An FBI translator with a top-secret security clearance traveled to Syria in 2014 and married a key ISIS operative she had been assigned to investigate, CNN has learned.

The rogue employee, Daniela Greene, lied to the FBI about where she was going and warned her new husband he was under investigation, according to federal court records.

Greene’s saga, which has never been publicized, exposes an embarrassing breach of national security at the FBI—an agency that has made its mission rooting out ISIS sympathizers across the country.

It also raises questions about whether Greene received favorable treatment from Justice Department prosecutors who charged her with a relatively minor offense, then asked a judge to give her a reduced sentence in exchange for her cooperation, the details of which remain shrouded in court-ordered secrecy.

The man Greene married was no ordinary terrorist.

He was Denis Cuspert, a German rapper turned ISIS pitchman, whose growing influence as an online recruiter for violent jihadists had put him on the radar of counter-terrorism authorities on two continents.

In Germany, Cuspert went by the rap name Deso Dogg. In Syria, he was known as Abu Talha al-Almani. He praised Osama bin Laden in a song, threatened former President Barack Obama with a throat-cutting gesture and appeared in propaganda videos, including one in which he was holding a freshly severed human head.

Within weeks of marrying Cuspert, Greene, 38, seemed to realize she had made a terrible mistake. She fled back to the US, where she was immediately arrested and agreed to cooperate with authorities. She pleaded guilty to making false statements involving international terrorism and was sentenced to two years in federal prison. She was released last summer.

A Justice Department official, however, said Greene’s sentence was “in line” with similar cases, but declined to cite examples.

After Greene finished cooperating with authorities, prosecutors asked the judge to unseal portions of the court file, including Greene’s identity.

“Unsealing these documents will allow appropriate public access to and knowledge of the circumstances of this case,” prosecutors stated.

Greene, who now works as a hostess in a hotel lounge, said in a brief interview with CNN that she was fearful of discussing the details of her case.

“If I talk to you my family will be in danger,” Greene said. She declined further comment.

CNN is withholding Greene’s location in the US and has obscured her face in photos and videos due to concerns raised about her safety.

Her attorney, former assistant federal public defender Shawn Moore, said he could not comment on details of the case, citing attorney-client privilege constraints and national security restrictions.

He described Greene as “smart, articulate and obviously naïve.” He said she was “genuinely remorseful” for her actions.

“She was just a well-meaning person that got up in something way over her head,” Moore said. He declined further comment.

“She was a really hard worker…”

There is nothing readily apparent in Greene’s past to suggest she would one day find herself the bride of an international terrorist.

Born in Czechoslovakia and raised for a time in Germany, she married a US soldier at a young age and moved to the United States, several friends and acquaintances recalled. She went by the nickname Dani.

She attended college at Cameron University in Oklahoma where she was on the dean’s list. She then went to graduate school at Clemson University where she earned a Master’s Degree in history.

“I could see she was a really hard worker,” said Clemson Professor Alan Grubb, who advised Greene on her thesis, which explored “racial motivations for French collaboration during the Second World War.”

“She was one of our better graduate students, I thought,” he said.

Grubb recalled writing a letter of recommendation for her for a job that involved translating for a federal government agency.

Fluent in German, Greene went to work for the FBI as a contract linguist in 2011. It was a job that, following a grueling application and vetting process, came with a top-secret national security clearance.

Greene was assigned to the bureau’s Detroit office in January 2014 when she was put to work “in an investigative capacity” on the case of a German terrorist referred to in court records only as “Individual A.”

CNN identified “Individual A” as Cuspert using court documents, newspaper articles about his music career and transformation to jihadist, government bulletins, videos and other sources. His identity was ultimately confirmed by a source familiar with the investigation.

From Gangsta Rapper to Jihadist

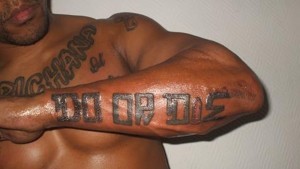

Before Cuspert became a front man for jihadists, he was known as Deso Dogg in Germany. Tattoos on each hand spell out the image he cultivated in the mold of American gangsta rappers.

“STR8” was inked on one hand, “THUG” on the other.

One CD cover featured Cuspert with a menacing glare, holding a gun to his own head. His image was backed up by a real life rap sheet with a string of arrests.

He had a lean, muscular physique and trained in various martial arts.

Cuspert never achieved star status in the music world, but he did enjoy some success: In 2006, he opened for popular US rapper DMX.

A near-death experience in a car accident prompted Cuspert to turn to religion, according to numerous press accounts. In 2010, he quit the rap world and converted to Islam. He traded his hard driving gangsta-style lyrics for Islamic devotional songs called Nasheeds, including one that praised bin Laden.

Cuspert gained some notoriety as an extremist in 2011 after he posted on Facebook a fake video purportedly showing US soldiers raping a Muslim woman. The video motivated a man to carry out a terrorist attack on the Frankfurt airport, killing two US airmen and wounding two others, according to The New York Times.

In 2012, Cuspert fled Germany, reportedly spending time in Egypt and Libya. The following year, he arrived in Syria, where he would emerge as “ISIS’s Celebrity Cheerleader,” according to a report from the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), a group that monitors various topics in the region, including violent extremism.

As part of the FBI’s investigation into “Individual A,” Greene identified several online accounts and phone numbers used by the terrorist, according to the court file.

Among them were two Skype accounts. She maintained “sole access” to a third Skype account, the records state.

It was in April 2014, during Greene’s work on the investigation, that Cuspert appeared in a video declaring his allegiance to ISIS and its leader, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi.

He called ISIS “the state that no one can stop,” adding, “we will continue to build it until it reaches Washington… Obama!” He then made a throat-cutting gesture with his finger, according to the MEMRI report.

On June 11, 2014, Greene filled out a Report of Foreign Travel form — a document FBI employees and contractors with national security clearances are required to complete when traveling abroad.

Greene, who was still married to her American husband at the time, characterized her travel on the form as “Vacation/Personal,” court records show.

“Want to see my family,” she wrote. Specifically, Greene said, she was going to see her parents in Munich, Germany.

She boarded an international flight on June 23, 2014. But her destination wasn’t Germany. She flew instead on a one-way ticket to Istanbul, Turkey, where she had reservations at the Erguvan Hotel. From there she traveled to the city of Gaziantep, about 20 miles from the Syrian border.

She contacted “Individual A,” the documents state, and with the assistance of a third party arranged by him, crossed the border into Syria. Once there, according to the court records, she married him.

Shortly after, Greene sent emails from inside Syria to an unidentified person in the US showing she was having second thoughts and suggesting she knew she was breaking the law.

“I was weak and didn’t know how to handle anything anymore,” she wrote on July 8. “I really made a mess of things this time.”

In another email the following day she wrote: “I am gone and I can’t come back. I wouldn’t even know how to make it through, if I tried to come back. I am in a very harsh environment and I don’t know how long I will last here, but it doesn’t matter, it’s all a little too late…”

On July 22, 2014, she again wrote to the unidentified recipient: “Not sure if they told you that I will probably go to prison for a long time if I come back, but that is life. I wish I could turn back time some days.”

While Greene was expressing regrets, Cuspert was actively fighting ISIS’s battles.

A video from July 2014 “showed glimpses of him in the bloody aftermath of the ISIS takeover of the Al-Sha’er gas fields in Homs,” according to the MEMRI report on Cuspert. In a field covered with dead bodies, Cuspert “is seen for several seconds beating a corpse with a sandal,” the report said.

Back in the US

It is unclear from the court file precisely when or how authorities learned of Greene’s actions, but on Aug. 1, 2014, five weeks after she left for Syria, federal authorities secretly issued a warrant for her arrest.

“At that time,” prosecutors would later write, “the defendant was at large in Syria or Turkey in the company of the leader of a terrorist group.”

After about a month in Syria, Greene somehow was able to leave the war-torn country and returned to the United States. She was arrested on Aug. 8, 2014.

In November that year, with Greene in custody and cooperating with the government, prosecutors argued for the court file to remain sealed: “Publicity regarding the arrest of the defendant or the charges against her would contribute to a substantial likelihood of imminent danger to a party, witness or other person as well as a substantial likelihood that the ongoing investigation will be seriously jeopardized.”

What ensued was a succession of secret hearings and court filings.

Then, on April 17, 2015, prosecutors told the judge Greene’s cooperation had concluded. The following month, portions of the case file were unsealed, though the judge kept some material secret.

Gillice, a prosecutor in the National Security Section of the US Attorney’s office in Washington D.C., wrote that Greene placed herself and her country in serious jeopardy.

“She endangered our national security by exposing herself and her knowledge of sensitive matters to those terrorist organizations,” he wrote. “Her escape from the area unscathed, and with apparently much of that knowledge undisclosed, appears a stroke of luck or a measure of the lack of savvy on the part of the terrorists with whom she interacted.”In his argument for a reduced sentence, Gillice noted that Greene immediately began cooperating with authorities. Her cooperation was “significant, long-running and substantial,” he wrote.

“After the egregious abuse of her position, the defendant attempted to right her wrongs, and to ultimately assist her country again,” the prosecutor wrote.

A Special Designation

A month after Greene secretly pleaded guilty in December 2014, an item appeared in the US government’s federal register about the man that only handful of people knew she had married.

It was a notice from then-Secretary of State John F. Kerry dated Jan. 9, 2015.

“I hereby determine that the individual known as Denis Cuspert, also known as Denis Mamadou Cuspert, also known as Abou Mamadou, also known as Abu Talha the German…committed, or poses a significant risk of committing, acts of terrorism that threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.”

The obscure posting was a precursor to the State Department declaring Cuspert a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” in February 2015 in a bulletin on the agency’s website.

The bulletin cited his oath of loyalty to ISIS and his appearance in a video in which he held a severed human head he said belong to man executed for opposing the group.

It called Cuspert “a willing pitchman for [ISIS] atrocities” and said he appears to be a recruiter with a special emphasis on recruiting German speakers to the terrorist organization.

The bulletin made no mention of him having recently married an employee of the FBI.

But days after the State Department bulletin was posted, a German newspaper published a report saying Cuspert had married an FBI spy.

The report, citing unnamed US and German intelligence officials, did not name the spy.

The report was also at odds with Greene’s case on a fundamental level: It described the operation as an FBI-sanctioned plot in which Cuspert was duped by a spy, not as the work of a rogue employee who broke the law and betrayed her country in the process.

Several news outlets ran brief stories summarizing the German report. The FBI declined comment and the matter died without Greene’s identity or true role being revealed.

In October 2015, the Pentagon said Cuspert was killed in an air strike near the northern Syria city of Raqqah.

Nine months later, on August 3, 2016, the Pentagon released a statement reversing its assessment of Cuspert’s death: “It now appears that assessment was incorrect and Denis Cuspert survived the airstrike.”

One day later, Greene was released from federal prison, records show.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions