On the surface, the First Crusade looks like something with a simple cause – the hatred of one religious group for another. In reality, the causes were far more complex. A wide range of factors led to Pope Urban II’s call to arms in 1095, and to the eagerness of men to follow his lead.

A Violent Society

(Madrid Skylitzes illuminated manuscript depicting Byzantine Greeks punishing ninth-century Cretan Saracens)

By modern standards, medieval Europe was a terrifyingly violent place. Physical force was used to achieve all sorts of ends. Lords used violence to exert their influence over their subjects and to pursue feuds with each other for political and financial gain. Issues of international politics were frequently resolved on the battlefield. When they occurred, wars affected everyone in a region through pillage and slaughter. Banditry was rife.

In such a context, men were already primed for violence. Its use was excusable in any cause they deemed right.

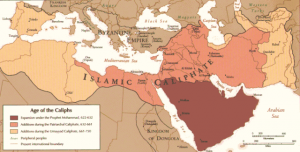

A Struggle the Size of the Mediterranean

(Umayyad Caliphate at its greatest extent)

Though few people were in a position to see it, a struggle was taking place for religious domination in the lands surrounding the Mediterranean. From its birth in the 7th century, Islam had spread out of the Middle East, with Muslim rulers taking over North Africa and large chunks of southern Europe. In the 11th century, Christianity had made a comeback, as Christian lords took over Muslim lands in Spain and Italy.

One of the few institutions with the knowledge, intelligence network and broad geographical and historical perspective to see this was the Papacy. They could see the broader trends and act to drive them in the direction they preferred – one that served both the moral values and the self-interest of the men running the church.

Prejudices

Most Europeans had so little contact with Muslims that they did not even have a warped perspective of who they were, never mind an accurate one. In as far as Europeans were aware of Islam, they understood it as a strange and disturbing thing, a religion of polytheistic idolators. Stories of Muslim atrocities were easily believed, as were strange accounts of the Prophet Muhammad’s life. This made it easy to turn Muslims into scapegoats and targets.

A Cause for Political Cooperation

(Medieval French manuscript illustration of the three classes of medieval society: those who prayed—the clergy, those who fought—the knights, and those who worked—the peasantry)

Rulers of European nations had a fragile grasp on their territories. They could only control them through cooperation with the elites of their nations. These men were as prone to fight authority as to obey it. When an opportunity to create a shared purpose and greater cooperation came up, it was to the advantage of rulers to take it. By supporting the shared cause of crusade, rulers could foster these bonds of cooperation with their followers.

An Elite Warrior Culture

Medieval society was divided into three classes – those who fought, those who prayed and those who worked. For those at the top, their identity as warriors was crucially important. Their sense of identity and their position in society were tied into martial prowess, and into a shared culture of physical toughness and military honor. The only way they could maintain this status, both as individuals and as a group, was to keep fighting.

The crusade gave them an opportunity to do this without disobeying their superiors, incurring the wrath of the church, or putting their own lands at risk. It was a perfect opportunity to live the way of life that they had been told was theirs.

Gregorian Reform

The culture of those who prayed was also important. The church had just gone through a period of transformation known as the Gregorian Reform after one of its leaders, Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085).

These reforms gave the church renewed spiritual vigor and an emphasis on purity that discouraged tolerance of irreligious behavior, whether that was clerics breaking the rules – a common target of the reformers – or heathens living at the edge of Christendom.

As well as helping to motivate the crusade, these reforms gave Pope Urban II a more effective church administration with which to mobilize his crusade.

Deeds to Redeem Sinners

The Gregorian Reform, like the struggle for the Mediterranean, was a broad trend that many outside the church would not have been aware of. But one religious concept was familiar to all Christian Europeans, and that was sin.

In the eyes of medieval Catholics, spiritual salvation was a balancing act. Sinful acts doomed a soul to hell, but righteous acts could balance this, effectively buying off the punishment. One of the most common righteous acts in this economy of damnation was the pilgrimage – traveling to a faraway sight of religious significance.

The crusaders were men who believed by default in sin, damnation, and salvation. Many of them knew they had done wrong, and all were keen to go to Heaven instead of Hell. By making the crusade into an armed pilgrimage, with sins forgiven for those who participated, Pope Urban ensured vast enthusiasm for the undertaking.

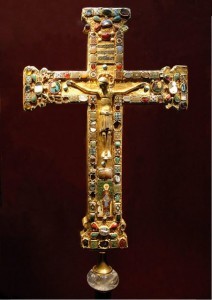

The Importance of Place in Religion

(The Cross of Mathilde, a crux gemmata made for Mathilde, Abbess of Essen, 973-1011, who is shown kneeling before the Virgin and Child in the enamel plaque)

Christian religion was closely tied to a sense of physical place. Rome was the capital of the church. Pilgrimage destinations were sites of salvation. Churches and cathedrals were places of holiness and safety, offering legal as well as spiritual sanctuary. Medieval warriors had been taught that holy places mattered, and nowhere was more holy than the city of Jerusalem. This created enthusiasm for crusading to save that city – a level of enthusiasm not stirred for previous wars.

Primogeniture

Europe was run on primogeniture, the rule whereby the eldest son inherited all his father’s lands, titles, and power. This created stability and helped to forge the great power blocks of the continent. But it also created a problem – thousands of younger sons of aristocrats without inheritance or purpose, trained only to fight.

These men provided much of the fighting force for the crusade, which in return gave them the opportunity to conquer lands for themselves. This created a safety valve, venting these dangerous individuals into another part of the world, away from lives of banditry and civil war.

Biblography: Marcus Bull, (1994), ‘Origins’, in Jonathan Riley-Smith (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades.