Two years ago, on the Friday before Clean Monday, which marks the end of the carnival period and the beginning of Lent for the Greek Orthodox Church, Eleni Baharidou and her husband Stefanos, a soldier, were sitting down to dinner at a local taverna when his phone rang. The voice on the other end ordered him to gather his equipment and immediately report to a military camp at the Kastanies/Pazarkule border crossing.

“There was no warning,” said Baharidou, president of a group of civilian volunteers in Nea Vyssa, a village in northern Evros near Kastanies. “They called him in around 11 p.m., and I didn’t know what happened until we spoke on the phone the next day.”

That same evening, 130 kilometers south in the city of Alexandroupoli, Dimitrios Dimitrakopoulos, owner of the Café de Paris, saw all the fighting-aged men in his cafe suddenly stand up and leave after having received word of an incident at the northern land border with Turkey.

It was February 28, 2020, after 33 Turkish troops had been killed by Russian and Syrian airstrikes in Idlib. In an attempt to pressure Europe for greater support, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made good on his long-time threat to once more inundate the bloc with the thousands of Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Syrian migrants Turkey had agreed to keep from the border. The Turkish government shuttled migrants from Istanbul and other towns to a border checkpoint named Pazarkule. Many more rushed there when they heard Turkey would allow them to cross unimpeded.

In response, the Greek government sealed its borders and controversially suspended asylum applications for a month, a decision that according to the UN Refugee Agency had no legal basis. Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis warned migrants not to cross, tweeting, “I want to be clear: no illegal entries into Greece will be tolerated. We are increasing our border security.”

Caught off-guard by the masses gathering in the buffer zone between Pazarkule and Kastanies, local police and army forces struggled to hold the border until reinforcements arrived. “The first 24 to 48 hours were the most critical because we didn’t have the forces we needed,” said Chrysovalantis Gialamas, president of the Association of Border Guards of Evros. “It was unprecedented and clearly directed by the Turkish side, using all those people as a tool for their own interests.”

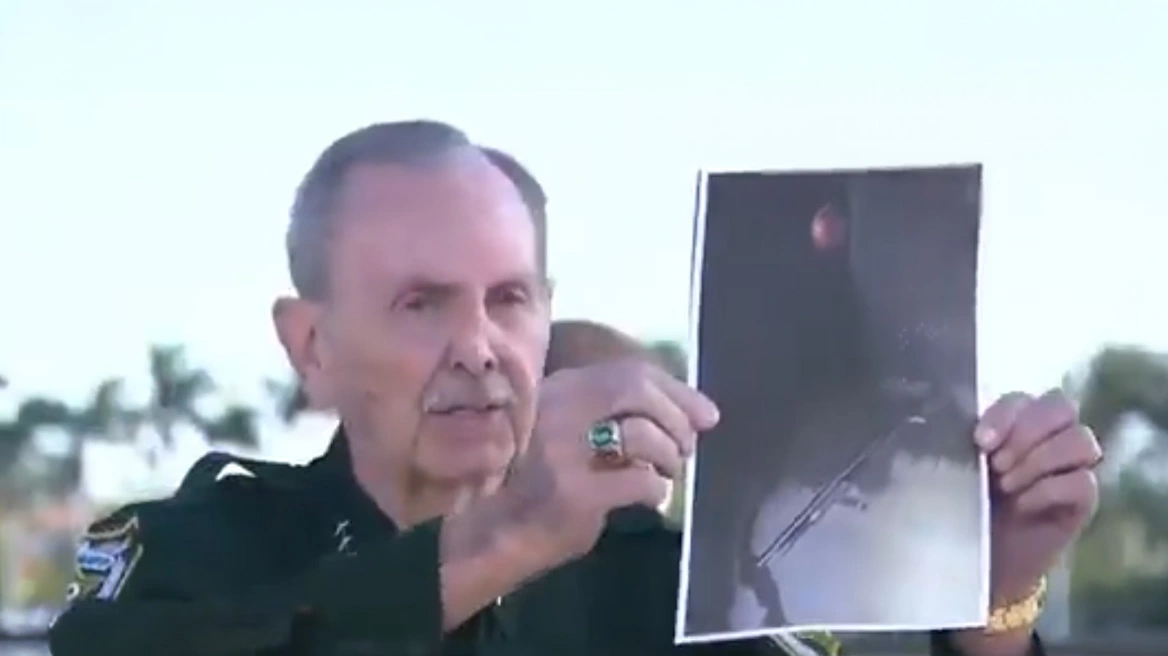

Greek soldiers blocked the checkpoint with a bus and laid thick loops of razor wire to strengthen their defenses. Working throughout the night, they deterred an estimated 4,000 migrants from crossing and arrested 66. By Saturday morning, there were approximately 6,000 to 7,000 people on the Turkish side of the border. Young men packed into the buffer zone and tried to breach the border fence. They set fires and threw rocks, sticks, smoke bombs and Molotov cocktails, shouting to be let in. Turkish forces assisted, attempting to pull down sections of the fence.

Germany to consider paying for gas in Rubles, the Kremlin says

Greek security officers fired tear gas and firefighters doused the crowds with water, while riot police with batons and shields warned them to keep back. “Everything we did to confront the difficulty wasn’t because we’re racists or we don’t accept people who aren’t Greeks in Greece,” Baharidou said. “But a person who comes from a war zone wanting to save his life and his family doesn’t come to break, burn or do such violence. And there were thousands of them, all young men. Where were they planning to go? Realistically, such a thing could not happen.”

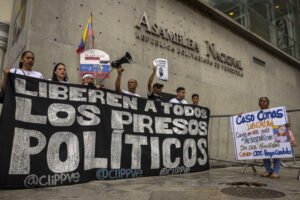

Still, the crisis drew scrutiny from groups concerned about the suspension of the asylum process, violations of human rights and attempts by far-right groups to take advantage of the tensions. Shots from the Greek side reportedly resulted in the deaths of Muhammad al-Arab and Muhammad Gulzar, although the Greek authorities insist that only non-lethal means were used.

“This story with the refugees is a tragic story,” Giannis Laskarakis, a writer and former publisher of the left-leaning, Alexandroupoli-based newspaper H Gnomi, told me. “These were dirt-poor people who wanted to go to Europe, as always. And we brought the army with canons and fired at them. It’s unbelievable what happened.”

The incident, which Gialamas refers to as the “Evros war of 2020,” brought this often-neglected northeastern corner of Greece into the spotlight. When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen visited Evros in March of that year, she affirmed the importance of Greece’s borders as the external borders of Europe and thanked Greece for being Europe’s aspída or “shield.” She also announced 700 million euros in European Union funding for Greece, half of which would be available immediately to upgrade border infrastructure. Frontex, the European border and coast guard agency, deployed an additional 100 guards to the region, while France, Austria, Cyprus and Poland sent additional vehicles and personnel.

Read more: ICWA

Ask me anything

Explore related questions