After banking on neglect, hostility and mistreatment to discourage a steady trickle of migrants, the new French government was ordered by France’s highest administrative body to do better this week and at least provide water and toilets to the people.

That order has defused, for now, a new migrant crisis brewing at the northern port of Calais, the favored would-be jumping off point for Britain. Yet a permanent solution to France’s slow-boiling migrant problem still appears to be distant.

That has not stopped the French authorities from trying. In recent days, President Emmanuel Macron proposed opening European-run reception centers in Africa — perhaps in Niger, Chad or even Libya — to discourage migrants from risking the journey across the Mediterranean Sea.

Critics quickly pointed out the fierce determination of Africans to make the journey, regardless of counsel to the contrary, and the huge numbers intent on doing so.

Up to one million migrants are in refugee camps in Libya alone, as Mr. Macron pointed out in a speech in which he highlighted his own recent peacemaking initiative for Libya. He also called for broader European involvement in African development as a long-term solution to the migrant crisis.

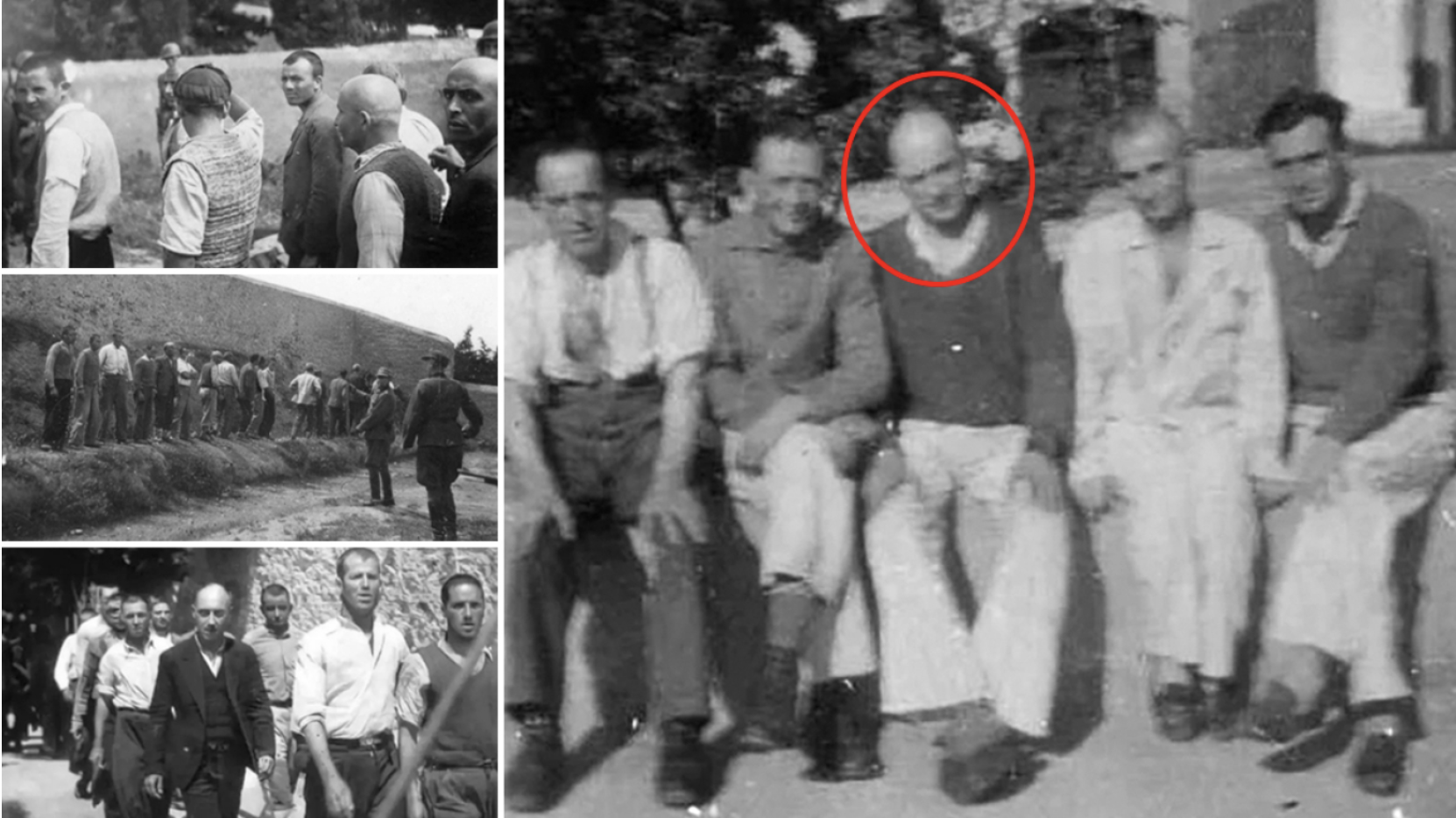

Eight months after the government destroyed a sprawling migrant encampment of about 9,000 migrants at Calais, up to 700 migrants — Eritreans, Ethiopians, Afghans and Pakistanis mostly — are still wandering the area around the Channel Tunnel, sleeping outdoors with no toilets or other facilities.

The migrants have made thousands of attempts to enter the tunnel and board trucks bound for England since the beginning of the year, the police say.

The French migrant numbers are small compared with the thousands pouring into Greece or Italy. In the later, about 95,000 migrants have arrived from across the Mediterranean this year.

But in France, a persistent, and active, humanitarian smuggling network at the Italian border helps fuel the migration, despite a crackdown.

Active mistreatment has not discouraged the migrants reaching France — for example, Human Rights Watch said last week that the police routinely used pepper spray on the migrants. Neither does passive neglect, since the government refused to heed a local court’s order to provide water to the migrants.

But that lower court order was upheld Monday by the Council of State, which criticized Mr. Macron’s government for “inhuman and degrading” treatment of the newest migrants at Calais, in northern France.

On Monday, the council blasted the government’s “manifestly insufficient” accounting for “the elementary hygiene and water needs” of the migrants at Calais by compromising “in a serious and obviously illegal way, a fundamental right.”

Mr. Macron’s interior minister, Gérard Collomb, immediately promised water, showers and toilets for the migrants at Calais, as well as two new regional reception centers where demands for asylum could be processed more quickly. He also promised an investigation into the police’s conduct.

But the mayor of Calais, Natacha Bouchart, pointed out the dangers of the government’s response, saying it would seed a potential rebirth of the sprawling encampment, known as the jungle, that was destroyed last fall. She vowed to resist the order by the council, an agency that conducts studies regarding public policy issues for the government and on its own, according to its website.

“I can’t accept the putting in place of facilities which will once again facilitate the creation of encampments and slums,” she said in a statement late on Monday.

The majority of residents of Calais might agree. The leader of the right-wing National Front, Marine Le Pen, won a majority of the vote against Mr. Macron in the second round of the presidential election in May.

Mr. Macron wants a fresh start on policy regarding migrants, but until last week he had mainly allowed his tough-talking interior minister to set the tone: no coddling of migrants at Calais and harsh words for the humanitarian organizations working there.

The government wanted to avoid setting up new reception centers at Calais or do anything that would encourage migrants to head to that English Channel port, further exasperating local officials.

It has also pledged to step up the expulsion of economic migrants looking for work, as opposed to those seeking political asylum. Less than a third of the 91,000 illegal migrants arrested in France last year actually left the country.

Mr. Macron turned his attention to migrants last week in a speech in Orléans, vowing then to end the phenomenon of migrant encampments in France. “The first fight is to house everybody decently. Between now and the end of the year, I want no more men and women in the streets, in the woods, or lost,” he said.

“It’s a question of dignity, it’s a question of humanity, and of efficiency also,” he said at the end of a ceremony to swear in new French citizens.

“Most of those who are, dreadfully, called migrants today, are not all men and women demanding asylum, coming from countries where their lives are in danger,” Mr. Macron said. “There are many, more and more, who come from peaceful countries, and are following the economic migration routes, who are financing the smugglers, the bandits, even terrorists, and in those cases we need to be strict, tough even, rigorous, with those coming by those routes. We can’t welcome everybody.”

He promoted his own “much more ambitious” European development policy, called the Sahel Alliance, intended to keep the migrants in Africa.

While Africans have welcomed these outlines of initiatives, many reacted angrily to remarks Mr. Macron made at the Group of 20 summit meeting about Africa’s “civilizational challenge.”

“When you have countries where there are still seven to eight children per woman, you can decide to spend million of euros, nothing will be stabilized,” he said.

Despite the angry African reaction, Mr. Macron’s remarks are consistent with the demographic reality in several West African countries that are sources of European migration.

The new president turned aside from the migrant issue in his first months. Instead, he has been preoccupied with reforming France’s economy and meeting foreign leaders, a suddenly plunging popularity rating and a raft of inexperienced parliamentary deputies in his own political movement.

But politically hazardous images of African migrants camping out — in the streets of Paris, at Calais or near the Italian border around Nice — keep turning up in the French news media.

Last month the police in Paris carried out their 34th evacuation of migrants since 2015, removing nearly 3,000 from the Porte de la Chapelle, then busing them to gymnasiums in the region for processing.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions