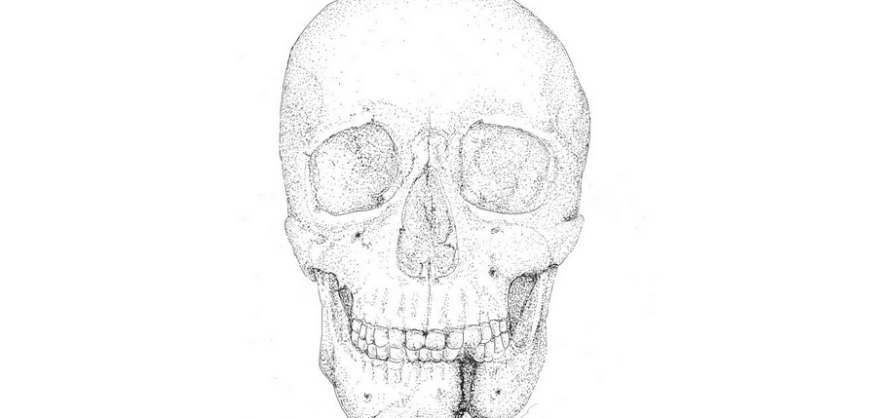

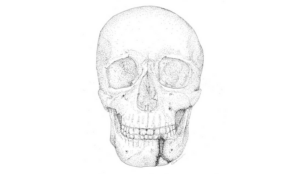

A rugged Byzantine warrior, who was decapitated following the Ottoman’s capture of his fort during the 14th century, had a jaw threaded with gold, a new study finds.

An analysis of the warrior’s lower jaw revealed that it had been badly fractured in a previous incident, but that a talented physician had used a wire — likely gold crafted — to tie his jaw back together until it healed.

“The jaw was shattered into two pieces,” said study author Anagnostis Agelarakis, an anthropology professor in the Department of History at Adelphi University in New York. The discovery of the nearly 650-year-old healed jaw is an amazing find because it shows the accuracy with which “the medical professional was able to put the two major fragments of the jaw together.”

(Image credit: Anagnostis P. Agelarakis)

What’s more, the medical professional appears to have followed advice laid out by the fifth-century B.C. Greek physician Hippocrates, who wrote a treatise covering jaw injuries about 1,800 years before the warrior was wounded.

Agelarakis and colleagues discovered the warrior’s skull and lower jaw at Polystylon fort, an archaeological site in Western Thrace, Greece, in 1991. When the warrior was alive in the 14th century, the Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was facing attacks from the Ottomans. Given that the warrior was beheaded, it’s likely that he fought until the Ottomans overcame Polystylon fort. In other words, it appears that “the fort did not surrender, but that it must have been taken by force,” Agelarakis wrote in the study.

(Image credit: Anagnostis P. Agelarakis)

Who were the Etruscans? DNA study might have solved the mystery

As the fort fell, the Ottomans likely captured and then decapitated the warrior; then, an unknown individual likely took the warrior’s head and stealthily buried it, probably without the “permission of the subjugators, given that the rest of the body was not recovered,” Agelarakis wrote in the study. But the warrior wasn’t given his own grave; his head was interred in the pre-existing grave of a 5-year-old child, who was buried in the center of a 20-plot cemetery at Polystylon fort. A broken ceramic vessel, which may have been used to dig the hole for the warrior’s head, was uncovered at the burial, Agelarakis added.

(Image credit: Anagnostis P. Agelarakis)

It’s unknown if there was any familial or other tie between the warrior and the child. Given that the man’s skull and jaw were found together, his head likely had soft tissues on it when it was buried in the mid-1380s, Agelarakis noted. The skull showed evidence of a “horrendous frontal impact,” which was inflicted around the time of the man’s death, he said.

Agelarakis detailed the unique burial in a study published in 2017 in the journal Byzantina Symmeikta. However, the study only briefly addressed the warrior’s healed jaw, so Agelarakis investigated that in detail, penning a second, new paper.

Read more: livescience