and obstacles to the Anglo-American-driven efforts to improve Greek-Turkish relations. Unofficially, some within the government raised the issue of Eastern Thrace, but officially, according to Foreign Office archives, the then-Regent, Damaskinos, stated that Eastern Thrace was not an issue for Greece (F.O.: 371/48344, R 15384/210/19, September 8, 1945).

The Left and its presence at the Paris Peace Conference

Ultimately, the Left found a way to present its positions in Paris. This was done through a letter from EAM to the Great Powers, signed by Partsalidis for the KKE, Gavriilidis for the Agrarian Party, Georgalas for the Socialist Party, Loulis for the Democratic Radical Party, Kritikou for the Democratic Union, and Grigoriadis for the Party of Left Liberals. Dated July 30, 1946, the letter was addressed to the Presidency of the Peace Conference to be conveyed to the delegations of the Great Powers (Foreign Ministry Archives, 172.4/1946 (handwritten), September 6, 1946, 1404/Η, Dragoumis (Paris), to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

The letter begins by stating that the EAM-affiliated parties believe they represent the majority of the Greek people and therefore convey its “voice.” It then focuses on the issues of national security and independence, the restoration of democracy, and political rights, alongside the withdrawal of all foreign troops from the country. It calls for the return of the Dodecanese to Greece and also demands Cyprus, whose overwhelmingly Greek population wishes for union with Greece.

While Cyprus is under British control, the letter argues this should not be an obstacle but a moral obligation. It also demands the return of Northern Epirus and Eastern Thrace, regions that were predominantly Greek before their populations were altered—especially in Eastern Thrace. Additionally, the letter addresses the need to secure the borders with Bulgaria and for Greece to receive fair reparations, given its significant sacrifices for the common cause during the war.

What explains the KKE’s vacillations?

The KKE did not want to be forced into a clear position on national claims. On social and economic issues, it had solid, theoretically and practically supported views. However, on national matters, it appealed to the Greek people, whose national sentiment is deeply ingrained. How could the Left reconcile its theory of a world without borders, based on the class consciousness of workers, with entrenched perceptions of nationhood? And how, from a political standpoint, could it support national claims without clashing with the fraternal parties of neighboring countries, which held power and whose support it also sought?

Thus, the KKE’s stance on national claims could never be unequivocal, leading to its many inconsistencies. Other parties succeeded in trapping the KKE in this slippery field, weakening it in the process. In its attempt to avoid appearing “inferior” to the “patriotic” parties, the KKE sometimes adopted extreme nationalist positions, such as demanding the return of Eastern Thrace.

This shift was even noted by other leftist parties, like the Communist Internationalist Party of Greece and the Archiomarxist Party, which criticized the KKE. Zachariadis struggled to address these criticisms while also countering accusations that the KKE was an “anti-national party.” He believed such accusations were attempts to exclude the KKE from political life and undermine potential collaborations it sought, such as with the Democratic Center.

What did Zachariadis say about national claims after 1949?

After the end of the Civil War, and with the KKE being illegal and “exiled,” it could no longer pursue the same political objectives, at least not immediately. Zachariadis condemned his own (!) policy on national claims as “a product of nationalist blindness.” However, in 1956, he once again linked the policy around national issues “with the convergence of the broader democratic world based on the patriotic orientations of the party.”

Peter J. Stavrakis, in his book Moscow and Greek Communism 1944-1949, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1989, mentions another factor that explains the KKE’s stance. Party members from Epirus pressured the leadership to insist on the incorporation of Northern Epirus into Greece. Thus, the party found itself in the difficult position of supporting views it essentially disagreed with. In 1966, Zachariadis stated, “If the policy of neutrality and peaceful coexistence (‘two poles’) had been adopted in essence by the international communist camp itself, Greece would have had excellent opportunities towards both Cyprus and Egypt and Syria.” He continued, “The party, despite doubts, accepted all the national objectives that reason, the well-understood notion of patriotism, and the international needs of the country dictated.”

According to Zachariadis, in order to “ensure the cohesion of the EAM alliance, the KKE engaged in a desperate attempt to reassure its social allies within EAM.” All positions on national issues, he explained, “were due to efforts to reassure the social allies of the KKE within EAM.” Finally, according to an unsigned editorial in Rizospastis on June 13, 1945: “The General Secretary of the KKE believed that with the support of the USSR, the Italian reparations could be achieved, and that the KKE could play a mediating role between Greece and the Soviet Union, so that the latter could support Greece’s national interests against those who opposed them—this would mean a change in the Soviet Union’s stance.”

It seems that the KKE itself was unsure of what Greece should ask for in Paris in 1946 or suggested completely unrealistic demands.

Unfortunately, the same issue existed within the governing bodies as well. As a result, we reached the point where Bulgaria, one of the Axis states, retained Southern Dobruja, which had been granted to it by the Treaty of Craiova in 1940; Albania appeared as a state that had fought against the Axis powers and remained unscathed; and Greece, which suffered greatly during WWII, with huge losses in both manpower and infrastructure, was content with the cession of the Dodecanese.

Source: Periklis H. Christides, DIPLOMACY OF THE IMPOSSIBLE, UNIVERSITY STUDIO PRESS, 2009.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions