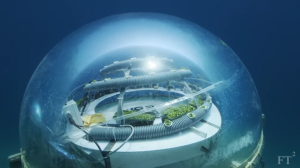

Under eight metres of water close to Italy’s Ligurian coast, what look like giant jellyfish are tethered to the seabed.

Sergio Gamberini, the entrepreneur who designed these striking biospheres, thinks they may offer one answer to feeding the world’s growing population.

While many conventional farmers are innovating in a bid to become more productive, fertile land is at a premium and remains hostage to the elements and to pests. Traditional agriculture can also be environmentally and socially costly owing to its use of pesticides, nutrient runoff and excessive water use.

Five years ago Gamberini, the president of scuba and snorkelling equipment manufacturer Ocean Reef Group, found himself asking if the altogether more radical approach of using the ocean to grow vegetables might work.

With his son Luca he set about experimenting with simplified hydroponics, systems that feed nutrients directly to plants in solution rather than through the soil, to feed plants in shallow sub-surface ‘biospheres’. The system they came up with does not need the power, temperature regulation systems or LED lighting involved in greenhouse farming on land. “I thought I could combine my passions and start to solve this problem,” says Gamberini.

The Italian venture has been growing plants in these transparent biospheres for three years now and they form the heart of the experiment that Gamberini has dubbed Nemo’s Garden, a nod to the hero in Jules Verne’s sci-fi story Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

He admits the idea seems crazy but says there are many advantages to sub-aqua agriculture. The warmth and humidity in his biospheres under the waves is ideal, like that of a conventional terrestrial greenhouse, yet it takes no energy to sustain.

The plants they grow get all they need from the light filtering from the surface and the steady temperatures provided by the surrounding ocean.

The difference of temperature between the air inside the biosphere, and the water outside it means the system does not even need fresh water, as evaporation from the ocean soon forms inside the spheres. Evaporation makes the water shed its salt, creating a ‘closed loop’ of hydration, doing away with the need for any kind of irrigation.

“Our garden is a self-sustainable system,” says Gamberini. “Indeed, once the crop system has been activated by an initial burst of fresh water obtained by desalination of seawater, it continues to sustain itself without any external support. We are growing tomatoes, beans and lettuce, all without the need for fresh water.”

This absence of irrigation is one of the key reasons why this approach to farming could help feed the world, particularly in climate change-impacted coastal drought zones. Gamberini says. “Traditional Agriculture uses 70% of freshwater worldwide, and water scarcity is increasing, making agriculture among the sectors most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.”

There are many challenges on the road to demonstrating how this can work commercially. He must continue to simplify the designs reducing the need for divers to plant, harvest and tend the plants, all of which add cost, time and complexity. Gamberini and his colleagues are still experimenting with the optimal size, shape and depth of the biospheres.

Storms are another hazard. Last year they damaged some of the biospheres, destroying their crops and forcing Gamberini to rethink the system he uses to secure them to the sea bed. Yet the venture still managed to grow multiple crops despite this, demonstrating how productive they are.

The data Gamberini is gathering seems to suggest that growing plants under the stronger pressures beneath the waves may speed their growth. “Preliminary evidences has shown us that higher pressure conditions affect the plants’ growth in a positive way which basically means a faster germination,” says Gamberini. “The limits of what can be grown are yet to be defined. Further researches will be addressed to understand the types of vegetables suitable for the underwater agriculture.”

“The project’s goal is to create an alternative system of agriculture, especially dedicated to those areas of the world where natural resources and harsh conditions make growing difficult.”

“There are huge opportunities if you make an early start,” he says. “One of the main things you need for a good AI strategy is data. As soon as you begin to collect the right type of data you are better placed for survival. It is better to be the disruptor than be disrupted.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions