Turkey’s referendum on presidential powers had just finished. Counting was under way. Then, supervisors at more than 167,000 polling stations received an unprecedented order from election central in Ankara.

They were told to count every ballot, even the ones without an official stamp to verify their authenticity. It was a clear departure from election rules. And it means that the allegations of fraud that have echoed around the country since the April 16 vote, one of the most momentous in Turkey’s history, can probably never be set to rest.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has won every election in the past decade-and-a-half, and he won this one too, but not by much. His proposed changes to the constitution were backed by 51.4 percent of Turks who cast ballots, according to official results. The effects are far-reaching: presidential powers will be expanded, the office of prime minister scrapped, and parliamentary oversight curtailed. A new republic, in other words. Erdogan supporters say it’ll be more stable; critics say it tilts Turkey toward dictatorship.

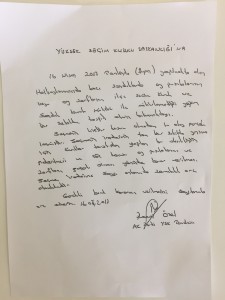

With the margins narrow and the stakes high, it’s not surprising that there’s been intense scrutiny of the ballot process. At the heart of it is a handwritten note from Recep Ozel, the governing Justice and Development Party representative on Turkey’s election board. He asked for — and got — an exception to the election-law requirement that only stamped ballots be counted. Local waivers have been granted in the past, but not a blanket one nationwide.

‘Some Bureaucrat’s Mistake’

The purpose of having those stamps is “to prevent fraudulent ballots, votes brought in from outside,” said Ozel. He knew the decision, requested by his party headquarters, would cause uproar. But, he said in an interview on Tuesday at the board’s office in Ankara, it had to be done. Officials at polling stations had been handing out unstamped ballots, “we can’t even guess how many,” and voters had been using them. Refusing to count them would be undemocratic.

“Yes, there was a big negligence here, but if you’re a voter, was it your fault?” Ozel said. “You can’t sacrifice a citizen’s vote because of some bureaucrat’s mistake.”

As Ozel spoke, lines of people were waiting to file complaints at the election board’s office, showing that his take on the decision isn’t universal. There’s also been international skepticism of the referendum result — notwithstanding U.S. President Donald Trump’s congratulatory phone call to Erdogan.

According to the opposition, it’s not clear that Erdogan actually won.

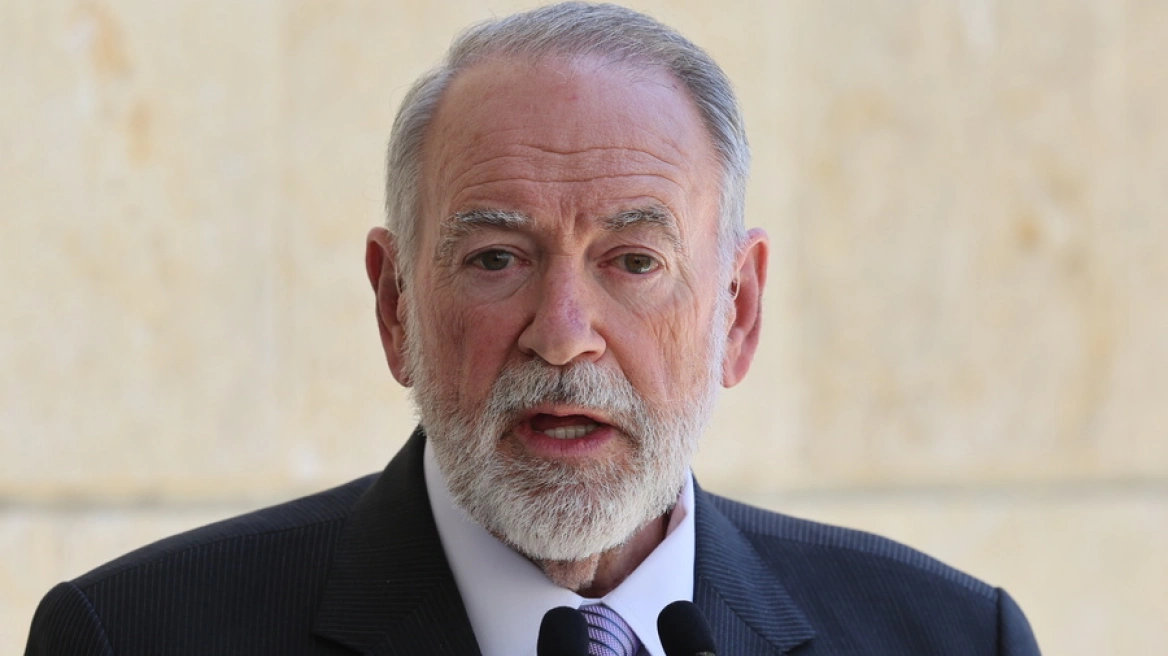

At the Republican People’s Party headquarters in Ankara, Deputy Chairman Erdal Aksunger says he has suspicions over about 5 million votes. The government’s winning margin was 1.2 million.

‘It Means Fraud’

“Starting from the morning hours, we got complaints from almost 10,800 polling stations,” said Aksunger, whose party is the main parliamentary opposition. “This is extraordinary, and when it happens, it means fraud.”

He pulls out documents from a stack. At almost 1,000 polling stations, every single vote was ‘yes,’ Aksunger said. At hundreds of them, there were more votes than registered voters. Government officials say the deployment of additional security forces, who can vote wherever they’re sent, explains some apparent discrepancies.

The election board rejected the Republicans’ call for a re-run of the vote. Erdogan dismissed concerns about voting procedures, including those raised by monitors from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. “The referendum is over, and debates on it are behind us,” the president said on election night.

Turkish votes have often been followed by allegations of malpractice, if not usually on this scale. They often focus on the nation’s Kurdish southeast, where separatist violence and martial-law type conditions make monitoring difficult. It’s also the part of Turkey where Erdogan’s support got the biggest bump.

‘Not By Choice’

The main Kurdish party did make an effort to scrutinize balloting, but says it was hampered by intimidation and arrests, while ballot-box locations were shifted. “We think 300,000 of our voters didn’t go out to vote, and not by choice,” said Ahmet Yildirim, its deputy chairman. On the other hand, Erdogan’s always had a following in the region, while the Kurdish party is accused of links with groups classified as terrorists. Ministers said the referendum results show a swing away from separatism.

Irregularities were reported elsewhere in Turkey too. For example, ballot-papers had one side marked “yes” and the other “no,” and voters were supposed to indicate their choice with an inked stamp that read “preference.” But many polling stations handed out stamps that read “yes” — which they then had to imprint onto the “no” side of the ballot, if they opposed Erdogan’s reforms. It was confusing to say the least.

“We don’t know why, in some places, they insisted on sending a stamp that said ‘yes’,” Ozel said. “We intervened against this, and at about 10 o’clock [a.m.] it was changed.”

For Mehmet Hadimi Yakupoglu, the biggest concern remains the counting of ballots that weren’t stamped by election authorities before they were handed to voters — as a result of Ozel’s intervention.

Yakupoglu is one of Ozel’s opposition counterparts on the election board. The body is made up of 11 full members, all judges, and another four non-voting representatives, one from each of Turkey’s parliamentary parties. The board was caught up in purges that followed last year’s failed coup attempt. Eight of the judges were appointed in September, and had never overseen a vote before Sunday.

‘We’ll Never Know’

Yakupoglu says the unstamped ballots should’ve been thrown out as invalid. Instead, an unknowable number got stamped after the fact, and that “robbed me of my ability to audit the vote.”

Ozel acknowledges as much: “They could’ve been stamped in advance, or they could’ve been stamped later.” He accepts that mistakes were made, but said there was no sinister intent. “I’d bet my name on it that this was a fair election,” he said.

Yakupoglu says such assurances aren’t good enough.

“The election wasn’t secure,” he said from his office abutting Ozel’s. “There’s no way of knowing what happened, even if we recounted all of the votes. This is like toothpaste. Once it’s out of the tube, you can’t put it back. We will never know.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions